*ICYMI stands for In Case You Missed It. It indicates that the story was already posted but is still or again timely.

By Giulia Leo

On April 8, New Yorkers will don special protective glasses to watch the moon swallowing the sun in a total solar eclipse. Today we know the science behind the phenomenon, but ancient cultures struggled to understand it. Some believed a giant animal or demon was trying to eat the sun. Others saw it as an evil omen, signaling impending death of a king or possibly presaging a war. Then there is the story told by the Haudenosaunee people, a Native American confederacy whose traditional lands include part of what we now call New York state.

When Perry Ground’s image pops up on a Zoom call his face is framed by a traditional Native American feather headdress. Ground is an Indigenous storyteller, a member of the Haudenosaunee, and among his many stories of Native American life is one about the Haudenosaunee and a solar eclipse.

“The Haudenosaunee are a confederal nation of originally five, today six, different tribes,” says Ground, who belongs to the Onondaga Nation and currently lives in Rochester, New York. The Onondaga, the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Cayuga, and the Seneca were the five original Haudenosaunee tribes, also known as Iroquois (a name the confederacy considers derogatory because it means “black snakes”).

The confederacy was formed about a thousand years ago, “when a very, very important event happened: the sun disappeared,” Ground says. “There was a total eclipse, and that was one of the signals for us to join together after centuries of fighting.”

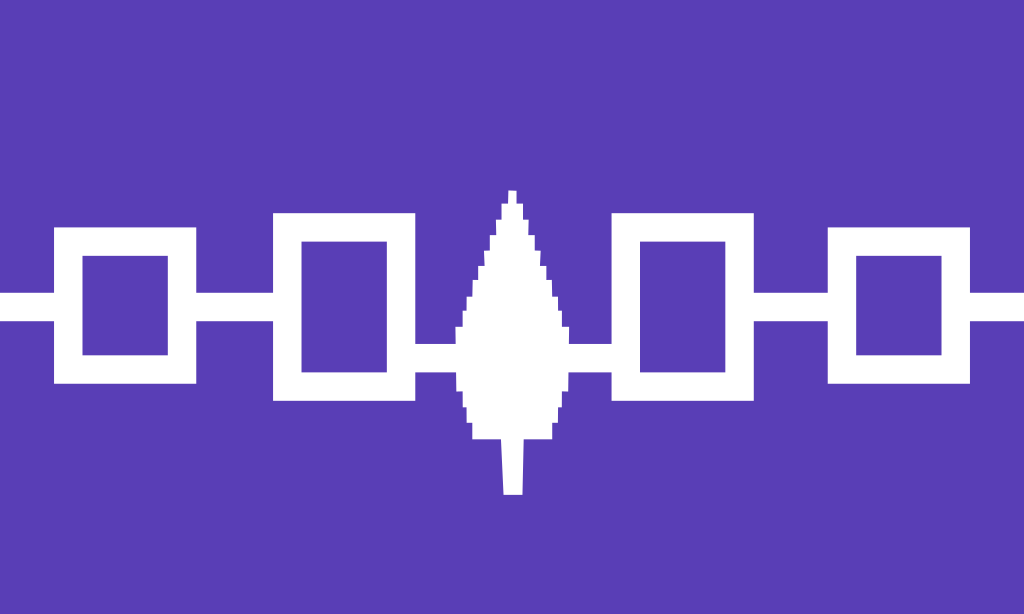

As Ground tells this story he points to a brown and purple blanket on the wall behind him – a wampum belt with four rectangles connected by a line. Each represents a tribe: Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Mohawk. The fifth tribe is represented by a tree in the center, symbolizing the Onondaga land where the five tribes finally agreed to make peace under Hiawatha, an Onondaga and the confederacy’s cofounder.

According to the legend, Hiawatha traveled through the five nations with a prophet, who was sent by the Creator and known as the Peacemaker. Their goal was to unite the tribes, which had been at war with each other for centuries. Hiawatha and the Peacemaker found their message quickly embraced by the Mohawk, Oneida, and Cayuga tribes. But the Seneca and the Onondaga resisted.

When the Peacemaker recognized that the Seneca were not ready to accept the new message of peace, he left, promising to return later to complete his mission. In the meantime, he instructed the tribe to search the sky for a sign from the Creator.

Nothing happened for a year. Then, finally, the Peacemaker came back, and upon his arrival a total solar eclipse made the morning sky turn black. At first, the Seneca were scared, but soon they recognized it as the sign from the Creator they had been waiting for; it was time to join the confederacy.

That left just the Onondaga, whose fierce and violent leader Tadodaho was still resisting peace. In the end, Tadodaho agreed to join the confederacy on the condition that his nation would become its capital. Thus was born a new union of former enemies.

When they made peace in Onondaga, the tribes buried their weapons in the ground (Native American educators say this likely is where the phrase “bury the hatchet” originated) and planted a tree to symbolize the end of the conflict and the beginning of a new era of peace. That’s why, Ground says, the Onondaga Nation is represented by a tree at the center of the wampum belt.

The Haudenosaunee originally were located in what is now upstate New York. “The Onondaga lived through that corridor that goes from Lake Ontario, north of Watertown, down through Syracuse and then down south towards Binghamton,” says Ground, while the Mohawk lived in territory northeast of there, stretching to today’s Schenectady. The other three tribes lived in and around the Finger Lakes region. Haudenosaunee people today live in reservations and off-reserve communities in southern Ontario, eastern Quebec, and upstate New York.

When the eclipse happens on April 8, many of the Haudenosaunee people in New York state will be in the path of totality. But Ground says they are not likely to perform any ceremonies or rituals to commemorate the long-ago eclipse that brought them together in peace.

This doesn’t mean the story of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy is destined to be forgotten. For centuries, grandparents have told it to their grandchildren, who in turn share it with their children, and their children’s children. That’s how Ground learned the story.

“I was the child that wanted to sit with my grandmother and my great-grandfather and listen to these stories,” he said. Now, Ground puts on storytelling shows all over New York state. In the runup to next week’s eclipse, he’s booked daily performances, often at local libraries, telling stories of Native American traditions of eclipses – from the Cherokee belief that blames the eclipse on a giant frog eating the sun, to the unification story of the Haudenosaunee.

Ground discovered his love for storytelling at Cornell University, where he met a graduate student who was also a Mohawk storyteller. “I saw the power of stories,” he says. “I saw how it can bring people closer to Native American history and culture and impart a positive message about who we are as Ogwe•oweh, [a Seneca word for] human beings.”

Subscribe to West Side Rag’s FREE email newsletter here.

Wonderful – thank you for this story of how peace was made . Oh, If it were only possible to have nations do that now.!

What a great story. Thank you!