By Bonnie Eissner

From domestic labor to sex work, practicing medicine to making clothes, women’s labor is ubiquitous, defies categorization, and is political.

That’s the premise of “Women’s Work,” an exhibition that opened this summer at the New-York Historical Society. Using 45 objects from the museum’s collection, it explores the ways women have worked in and outside of their homes in New York since the 1700s.

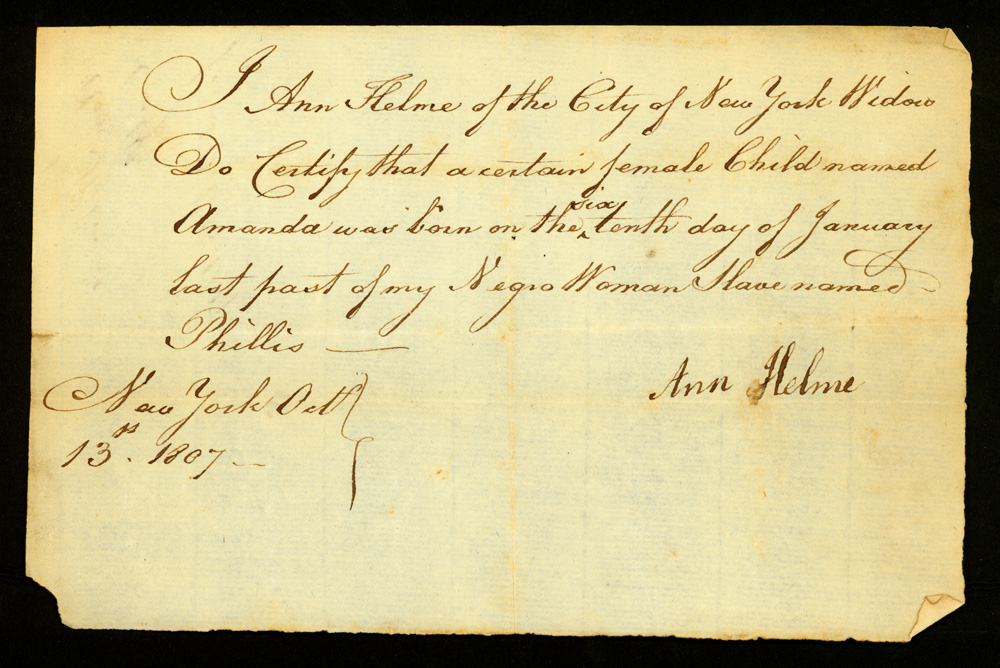

“What is ‘women’s work’?” asks a question posted on a wall at the opening of the show. And from the first group of objects — a birth certificate for a child who was born to an enslaved woman in New York in 1807 and a book of girls’ indentured labor contracts from about a decade later — the curators offer some tough and unexpected answers.

“We wanted to make it very clear that not only in many cases were women not paid for their work, but in many cases their work was not free,” said Jeanne Gutierrez, a curatorial scholar at the museum and a CUNY Graduate Center Ph.D. candidate, who co-curated the exhibition with colleagues from the museum’s Center for Women’s History.

The show avoids chronology and rigid organization. Rather, the objects are grouped by broad themes, such as domesticity, advocacy, and the arts. Translucent walls allow visitors to peer from one section to the next and follow their curiosity rather than a defined path.

Many of the objects tell multiple stories. A stunning 19th-century mahogany cradle owned by the wealthy Gallatin family has two labels: one about women’s traditional roles as caregivers and the other about the indentured Black nurses who likely cared for the family’s babies.

Teaching, like caregiving, has long been considered acceptable women’s work. A graffiti-scarred, 1911 oak desk from DeWitt Clinton High School prompts an examination of the 19th-century notion that “school-keeping” was not only a natural extension of women’s work in the nursery, but that women teachers would free men up for more lucrative jobs.

The curators explore the pink-collaring of other professions, such as the now defunct role of telephone operator. Women, who surged into the role during World War I, replaced teenage boys, who were considered too rude. In the 1930s, automation eroded demand for the job, but the wartime work of women was not in vain, as the show points out. By taking on men’s roles as ambulance drivers and nurses, women changed how people, including President Woodrow Wilson, viewed the 19th amendment.

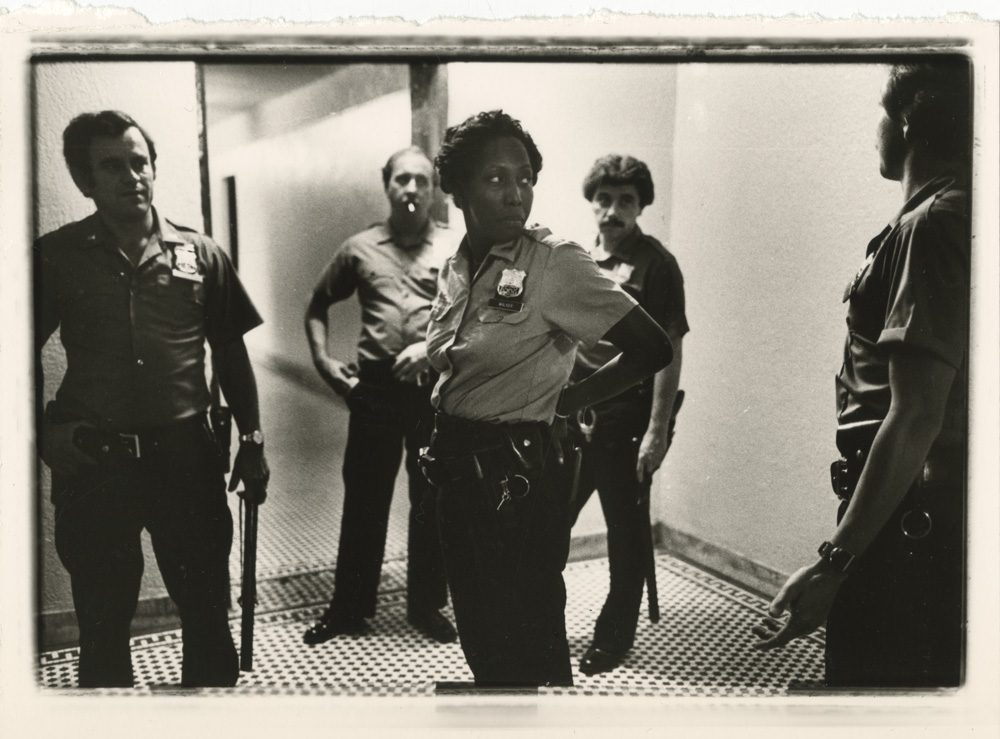

Other fields, such as medicine and law enforcement, have presented bigger barriers to women. The exhibition tells compelling stories about the women who broke into those careers. A captivating 1970s photograph (at the top of this story) by Jane Hoffer, simply called “Officer Walker,” shows a female police officer looking askance as two men behind her assume equally questioning, tough guy poses

New York became the first U.S. city to let women work in law enforcement in 1854, but only as jail matrons. Still, the matrons paved the way for women to sit for civil-service exams and receive firearms training in the 1930s. It took a 1960s court case for women to be promoted to the upper ranks of the police department. Hoffer, who photographed women on police patrol in the 1970s, observed that the women broke stereotypes. “They were physically competent; they were in authority; they lived in danger and carried a gun,” she wrote. “And they were working as equals to men.” Yet, only last year did Keechant Sewell become the first woman to serve as commissioner of the New York Police Department.

When breaking into the mainstream wasn’t possible or even desirable, women carved new paths to profit or influence. In the second half of the 1800s, as Indigenous people were forced out of their lands, Haudenosaunee women adapted their beadwork to make elaborate pincushions and other souvenirs for the tourists who flocked to Niagara Falls. A pincushion about the size of a dinner plate depicts a bird bearing two American flags. The motif oozes a patriotism that was likely unfelt by its maker.

The pincushion embodies several of the exhibition’s threads. There are ties to sewing and fashion design, which are echoed nearby with a photo of women working in a Chinatown sweatshop in the 1980s and a pair of 1970s Herbert Levine black leather pumps, which were actually designed by his wife, Beth Levine.

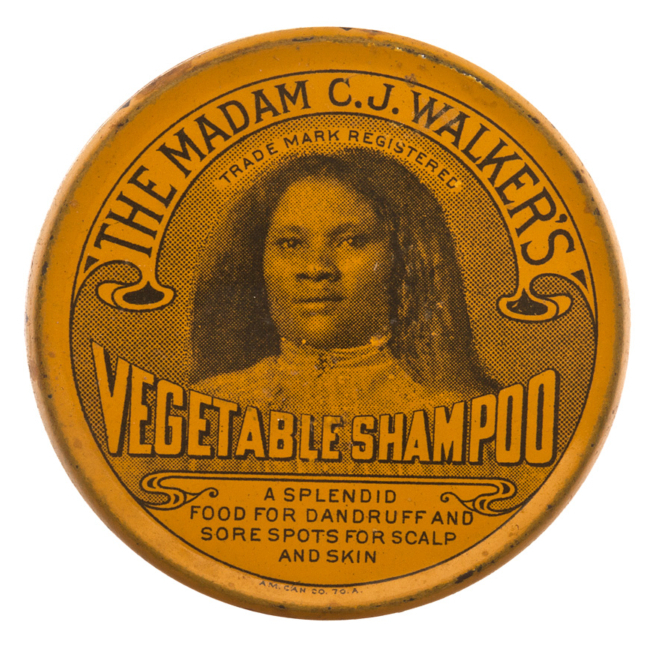

A tin of Madam C.J Walker’s Vegetable Shampoo links to the theme of entrepreneurship. Born Sarah Breedlove in 1867, Walker became a self-made millionaire with the success of her Black hair-care company.

Marginalization, another theme, resonates in a matchbook from the Sea Colony, a lesbian bar in the 1950s and ’60s that was frequently raided by the police. Close by, a photograph shows a transsexual sex worker on “the stroll,” an area of the Meatpacking District in the 1980s. Faced with discrimination, many trans people still consider sex work their only viable job.

The exhibition is full of other clever mashups. A section on Black women’s political activism pairs a photograph of Sojourner Truth with a portrait of gay rights activist Marsha P. Johnson. On the same wall hangs a National Welfare Rights Organization campaign button demanding “Welfare rights NOW!” Many single women of color joined the welfare rights movement that emerged in the 1960s to protest policies that remunerated women for caregiving work outside but not inside their homes. In a 1972 essay in the inaugural issue of “Ms. Magazine,” NWRO leader Johnnie Tillmon wrote, “If I were president, I would solve this so-called welfare crisis” by “issu[ing] a proclamation that ‘women’s’ work is real work.”

Anna Danziger Halperin, a co-curator of the show and the associate director of the Center for Women’s History, said that the curators considered putting Tillmon’s quote on the wall at the beginning of the exhibition. “I mean,” she said, “that’s actually making the point of our entire show.”

Sex work?

The consequences of this deranged linguistic re-frame of women’s systematic sexual exploitation for male pleasure are dire.

Like how in Germany if a woman needs a job, she can’t draw unemployment if she turns down being a prostitute.

The most woman-hating man I know is pro-prostitution. He calls it “sex work” because he likes how clinical it sounds, as if it’s not the most dangerous, inhumane of men buying physical access to the most vulnerable of women. He also says we can install “panic buttons” for when things go wrong. To him, a “little bit” of rape is fine, for a certain class of woman.

Tragic how academic women have abandoned their solidarity with girls and women around the globe. Being prostituted is what happens when a woman has no better options. Being prostituted is what happens when the worst type of men believe that they have a right to buy women as objects.

1. Consent cannot be coerced. Needing money to live is coercion.

2. Consent can be revoked at any time. If you’re trapped in a room with a man who has paid to rape you, how could you dare revoke consent, or deny any sexual act no matter how degrading or violent? Not to mention that you simply physically could not do so because of the strength differential between men and women.

3. Consent is enthusiastic. Look at the men who walk past you on the sidewalk. Choose the one who frightens you. Imagine you have to let him rape you in order for you to survive.

All women and girls have a right to live free of sexual violence and exploitation. The only difference between the woman reading the comment and the woman (or girl) in prostitution is her circumstance.

The female academics who have abandoned global solidarity with women as a sex class should be ashamed of themselves. But more than that, they should exit their fantasy in which all “sex workers” are well-paid happy elegant Julia Roberts, and they should start to make things right. Playing language games and renaming prostitution to “sex work” because it sounds better is not actually making women safer. Female academics, you can work to make this right. Leave behind the friendly smile while encouraging some women’s dehumanization.

the ‘sex workers’ they are featuring as doing ‘women’s work’ are actually males

A woman cannot be denied unemployment benefits for declining to engage in sex work in Germany. The policy was clarified by German job centers in 2004 following legalization in 2002.

Thank you Ellen for posting this!

Thank you., Ellen, for calling this out. There never seems to be an end to the different ways in which women can be insulted, degraded and marginalized.

I love it when I read an article that inspires me to get out and see something in the neighborhood and that’s what the West Side Rag does while also keeping us informed. It’s a treasure and now thank you to Bonnie Eissner for this wonderful piece of writing that will get me over to the New York Historical Society for the Women’s Work exhibit for a great New York experience.!