For twenty years, the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group (BNHG) has promoted research and education on the history of the Bloomingdale neighborhood of New York City’s Upper West Side. Bloomingdale is the name of the neighborhood from West 96th to West 110th Street, between Central Park and Riverside Drive. This area has been referred to as “Bloomingdale” for over 300 years.

This is the second part of an article written in May 2020 by Pam Tice, a member of the BNHG. The first part appeared yesterday, and you can read it here. The sources used to write the article are printed at the end of this post.

You can read all of WSR’s Weekend History posts here.

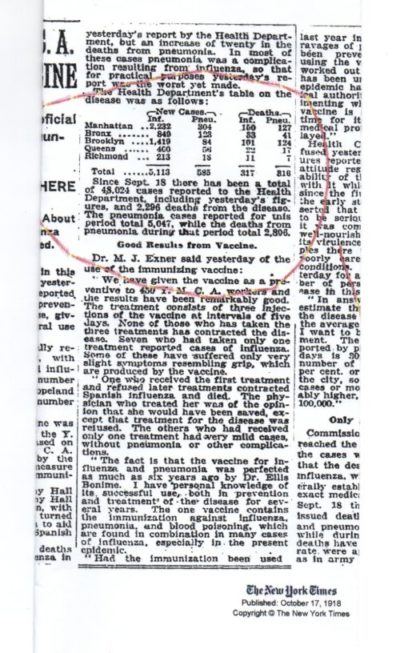

There were daily newspaper reports, by borough, of new cases of flu and pneumonia. By October 5, 1918, the Surgeon General was calling for New York City to close its schools, churches and theaters, but [Health Commissioner Royal S.] Copeland was still insisting that we were not stricken in the same way as Boston; he also said that half of the 1,600 cases that day “were in 600 families.” However, that day the Health Department issued new rules that asked stores, offices, textile manufacturers and “other manufacturers” to stagger their hours so that crowding on the subway could be lessened. Copeland’s solution seemed to be to “keep calm, and go about your business.”

As often happens during a crisis, multiple events take place. For New Yorkers, that happened on October 6 when the T.A. Gillespie munitions-loading plant near South Amboy, New Jersey, blew up in a succession of explosions, causing buildings all over Manhattan to tremble, and all the bridges and “tubes” closed in fear that they would be compromised. Hundreds died, and nurses and doctors rushed to the scene.

The next day, the reported flu cases increased to over 2,000. Copeland set up a “Hospital Clearing House” to assign patients to one of the city’s hospitals, and asking the private hospitals to suspend all elective surgeries. Medical students who were nearly finished with their training were released from their universities to help. Many doctors and nurses were called upon to help at the explosion site in New Jersey, leaving the city’s facilities badly understaffed. The war had also taken many doctors and nurses away, with estimates as high as 30% of the City’s medical workers serving in the military and the Red Cross.

In 1918, nursing care was the primary treatment for the flu. There were no antiviral medications, although during much of the autumn, the Commissioner kept mentioning that a vaccination might be happening soon. Nurses kept a patient warm, nourished with chicken soup, and with bed linen kept clean. If there were signs of pneumonia, a “pneumonia jacket” might be used; this was another warming technique—some had coils of rubber tubing arranged to cover the chest that circulated hot water.

Lillian Wald had started what became the Visiting Nurse Service down on Henry Street in 1893. She was well-regarded for her work in public health, and so Copeland consulted her in forming the New York City Nurses Emergency Council in early October as a way to coordinate trained nurses and volunteers with experience in care for the sick to help them. All the nurses who worked in the various bureaus of the Health Department, such as those assigned to schools, became part of this effort.

To this cadre of women was added the Women’s Motor Corps, an organization formed for war work, but now asked to drive nurses and assistants around a neighborhood, stopping to see those who had requested nursing help. Women supplied their own cars—many women with access to cars were driving electric cars that did not need hand-cranking. They were supplied with linens, soup, and pneumonia jackets to take care of the sick. They were also expected to help with the household if a woman was a patient, making sure the children were tended to. Trained nurses were accompanied by volunteers, women who had some experience in care of the ill, who could help the nurse with more mundane tasks.

Women’s Motor Corps in New York City

On October 10, the Department of Health set up a city-wide “influenza clearing house” in 150 neighborhoods, to provide a place to go to ask for help with nursing a patient at home. In Bloomingdale, this was at the Bloomingdale Clinic, part of the outreach program at St. Michael’s Church, at 225 West 99th Street. There were also outreach centers established at Bretton Hall on Broadway at 86th Street, at the neighborhood house of the Free Synagogue on West 68th Street, and at the Young Women’s Hebrew Association on West 110th Street.

By October 17th, the reported number of flu cases was over 10,000. However, based on the death rate, Copeland said that he thought only 50% of the cases were being reported. Undertakers were now experiencing problems handling the deceased. Florists were unable to fulfill orders.

The Department of Health issued orders to arrest landlords who did not supply sufficient heat with the wartime limits on fuel lifted.

The Mayor and Copeland attacked private physicians with “profiteering” by overcharging. The private physicians shot back that the publicly-paid physicians made no effort to arrest the disease when it came to New York. Rabbi Stephen Wise gave a speech at Carnegie Hall that the Department of Health had become less skilled and effective. This open criticism was matched by conspiracy theories such as the fact that German spies had come to the city “via submarine” and had released the flu in a crowded movie theater.

The peak day on the epidemic curve seems to have been October 20. The New York Times reported on October 22 that there had been 37,025 cases of the flu and 4,332 cases of pneumonia in the preceding week, October 14-21. Deaths from the two were 5,372 that week.

A few stories of difficulties with undertakers emerged in the newspapers. One was labeled “coffin fraud” when two undertakers were accused of receiving bodies of soldiers who had died in the training camps and placed in coffins with a government stamp, of removing the stamp and reselling the coffin. In what may have been a typical story, the newspaper reported a “West Side family” contracted for $60 with an undertaker to handle a burial. When the time came for the funeral, the undertaker told them the charge would be $150; when the family sought another undertaker, the first one refused to release the death certificate. The Health Department answered their appeal, turning the undertaker over to the District Attorney. The newspapers reported that, in general, coffins were scarce, and profiteering and extortion were common.

One undertaker in Bloomingdale was at 68 West 106th Street. There may have been others. Poor people and those of modest income may have held funerals at home or in a local church with the undertaker removing the body for burial. For middle and upper class New Yorkers on the Westside, the Frank E. Campbell “Funeral Church” building on Broadway between 66th and 67th Streets was the place to go.

In a newspaper listing of deaths on October 27, 1918, there were 109; for the same day in 1917, there were 45. Not all deaths were attributed to the flu or pneumonia, but the deceased’s age, in the 30s and 40s, or the use of the word “suddenly” gave a hint of the reason for the death.

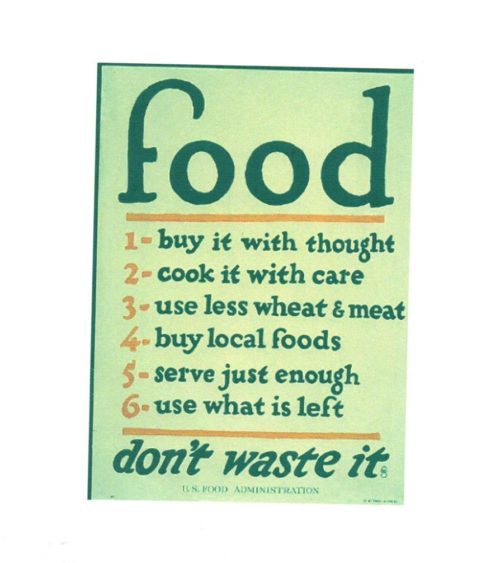

While the flu epidemic was expanding across the City, our Bloomingdale neighbors were also coping with the demands of their lives caused by the U.S. entry in April, 1917, to World War I. War demands were often about changing behavior. In the spring of 1918, “American Wheat Wasters,” people living on West 76th and 77th Streets, were severely criticized for their alarming indifference to food conservation. The Department of Health accompanied garbage wagons along these streets and actually counted and weighed the food waste, criticizing the people who lived there, described as “sufficiently well-to-do so as to have the services of two to six servants”. A cook commented that the family she cooked for did not eat toast that had gotten cold.

In the Spring of 1918, the second enrollment for the draft was called. Bloomingdale’s Local Draft Board 134 was at 2875 Broadway. The New York Times printed 500 names of those selected that day, including Board 134’s selections, and they left for Camp Upton a few days later. Rafael Albert, 331 West 101; Isidore Rosenblum, 160 Manhattan Avenue; William Kuhn, 972 Amsterdam Avenue; and Jack Carlos, 230 West 107th Street were chosen.

For young women, the war created opportunities. The trolley cars recruited women to be conductors. At the West Side Y.M.C.A. there was an auto school to train women as drivers and mechanics. The Westinghouse Lamp Company on 512 West 23rd Street, a clean, well-lit factory, with fresh air, advertised for girls at 20 cents an hour with a 10-cent increase in two weeks.

The Red Cross was very active, leading the effort to organize knitters, collecting donations, even organizing a big parade as a way to demonstrate patriotism. There was a big knitting event on the Central Park Mall.

Some Bloomingdale lives may have been upturned in early September 1918 when a day-long “hunt for slackers” took place all over the city under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Justice. Young men were stopped on the street, and, if they could not produce a draft card, they were first taken to the local police station—in Bloomingdale, the 32th Precinct on the south side of 100th Street—and then put into automobiles and driven to the Armory on 25th Street where they were signed-up. Over 20,000 agents fanned out over the city that day.

On September 1, The New York Times announced that the third draft would be held on September 12. Draft Board 134’s registration site that day was at PS 165 on West 108th Street. Police and firemen were generally exempt, along with men in “war work” jobs.

Simultaneously, the newspapers were printing lists of soldiers and sailors killed in the War, printing the exact address for the New Yorkers. Typically, the listing showed a summary of the number who died, and the reason, as “in battle,” or “of wounds,” or “injured,” and then the actual names by service rank. Maurice Longstreet, a young man who worked as a butcher on Columbus Avenue, was severely wounded on August 17, 1918, but recovered, and was discharged in February 1919. He appeared in the 1920 census, living on West 106th Street. The October 4 report printed in The New York Times announced that Pvt. Fletcher Battle, 72 West 99th Street was killed and Corporal M. A. Lynch of 107 West 98th Street was severely wounded.

Mrs. Merriles on West 107th was written about in a separate article. Her son, Charles, was killed in an explosion in an ammunition shop and a foster son, Leslie, was killed in action in France. Two other sons were in the Navy.

Another concern in Bloomingdale, site of the Lion Brewery on Columbus Avenue, would have been the September 7 story in the Times that all the nation’s breweries would have to be closed down by December 1. The Fuel and Food Administration would be cutting off supplies of grain and fuel to conserve materials needed to win the war. One observer imagined that beer would be an obsolete drink six to eight weeks after the breweries closed. We have to assume that this action was not implemented but, of course, it would not be long before Prohibition happened, and the brewery was affected.

Another neighborhood activity in October 1918 was voter registration. The newspapers printed lists of where to go to register. Several churches in the neighborhood were listed: Grace Church on West 104th, St. Michael’s on West 99th Street, and the Presbyterian Church at 105th Street and Amsterdam. Registration was also at the Home for Aged Hebrews, on West 105th Street and the Half-Orphan Asylum on Manhattan Avenue. The neighborhood schools were also sites.

Election Day was November 5, the first in New York State when women were able to vote. The State Constitution had been amended in 1917 to grant women suffrage; the U.S. Constitution was still waiting to be amended in 1919. In Bloomingdale, the polling places, listed by Election District, were numerous: barbershops, laundries, tailors, and shoe stores along Columbus Avenue, perhaps reflecting that men were more comfortable in these places of business. PS 179 was also used. Mary Garrett Hay of West 112th Street, New York Suffragist and good friend to Carrie Chapman Catt, was quoted: “It seemed as natural as breathing, and I felt as though I had always voted.”

The number of new flu and pneumonia cases dropped during November and December, but grew again the first seven weeks of 1919. It also came back in the winter of 1920 but Commissioner Copeland declared it to be of a milder version. However, in 1918 the excitement of the war ending, on November 11, and then the parades celebrating the Armistice dominated the news more than flu stories, leaving families to deal with the illness on their own. The Women’s Motor Corps operated in the winter of 1919.

One especially heartbreaking effect of the widespread illness, particularly its effect on young adults, was the number of orphaned children created by the epidemic. Jewish families, in particular, were appealed to, to take in orphans. Perhaps of use in the Bloomingdale neighborhood was the Manhattanville Day Nursery, an emergency shelter for babies where “forelorn fathers” who could afford the $5 weekly boarding fee would send their infant children if the mother was ill. Other infant-care institutions that sought private homes where an infant could be cared for, as it was recognized that private home care was better for the child. The Department of Health counted 650 babies that it helped during the time of the epidemic.

On November 17, 1918, Commissioner Copeland was interviewed by The New York Times and gave himself high praise for remaining calm, preventing panic, and allowing the city to “go about its business.” While he was still Health Commissioner in 1923, Copeland was elected to the U.S. Senate, and served until his death in 1938.

After the data for the 1918 flu epidemic was sorted out, New York came in with a lower “excess death rate per 1,000”, reporting 4.7 compared to Boston at 6.5 or Philadelphia at 7.3. Public health historians gave the city credit for its disease management techniques. Newspapers also compared the deaths from the war to the deaths from the flu epidemic, noting the alarming numbers for the epidemic.

One of the impacts of the epidemic may have been in the numbers of fairly young widows and widowers observed in the 1920 federal census for Bloomingdale. The census district pages show about one-third more, especially adults in their 30s and 40s, compared to a similar district in 1910. The war, of course, may have added to the numbers.

As I finish writing this piece [in mid-May 2020], the deaths in New York City from our 2020 Pandemic have reached over 20,000 and are still climbing. Local historians have begun working on how we will document and remember this time.

Sources

Aimone, Francesco, “The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in New York City: A Review of the Public Health Response” Public Health Reports (1974-) Volume 125, Supplement 3, April 2010, pp 71-79. (downloaded March 14, 2020)

Federal Census data at www.ancestry.com

Gladwell, Malcolm “The Deadliest Virus Ever Known” The New Yorker September 22, 1997. Accessed online, March 2020

Keeling, Arlene W., “Alert to the Necessities of the Emergency: U.S. Nursing During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic” U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Public Health Reports. Accessed online on April 20, 2020

New York City Department of Health, Annual Report 1918. Available at: www.tlcarchive.org (The Living City Archive at the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University)

Newspaper articles from The New York Times online archive, newspapers accessible online at GenealogyBank. com, and newspapers at the Chronicling America collection at the Library of Congress (The New York Tribune, The Evening World, The New York Herald, The Sun, The New York Daily Tribune)

Olson, Donald R., Lone Simonsen, Paul J. Edelson, Stephen S. Morse and Edwin D. Kilbourne, “Epidemiological Evidence of an Early Wave of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New York City” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States of America Vol 102, No. 31 (August 2, 2005) pp 11059-11063 (downloaded March 29, 2020)

Stern, Alexandra Mina, Mary Beth Reilly, Martin S. Cetron and Howard Markel, “Better Off In School: School Medicine Inspection as a Public Health Strategy During the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic in the United States,” Public Health Reports (1974-) Volume 125, Supplement 3, April 2010, pp 63-70. (downloaded March 26, 2020)

Wallace, Mike, Greater Gotham: A History of New York City, 1898-1919, Oxford University Press, New York, 2017

“Women of the Red Cross Motor Corps in World War I” available online at the website of the National Women’s History Museum.

these missives from the past are terrific; thank you!

So less denial and dismissal from the City than in 2020, and more better organization through out the epidemic.

Where is Dr. Copeland when you need him? The sick were quarantined, given compassionate and effective care and the healthy were encouraged to carry on. Instead we got mass hysteria, quarantine of the healthy, unemployment, ruined businesses and a huge spike in suicide, overdose, domestic violence and other devastating consequences.

“This area has been referred to as “Bloomingdale” for over 300 years.”

This is not accurate. According to the Encyclopedia of New York, the key issue is the name Bloomingdale Road: Early Road, the precursor of Broadway. Opened in 1703, it ran from what is now 23rd Street to the northern end of Bloomingdale village, today’s 114th Street. In 1795 the road was extended north to 147th street and linked to the old Kingsbridge Road. In 1869 the Western Boulevard was built over the Bloomingdale Road north of 59th Street. Known popularly as The Boulevard, in 1899 “Broadway” was formally applied to the entire route from South Ferry through Manhattan’s northern tip and to the boundary between the Bronx and Yonkers. Broadway between 59th and 168th streets retains its 150-foot (46-meter) width and wide median as legacies from The Boulevard. In the vicinity of 125th street east of Broadway, a short street (Old Broadway) today follows the original Bloomingdale Road.

Most of “Bloomingdale,” as your writers describe, has little to do with the Upper West Side, but rather is a much larger swath of the island. In fact it wasn’t until about 15 to 20 years ago that anyone would use the word particularly for the area between 96th and 110th along Broadway. It is important not to romanticize too much.

Yes, the reader is right — Bloomingdale once referred to a large area of the west side of Manhattan. Eventually, in the 19th century, it came to refer to an area around 100th Street, part of the larger area, as “Bloomingdale Village.” It is that named area that we draw upon today to name our neighborhood.

Thank you, yes, I recall reading at one point that when the area really got settled and various institutions established themselves here, the name fell out of favor, partly because of the insane asylum and the new cancer hospital. Land owners didn’t want to be associated with the name. Also when I was growing up, no one I knew called it Bloomingdale, and that name didn’t appear on current maps before about 1990, or so. Perhaps that is because of your group’s looking into the history?

Very interesting article. I recently obtained a large collection of letters written between my paternal grandparents between 1917 and early 1919. They were newlyweds, living in UWS NYC (west 96th St), and much of their correspondence, apart from the constant “I miss you” cries from both, addressed the “flue” as they wrote it early in this correspondence. My grandmother was pregnant with my father, and running a family business downtown in (current) financial district while my grandfather was out in the midwest selling for that company, making sales calls and travelling the midwest by train. Both were concerned for the health of the other, and discussed family and friends in both areas who had gotten sick. Amazing insight into how everyday people dealt with the anxiety of the necessity to keep going on with life with illness surrounding them.