For twenty years, the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group (BNHG) has promoted research and education on the history of the Bloomingdale neighborhood of New York City’s Upper West Side. Bloomingdale is the name of the neighborhood from West 96th to West 110th Street, between Central Park and Riverside Drive. This area has been referred to as “Bloomingdale” for over 300 years.

This article was written in May 2020 by Pam Tice, a member of the BNHG. Due to its length, it was divided into two posts. The second will appear tomorrow, Sunday, October 10th. The sources used to write the article will be printed at the end of tomorrow’s post.

You can read all of WSR’s Weekend History posts here.

I had a little bird, Its name was Enza, I opened the window, And in-flu-enza.

~ Children’s Rhyme, 1918

Mid-May 2020 ~ As our 2020 Pandemic Spring unrolled over the past few months, there have been numerous articles reaching back to 1918 when the “Spanish Flu Epidemic” spread across the United States. On the 100th anniversary in 2018, historians looked back on that time, most not imagining that we would be re-living this type of historic event just two years later. As I get ready to upload this post in mid-May 2020, New York’s City’s 20,000 + deaths from the Covid-19 virus are close to matching the number of deaths in the fall of 1918.

Back in March [2020] when New York went on “pause,” I decided to learn about the 1918 flu epidemic in New York City, and then learn how the illness may have played out in the Bloomingdale neighborhood on the Upper West Side. I wanted to understand what local life would have been like at that time.

I started with the articles about 1918, focusing particularly on New York City. I looked in the academic journals, and searched the newspapers. My search was all online, of course, as all archives are currently closed. I read all the contemporary pieces where the historians discuss 1918 in light of today’s ongoing event. Nothing I found (almost) related directly to Bloomingdale. Nevertheless, I learned a lot about New York City in 1918. I decided to share what I’ve learned—about the flu epidemic, about the public health and the nursing profession, and about World War l in New York City—and how all of these things might have touched the lives of those living in Bloomingdale.

Many who have written about the 1918 flu epidemic—no one called it a “pandemic” then—note how it was barely even remembered. The disease killed 33,000 in New York City when our population was 5.6 million. In the second wave of the disease, the fall of 1918, more than 20,000 New Yorkers died. In the United States, 675,000 died. There are a few written memorials, but, in general, everyone simply moved on after it was over. In his novel “The Plague,” Albert Camus describes the many millions of bodies as no more than an intangible mist drifting through the mind. Many of us today find evidence of the 1918 flu as we research family history, stories of the long-time grief experienced when parents and siblings were lost to the epidemic. The stories aren’t always sad: a recent comment to a New York Times article tells the story of a grandmother telling of the time she woke up in the hospital in 1918, heard the bells of Armistice Day ringing, and thought she’d gone to heaven!

1918 in New York City had kicked off with a new Mayor, John F. Hylan, supported by the Democratic machine. He replaced John Purroy Mitchel, whose progressive ideals were reflected in the City’s Health Department with its work in combatting tuberculosis and other communicable diseases. In the Spring of 1918, Hylan’s first Commissioner of Health had tried to cut back the expenses of the Department and created an outcry from the public reflected in news reports. By May, 1918, a new Commissioner, Dr. Royal S. Copeland, was appointed and assurances made that the medical community and the City would work together. Commissioner Copeland was in the news nearly every day as the epidemic became apparent late in the summer.

Later, medical historians would analyze the Department’s data and conclude that February to April 1918 was the first wave of the pandemic in New York City. Medical historians saw the beginning of the U.S. epidemic at Camp Funston, part of Fort Riley in Kansas, where U.S. Army recruits suffered thousands of losses among the troops preparing to go to Europe. By summer, the flu was raging at the east coast military facilities. The disease’s arrival may have been under-reported as such news was felt to undermine our military strength. However, Spain was neutral in the War, and the flu there was publicly reported. This led to its name, the “Spanish Flu.”

It wasn’t until the second wave of the virus began on August 14th that New York City’s Health Department required that physicians report flu and pneumonia cases. Medical historians pinpoint the New York City epidemic when the Norwegian vessel Bergensfiord arrived with ten people ill (two had died at sea) and all of the sick were taken to Brooklyn’s Norwegian Hospital. Typically, at that time, vessels were quarantined at the Swinburne and Hoffman Islands off South Beach on Staten Island. At this point, the disease was often still referred to as “the grippe,” the name given during the earlier epidemic in 1889-1891. On August 15th, the Health Commissioner declared that there was “not the slightest chance of a Spanish Flu epidemic here.” By August 20th, he was describing the influenza “of a mild form” and declaring there was “no cause for alarm.”

On August 20th, The New York Tribune published a list of dos and don’ts for treatment of the flu:

- Don’t use a common towel at home

- Avoid contact with anyone sneezing or coughing

- Don’t expectorate (spit)

- Burn or boil the bedclothes of anyone who is sick in your home

- Ventilate your home and workplace

- Avoid dry-sweeping that raises dust.

By late August and into early September, the news of cases if the flu and the accompanying pneumonia at military camps in New England: Camp Devens near Boston, and the naval forces in New London, Connecticut. For New Yorkers, many recruits were at Camp Upton at Yaphank, Long Island. Families in the City were allowed to visit the Camp. Soon the flu was spreading there.

Meanwhile, Copeland was still reporting that the cases in New York City were all from those coming here on ships. On September 19, The New York Times reported that three cases of the flu on Central Park West were home-grown, not from any ship’s arrival. Now the City had two jobs: isolate the sick, and prevent the disease from spreading in the healthy population.

How did the Department of Health’s new rules and warnings affect our Bloomingdale neighborhood?

First, in an early ruling on September 19th, the Commissioner said that anyone in a house or apartment who caught the flu could stay at home, in strict quarantine. There was no way to monitor this, however, except through a family physician. Those who lived in tenements or boarding houses would be removed to a city hospital.

At this time, there was just one city hospital in each borough, but Manhattan had two: Bellevue Hospital and the Willard Parker on West 16th Street. Over the next few weeks, the City scrambled to add beds in each hospital as well as develop new beds, such as re-working the Municipal Lodging House down on 25th Street as a place to care for those ill with the flu. The hospital ship The Riverside was brought to the East River near the Willard Parker hospital to add beds. During the height of the crisis, the Health Commissioner admitted that the city’s hospitals were crowded, and that there was no room for women patients.

The City’s private hospitals were no doubt flooded with patients also: the Park Hospital on Central Park West at 99th Street, and St. Luke’s up on West 114th Street, to name those nearest to Bloomingdale. The Park Hospital had only 64 beds. It was originally developed by the Red Cross as a teaching hospital for nurses, and re-named the Park Hospital in 1915 when the Red Cross decided to no longer operate hospitals.

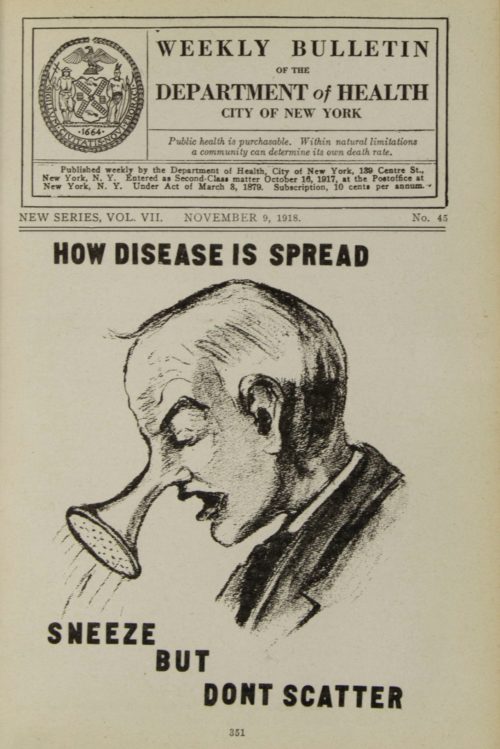

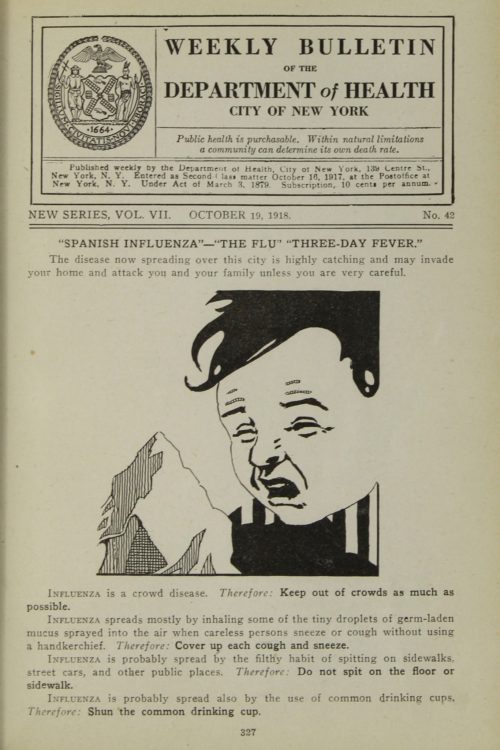

Copeland was particularly worried about the potential spreading of the virus on the transportation system: the subways, trolleys, ferries and trains. He had 10,000 placards printed, spreading them throughout the system. They warned “To prevent the spread of Spanish influenza, sneeze, cough or expectorate (if you must) in your handkerchief. You are in no danger if everyone heeds this warning.” Our Bloomingdale neighbors would have seen this placard on the elevated train along Columbus Avenue, the trolley cars on Central Park West, and the subway running under Broadway. The posters were also in store windows, at the police precinct on West 100th Street, and other public places.

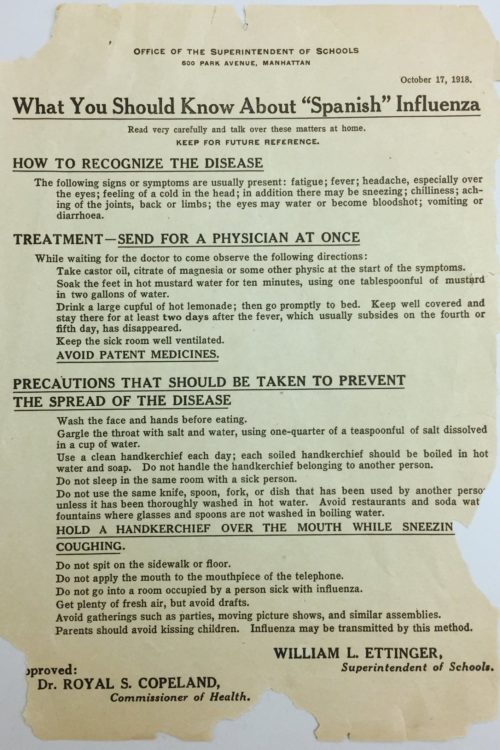

Here are a few additional images of printed material:

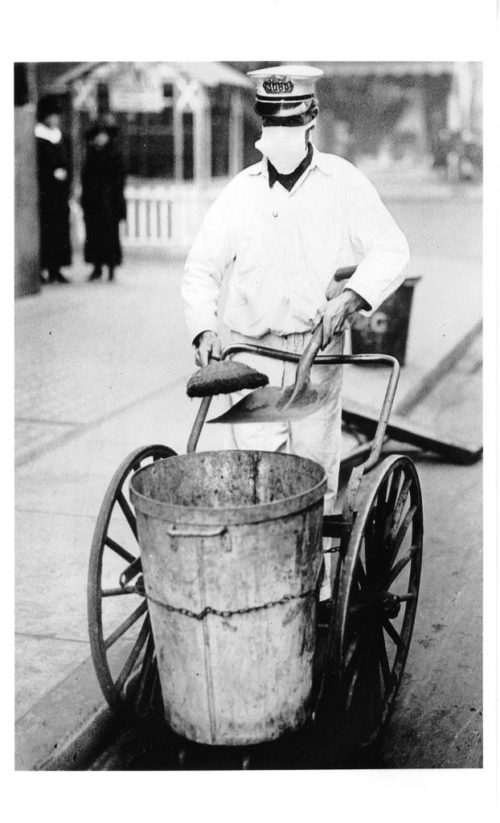

The City started an anti-spitting campaign 20 years earlier; the Sanitary Police reinforced it in 1918. Even the Boy Scouts got involved, handing out cards to anyone seen spitting, reminding them it was illegal. The newspapers reported cases of spitting arrests, and fines were imposed.

Another area of concern was the popular movie theaters. Copeland declared that the large well-ventilated theaters could be kept open so long as no more than two rows of standees were allowed in the back, and no smoking was allowed. He also saw the theaters as a way to communicate his messages about using a handkerchief if you sneezed or coughed. Copeland also saw that he might cause panic if people saw their beloved movie theaters closed. He did appear to be against the “dirty, stuffy, hole-in-the-wall” small, unventilated theaters, and threatened to close them. In Bloomingdale, there were two that may have been small and stuffy. There was the Park West on West 99th Street near the Fire Department Training School and The Rose on West 102nd Street next to the Post Office, on the same block as PS 179.

The “movie palaces” on Broadway at 96th Street, the Riviera and the Riverside, stayed open. The “Shubert-Riviera” advertised on October 2nd that the film “The Very Idea” would be showing, with orchestra seats for the evening show at $1. There were other larger movie theaters in the neighborhood.

Copeland also warned about using shared cups and utensils. Drinking fountains in city parks had cups hanging on them. Soda fountains were targeted as they often did not wash drinking cups and food utensils between users. Like the people caught spitting, soda fountain operators were brought to court and fined, with their names printed in the news.

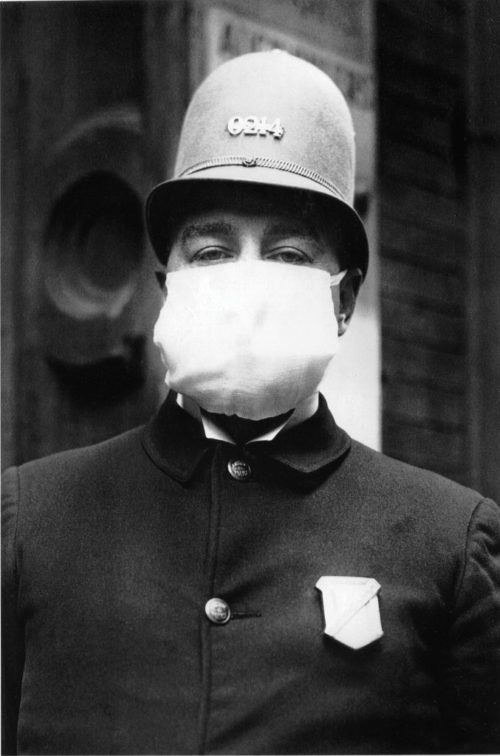

Wearing a gauze mask became common, first by hospital workers, and then by others. The most-often printed photos of the 1918 flu show a New York City postal worker, a sanitation worker, and a police officer wearing masks. The photo of young women working has been shared a lot too.

By early October, the cases of the flu and pneumonia were mounting fast. There was great pressure on the Commissioner to close the schools, although it was not clear until later that children were not particularly targeted by this disease. Young adults 20 to 45 were more likely to get sick. Later, after the data collected was analyzed it was generally thought that older people, in their sixties and older, had some protection from the 1889-91 epidemic they had lived though.

Since 1897, the schools were part of the City’s disease prevention system. In 1908, Dr. S. Josephine Baker, a leading expert in public health, had taken over the Department of Health’s Child Hygiene Bureau, leading 192 medical inspectors and 195 nurses who worked in the schools to check for signs of illness. In Bloomingdale, PS 54 at 104th Street, PS 165 on West 108-109th Streets, and PS 179 on West 102-103rd Streets would have been part of the system.

In October and November 1918, children were directed to report directly to their classroom in the morning with no loitering in the schoolyard. Teachers looked for signs of the flu, and, if found, the medical inspector took over and made sure the child went home and was seen by a family physician or public health doctor.

Dr. Copeland and Dr. Baker thought that this system of daily inspection was far better than letting all the children stay at home. They were also able to send flyers home with the children on how to handle family members who caught the flu. Public Health and education about disease was so important at this time that the American Museum of Natural History had a “Public Health Hall” where exhibits visited by many New York schoolchildren added to their classroom work.

Private schools may have had a different outlook. A newspaper reported that Dr. Copeland’s son caught the flu and his school, Ethical Culture, was closed.

Tomorrow, Part II.

When I was a child there were lots of people around who would have remembered the Spanish Flu. But I don’t remember any real discussions about that pandemic. What I seem to remember is that if a lot of people were sick in the winter an older person might might say, “Maybe it is the Spanish Flu”? But this was followed by silence. No one ever agreed or disagreed.

“Dr. Copeland and Dr. Baker thought that this system of daily inspection was far better than letting all the children stay at home.”

Such a shame that this city and our UWS community, still remains silent on this issue. Meanwhile, public school children are majorly affected by unnecessary school closures and arbitrary union rules for political gain. These children are devoid of a normal school life, almost 2 years later while the adults of this community sit idly by. We can look to the past for wisdom.

Re: “…arbitrary union rules for political gain.”

1. The UFT’s leadership is elected by members to protect BOTH their fiscal AND physical well-being. As union president Mr. Mulgrew is doing what his members expect. He speaks FOR them and is responsible TO them; so where is the “political gain”?

2. Mr. Mulgrew does NOT act alone; he is also responsible to the UFT Delegate Assembly: a body of teachers elected by their city-wide colleagues to advise union leadership on matters of concern.

And therein lies the rub….

The UFT protects THEM: the teachers, not the students. The Principals and Superintendents have their own unions too.

The only advocate for the students are the parents. Why aren’t more parents taking control in NYC? There are groups already formed for this purpose.

Charles – thank you! We’ve mobilized, we’ve raised money, we’ve sued, we’ve taken it to Twitter, we’ve talked to journalists, media/press (we’ve reached out to WSR on multiple occasions to set the record straight – no dice in our favor), we’ve advocated (and continue to do so). We continue to do everything that we can, but we keep asking ourselves that same question. The gaslighting of parents is out of control, and this community (and the greater population across NYC) remain silent and disengaged. All the while, kids only have us to advocate for them. But they are an afterthought in this country and in this state. And it shows.