By Peggy Taylor

“The messenger was given a very slow mule to ride.” Today, Black Texans from Galveston joke when asked to explain why their ancestors were the last slaves to learn that they were free. Why they didn’t know that the Emancipation Proclamation, signed by Abraham Lincoln, effective January 1, 1863, guaranteed that…

“…all persons held as slaves within any state or designated part of a state… shall be thenceforward and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and Naval Authority thereof will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them in any efforts they make for their actual freedom.”

According to the Juneteenth Legacy Project, “Few Union troops were available in Texas to enforce the law. Enforcement of the declaration generally relied on the advance of Union troops, which was delayed due to continued rebel resistance.” Slaves had no access to newspapers or the telegraph, because they couldn’t read. Slaveholders were in no hurry to see the status quo upended and so withheld the news.

On June 19, 1865, two months after Lincoln was assassinated, Brigadier General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston by ship. He came ashore with 1,800 Union troops and read Order #3:

The people are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, become that between employer and hired labor. The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

A little-known fact about General Granger’s contingent is that his troops included Black soldiers and sailors from the United States Colored Troops (USCT) who had been a part of the Union forces since May 22, 1863. (The all-Black 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry was celebrated in the 1989 film, “Glory.”)

On his arrival, Granger fortuitously found an additional 5,000-10,000 USCT soldiers from the 28th Indiana, 29th Illinois, and 26th and 31st New York Regiments, who had dropped anchor in Galveston Bay on June 18th after rough seas forced their ship to divert to Galveston for supplies.

Carrying out Granger’s orders, the troops fanned out through the state’s cities and countryside and spread the news. They read the order at various locations throughout the cities; they posted the order on buildings and churches; they published the order in newspapers and advised slaveholders by word of mouth that their slaves had to be freed.

In an interview for the WPA (Works Progress Administration) Slave Narratives in 1937, former Galveston slave Pierce Harper remembered: “When peace come June 19th, 1865, they read the Emancipation law to the colored people, they spent the night singing and shouting they wasn’t slaves.’’

Photo Credit: Juneteenth Legacy Project.

Here we see USCT soldiers with General Granger on a 5,000 square-foot public art mural, “Absolute Equality” by Artist Reginald Adams, unveiled in Galveston in June 2021 when Juneteenth became a federal holiday.

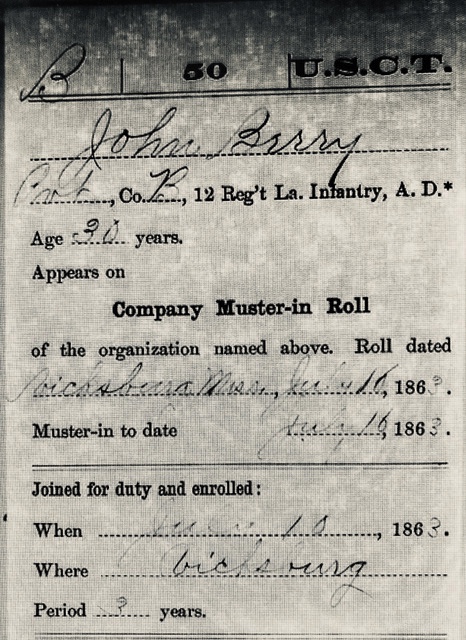

In 2017, at age 77, I discovered that my great-great-great grandmother’s second husband, John Berry, had joined the Union Army on July 10, 1863, and served for three years. This I learned from a college classmate, Civil War buff, and amateur genealogist, David Dreyer. To him I am forever grateful. His revelations sent me to the National Archives in Washington to learn as much about Berry as I could.

Scrolling excitedly through Berry’s paper trail, I found his Muster-in Roll Record noting that he joined the USCT in Vicksburg, MS, on July 10, 1863, and served for three years.

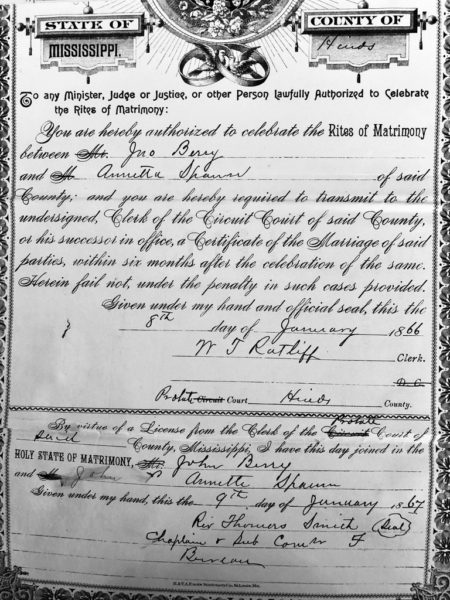

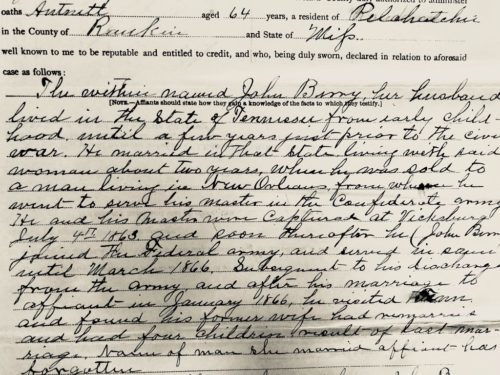

Then I found evidence of his marriage to my great-great-great grandmother, Antnett Spann (11/10/1827- 2/1/1917). (Different spellings were often given for her first name.)

Then Antnett’s fascinating account of Berry’s early life– his first marriage, his sale to a slaveholder in New Orleans, their capture by Union soldiers in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Berry’s joining the USCT in Vicksburg in July 1863.

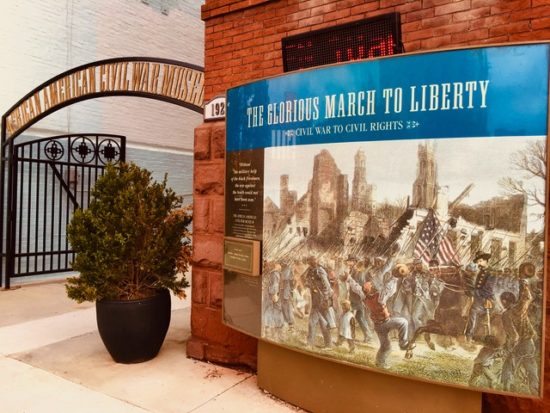

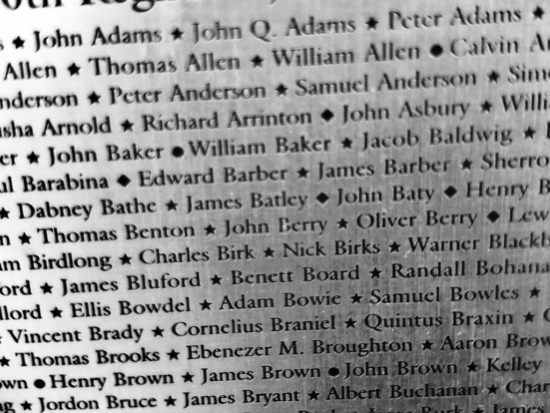

After visiting the National Archives, I toured the African-American Civil War Museum dedicated to the USCT. There I found Berry’s name among the 209,145 inscribed on the Museum’s Memorial Wall. (Dedicated on July 18th, 1998.)

Is this what John Berry looked like?

I’ll never know. Most photos of military men at that time were of the top brass, not of the rank and file. And Black soldiers, even when photographed, were often listed as “Unidentified African American Soldier.” So, I’ll just imagine that this was him proudly having traded his dusty, field-hand overalls for a United States Infantry uniform. I’ll also imagine that he was with Granger’s troops who brought Galveston the good news.

Ms. Taylor’s tenacious research into her family member John Berry is most interesting and is an important reminder to all of us. Having spent my K-12 years a short drive from Galveston, the fact that our Texas City High School School District was not fully integrated until 1969, and that Black high school students were bused to Galveston until 1953 when a Black high school was built in Texas City, sadly illustrates our country’s past, present, and growing racism.

This should have been a holiday for a long time.

Fascinating story!

Wonderful to learn of a fellow UWSer’s family history… and ancestor’s service!

What a wonderful story. I am horrified, and astonished at my ignorance, that I didn’t know word of the emancipation didn’t reach Texas for 2 1/2 years after the proclamation.

You’re not the only one. I bet the majority of Americans didn’t know. I certainly didn’t.

Thank you so much for sharing this story.

You’re so welcome. I’m glad you found it worthwhile.

Thnx, Peggy, for your scholarship and insatiable curiosity.

You’re welcome. It was profound revelation to me. Even the friend who put me on Berry’s trail was astounded at the information I found at the National Archives.

You did a great work researching the story of your family. Congratulations and happy Juneteenth!

Thank you! It was indeed a meaningful Juneteenth.