Central Park Conservancy historian Marie Warsh, who has done research into Seneca Village.

By Michael McDowell

In advance of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Central Park Conservancy historian Marie Warsh led the West Side Rag and colleagues from New York Amsterdam News on a tour of what was once one of New York’s first communities of black property owners: Seneca Village, on the west side of present day Central Park, between 82nd and 86th Streets.

Conservancy guides will debut an updated Seneca Village tour on MLK Jr. Day; more information and tickets are available here, and additional dates are scheduled throughout the year. The Conservancy has been collaborating on the project with the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History.

(Update: Monday’s tour was cancelled due to weather.)

Seneca Village was first settled in the 1820s, in part due to the 1821 New York Constitutional Convention. State Democrats, led by future president Martin Van Buren, successfully amended the state constitution to abolish a property qualification barrier to voting for all white men, while increasing the amount of such a qualification for black men. This incentivized free African-Americans to purchase property, some of whom did so in Seneca Village.

At the time, black leaders were also considering how to create their own institutions, their own spaces, and their own neighborhoods in a concerted effort to build places of refuge from racial violence, as well as to found autonomous communities, according to Warsh.

The first property owners to move into the area acquired land in the early 1820s, and the village grew in the 1830s and 1840s. By 1855, when the urban portion of New York City extended only as far north as 23rd Street, Seneca Village was a vibrant middle-class suburb of 225 residents, half of whom owned their homes. While some of these were modest, others were more luxurious two-story frame houses, with space for gardens, and perhaps even a barn or stable. A nearby spring beneath Summit Rock, the highest point in Central Park—from which the Hudson is visible—served as a water source, and spiritual needs were fulfilled by three churches: AME Zion, African Union, and All Angels. Children were educated at Colored School No. 3, which was a member of the then-segregated public school system.

In her research, Warsh said she has only uncovered the name ‘Seneca Village’ in a single contemporaneous document—the notes of the pastor of All Angels Church—and it’s unclear if that was the name used by those who lived in the community. In other documents, the town is denoted as ‘Yorkville’, which most readers would associate with a neighborhood on the Upper East Side.

Nomenclature aside, Seneca Village was the most densely populated piece of Central Park, and one can imagine that the pastoral setting near the river provided a welcome respite from the squalor and disease of lower Manhattan.

Such a sentiment would not be unfamiliar to modern day Upper West Side residents.

Efforts to interpret Seneca Village are ongoing, Warsh emphasized. An archeological survey was conducted in 2011, and unearthed items including a child’s shoe, an iron tea kettle, a fragment of a Chinese porcelain vessel, and even the handle of a bone toothbrush—further evidence of the community’s prosperity, despite previous depictions of Seneca Village as a shanty town populated by squatters. In all, thousands of artifacts were found on the site; these have been stored at the New York City Archaeological Repository.

The tour passes the sites of each of Seneca Village’s three churches. Near one of these, a stone foundation is visible, but the stones date only from the 1930s and are actually the remnants of a large sandbox.

Seneca Village occupied what is now a beautiful slice of the park: rocky, with rolling topography, scattered trees, and sweeping views. Seeing the site today, it is fascinating to imagine the once-upon-a-time diverse and prosperous community — two-thirds African-American, one-third Irish — all still far from the growing city. The Irish had arrived in the 1840s, along with a few German immigrants.

Surnames on property documents include Doremuss, Dashwood, Quinn, Mingo, Riddle, and Hampton. The main street of Seneca Village was known as Spring Street, which ran into Stillwells Lane. One can picture wooden homes, with smoke rising from sensible chimneys, surrounded by orderly gardens, and hear the conversation of families, the neighing of horses, all of it set in the midst of farm and forest.

But the Seneca Village story ends in 1856-1857, when the community was razed to make way for the construction of Central Park.

“In planning for the creation of the park, the city used eminent domain to displace the community of Seneca Village as well as the approximately 1,400 New Yorkers living on the land designated for the park,” Warsh said. “Research is underway to trace where residents relocated, and even to find descendants.”

Warsh found evidence that remains in the Seneca Village cemetery were moved and reinterred—in Cypress Hills, Queens, among other areas—prior to the town’s demolition, but she has not found evidence that the community remained intact.

Evidence suggests instead that some residents relocated to Queens, others moved further uptown, a few departed for different cities altogether. Seneca Village residents do not appear to have moved to Weeksville, Brooklyn, a historical community of free African-Americans in what is now Crown Heights.

There is also the presumptive loss of the valuable land seized via eminent domain: were African-American property owners compensated equitably? It isn’t clear, Warsh said.

While it’s impossible to imagine New York City without Central Park, it’s paramount to acknowledge the brutal displacement that has occurred—and continues to occur—in the city, and to attend appropriately to this history.

MLK Jr. Day is an apt occasion to remember Seneca Village.

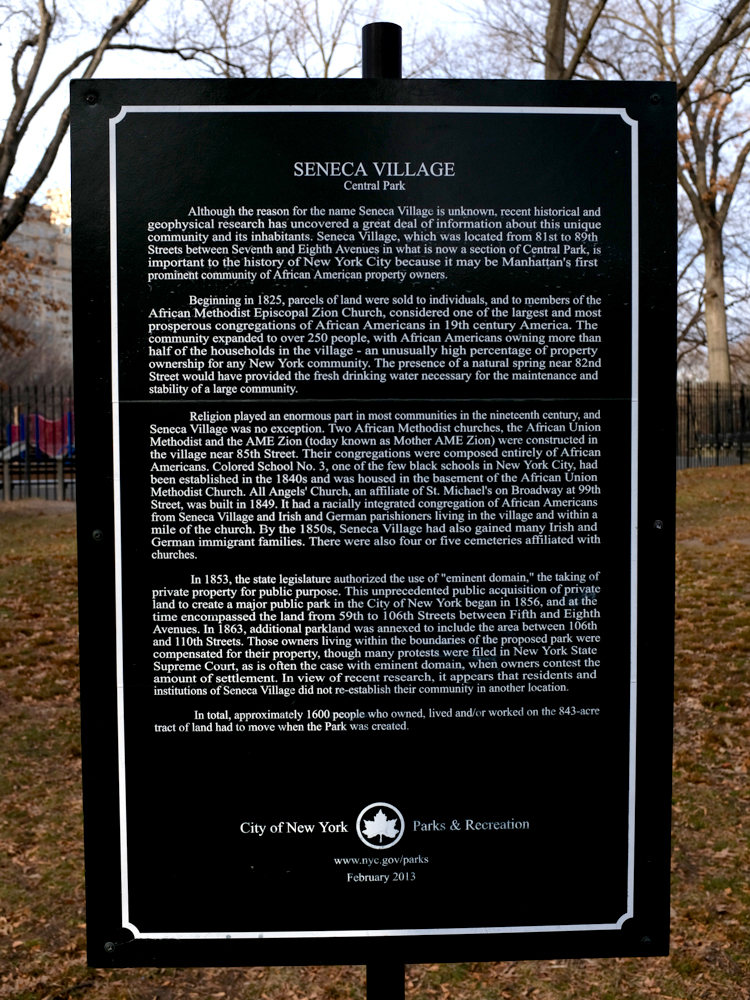

In the spring, the Conservancy will be installing a series of new signs on the Seneca Village site, to commemorate the community and raise awareness of a unique chapter in New York City history. Below is one sign already installed in the park.

This is an outstanding article. I learned a lot. Thank you WSR and Michael McDowell.

Poet Marilyn Nelson has written a wonderful”bio”

poetry book for children/ young adults

about this village ( several years ago)

The author is the former poet laureate of CT and I think now teaches in VA Jane

In the Early 2000’s, prompted by the discovery and subsequent saving of the African Butial Ground in Lower Manhattan, Cynthia Coleman of the NY Historical Museum and the Office of then Senator David Paterson, the Primary Leader of the saving and study of the African Burial Ground began a study of Seneca Villege. With the help of local archaeologists, and the NY Historical Museum did a fairly complete servey and study of the Village, including the above ground servey referred to in your article. Any digging was banned by the Parks Department. The marker shown in your article was prompted by this study and the NYC Landmarks Preservation Comission’s interest in finding out the history of this section of NYC and Central Park.

Tours with the children from local public and several Private did the tours and scoured the top level of the area—finding a number of items from Seneca Village.

I believe this study is avalible at the NY Historical Society. I was Sen. Paterson’s point person on both

The Africa Burial Ground and the Seneca Villiage studies.

I’m glad they will be improving signage. People should know the history of the land they’re enjoying the use of.