By Pam Tice, of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group

The full version of this article, with sources, is on the group’s website, here.

The story of the House of Mercy at West 86th Street and the Hudson River reflects the lives of young women in patriarchal mid-19th century New York, supported by the work of a devoted Episcopal woman who used her religious conviction and social skills to establish the home, and a group of Episcopal nuns whose formation was a historic moment for the church.

The Fallen Women of the 19th Century and the Efforts to Rescue Them

The House of Mercy was a home for fallen women. In the 19th century, the term “fallen women” applied to those who had transgressed current sexual norms, going back to the biblical fall in the Garden of Eden and the loss of innocence. “Fallen” was an umbrella term applied to a range of situations, including a woman having sex outside of marriage just once or habitually, a woman who was raped or sexually coerced by a male aggressor, a woman with a tarnished reputation, or a prostitute. For many women in mid-19th century New York City, prostitution was an economic decision.

As New York City began to grow in the 1830s, numerous organizations formed to take on the work of both reforming fallen women and preventing their fall in the first place. The New York Magdalen Benevolent Society, the Female Moral Reform Society, and the Catholic Church were the principal organizers.

The Charitable Christian Lady, Mrs. William Richmond

Sarah Adelaide Richmond founded the House of Mercy in 1855. She was the second wife of the Reverend William Richmond, the Rector of St. Michael’s Church, located at Amsterdam Avenue and 99th Street. While they were acquainted at St. Michael’s where Sarah served as the organist, they reconnected and married in Oregon. After Reverend Richmond lost his first wife to the New York cholera epidemic in 1849, he had left for the West Coast to help expand the Episcopal Church for the growing population. Mr. Richmond ended up in the Willamette Valley where he married Sarah in 1851. Sarah had gone west also seeking work as an educator. Making the trip west shows her adventuresome spirit — traveling to the West Coast wasn’t easy, including crossing Panama by mule, as the railroad wasn’t yet built.

Not long after their marriage, Mr. Richmond fell ill, and the couple decided to return to New York City.

Reverend Richmond resumed his leadership at St. Michael’s, where his pastoral duties included visiting the prisoners on Blackwell’s Island. Mrs. Richmond accompanied him, visiting the women in the female prison. She saw that a place was needed to support young women who showed some signs of wanting to change their lives.

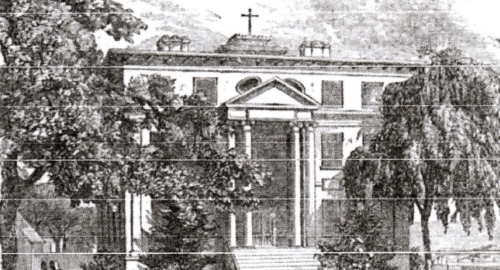

The assertiveness of Mrs. Richmond, along with her charitable nature, came into action at this point. She was able to make a career in one of the few areas open to women in the mid-19th century: charitable works. She chose the former Howland family mansion on West 86th Street, at the Hudson River, got a benefactor to pay the rent, established the House of Mercy, and then worked tirelessly to raise the funds to operate it and eventually purchase it. She described her charity as a home for homeless females under 20 years for both “those who have entered a vicious course of life and those who have not fallen but are in imminent peril.”

On a Friday evening In July 1858, tragedy struck the House of Mercy. Five young girls drowned when they were by the river trying to cool off. The housemother, Mrs. Knox, had given her permission and had someone watching them, but something happened and they struggled and sank. Small boats maneuvered to help them and soon the 22nd Precinct men showed up with grappling irons. The search to recover the bodies took much of the day on Saturday. Mid-day, a cannon, owned by Mr. Scarf of Striker’s Bay, was fired every 50 feet down to West 72nd Street as a way to bring a body to the surface, and this helped locate three bodies. A fourth surfaced later, but the fifth was never found. (Firing a cannon was a British superstition that found its way to the United States; it was thought that the firing would break the gall bladder of the corpse and cause the body to float. Both Edgar Allen Poe and Mark Twain used this mechanism in their writing. Thanks to the website straightdope.com for this.)

Mrs. Richmond is listed in the 1860 federal census as the head of the House of Mercy. The New York press praised her for her hard work and wrote of the House of Mercy as a protective place where young women “trembling on the brink of ruin” could learn sewing, housewifery, and horticulture.”

Mrs. Richmond became ill with cancer and continuing to manage the House of Mercy was proving difficult. Her son-in-law, Dr. Thomas McClure Peters, now the rector of St. Michael’s, sought help.

Episcopal Nuns take over the House of Mercy Management

In September 1863, five women arrived to take over the management of the House of Mercy. They had been part of a group of Sisters formed by the head of the newly established St. Luke’s Hospital but were unhappy there, so Dr. Peters suggested they come to the West Side. For the next 25 years, they operated the home on West 86th Street while they simultaneously formed their own organization. In February 1865, Bishop Potter established their formal monastic Sisterhood, the Sisters of St. Mary, the first such organization created by an Anglican bishop since the dissolution of the English monasteries in the 16th Century. While they were rejected as “Popish” by some Episcopalians, they were supported by others and soon had a school and children’s hospital in midtown, and a chapter house.

In 1870, the State of New York funded a new building at West 86th Street, expanding the House of Mercy. In 1878, the case of inmate Grace Hagar, who had been confined to the House of Mercy by two aunts who were unable to handle her behavior, began a time of less charitable accounts of what it was like in the Home. It was reported that girls were separated by the color of their dresses to distinguish between those who had an inclination to reform and those who had not yet done so. There was a room in the cellar where a girl could be held in solitary confinement and fed only bread and water. Also, the home’s operation was dependent on operating a laundry, considered job-training for the girls. New York State had stopped supporting denominational charities but the City of New York supported girls assigned to the House of Mercy by the courts.

In 1870, the State of New York funded a new building at West 86th Street, expanding the House of Mercy. In 1878, the case of inmate Grace Hagar, who had been confined to the House of Mercy by two aunts who were unable to handle her behavior, began a time of less charitable accounts of what it was like in the Home. It was reported that girls were separated by the color of their dresses to distinguish between those who had an inclination to reform and those who had not yet done so. There was a room in the cellar where a girl could be held in solitary confinement and fed only bread and water. Also, the home’s operation was dependent on operating a laundry, considered job-training for the girls. New York State had stopped supporting denominational charities but the City of New York supported girls assigned to the House of Mercy by the courts.

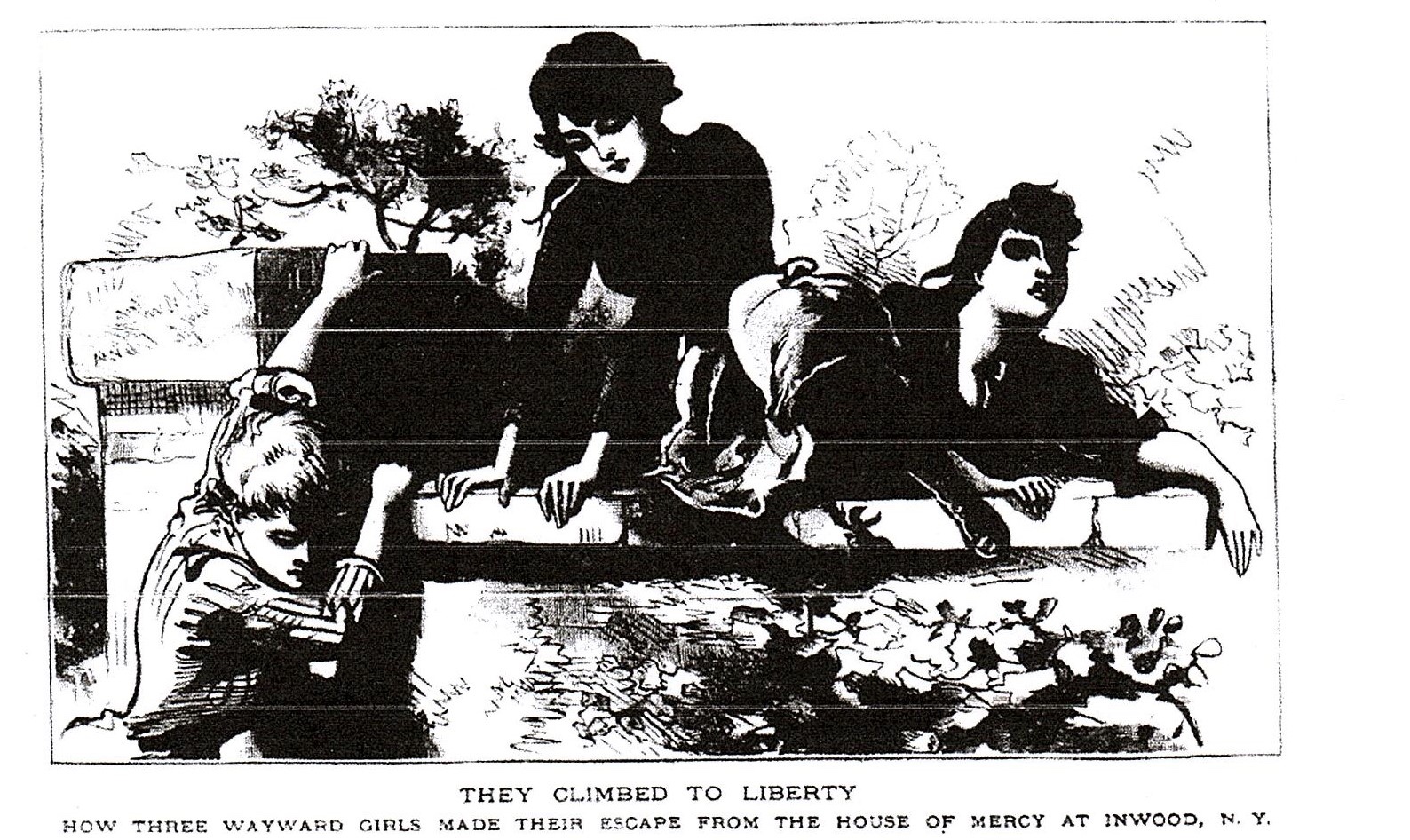

In 1889, the House of Mercy announced that it had been able to sell their site on West 86th Street for $225,000 and that this would fund a new building on land they purchased in Inwood. After the move to Inwood in 1891, the buildings were taken over by Miss Ely’s School for Girls, a private school for upper-class young women. Later, in 1906, the buildings were demolished when Miss Ely’s moved to Connecticut.

Meanwhile, up in Inwood, press accounts of mistreatment and unfair holding continued. Eventually, the House of Mercy was unable to raise sufficient funds and was closed down in the 1920s. The building fell into disrepair and was eventually demolished when Inwood Hill Park was developed.

Today, the Sisters of the Community of St. Mary is located in Greenwich, New York.

To receive WSR’s free email newsletter, click here.

I so appreciate your pieces of Upper West Side history! Thank you. However, your link to the full article is not correct. Here us a link that does connect with Pam Tice’s essay about “fallen women” and the House of Mercy on the UWS: https://www.upperwestsidehistory.org/blogs/neighborhood-charities-house-of-mercy

Thank you. Will fix.

This isn’t just the history of the UWS. It’s also the history of the mistreatment of women. I guess the whole thing starts with the ridiculous fairy tale of Eve ad the Apple, blaming women for a host of evils. In this historical recounting,, instead of finding and locking up the men who rapped women, society condemned women as “fallen”. Because many women had few economic prospects, they had no choice but to turn to prostitution in order to survive. They were condemned for it but not the men. It took a few hundred years to turn this around and there’s more work to be done as we have recently seen with the Me Too movement. Thankfully, back then there were caring people who worked hard and did what they could to help those in need in the only way that was available at the time.

Patriarchy will take centuries to undo. We need a woman mayor.

If a certain political party has its way, abandon’s the Constitution and establishes a theocracy not unlike Gilead, don’t be surprised if you see similar homes come into being.

“Patriarchal mid century New York” I had to laugh. While things have definitely. and thankful., Improved we still live in “patriarchal New York. Just sayin’ .

Hey, how’s about a story on the so-called Russian Spy House on West 86th St. near Riverside Drive?

That would be so interesting! Didn’t that building use to have a red canopy that said something like “Russian American Foundation” or Brotherhood??

It said “House of Free Russia,” as I recall! I always thought it was a place for anti-Soviet Russians to hang out, but what do I know?

That was it! Thank you. What do we know about them?

It was said of “laundry slaves” (women and girls confined to jails, prisons, reformatories, convents, etc.. , “Bad girls do the best sheets”.

Though quote above was said of laundries run by famous (or infamous if you will) Magdalene Sisters, all across Europe, North America and Australia from 18th through 19th centuries and well into 20th there were all sorts of institutions where confined women were put to work doing laundry.

By Victorian era if not earlier there was a strong association between “reform” of fallen women and laundry. Virtually all institutions both private and government run that were established to deal with “fallen women” put inmates to work doing laundry.

Laundry in those days was an orgy of back breaking and often dangerous manual labor. Arrival of steam and later electric powered laundry equipment lessened physical labor somewhat, but introduced more elements of danger.

https://archives.history.ac.uk/history-in-focus/Victorians/bartley.html

https://www.smh.com.au/national/bad-girls-do-the-best-sheets-20030424-gdgnfl.html