An earlier version of this article was posted on the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group website. The sources and photo credits are listed there.

By Pam Tice

In this month of promoting women’s history, it’s a good time to remember an Upper West Side woman who entered the public sphere in New York City more than 100 years ago. Working for the Boston founder of Christian Science, Augusta Emma Simmons Stetson came to New York City and built the First Church of Christ, Scientist at Central Park West and 96th Street. Soon it will become the Children’s Museum of Manhattan, plans you can view here.

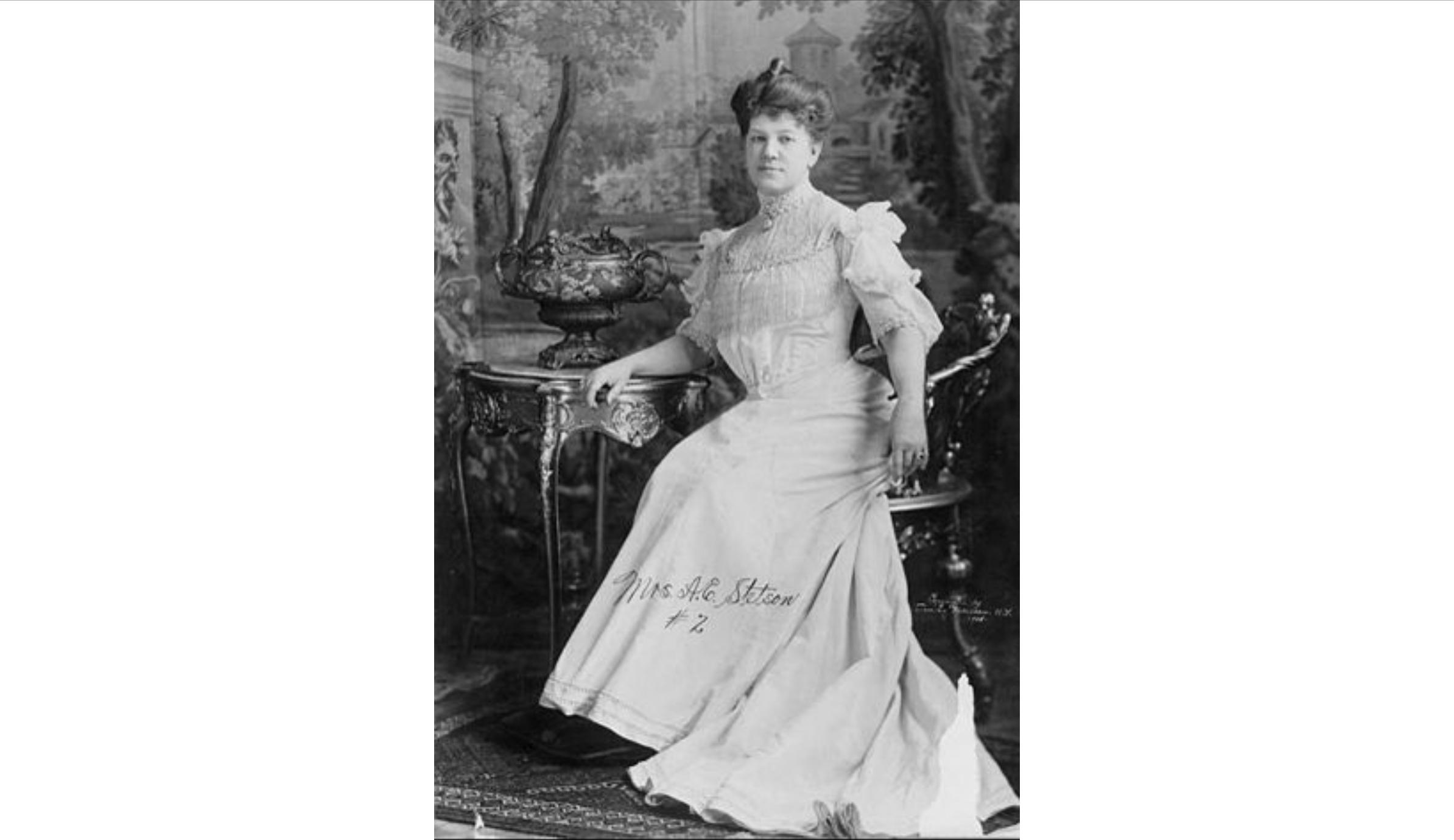

Augusta Simmons was born into a modest family in Maine in 1842. She married Captain Frederick J. Stetson, a shipbuilder associated with a company in London. For a number of years, the couple lived overseas in London, Bombay and Burma. Captain Frederick’s ill health brought them back to Boston where Mrs. Stetson enrolled in a school of oratory, hoping to become an elocutionist at a time when the public lecture circuit was popular. She is described in many biographies as tall, elegant in appearance, with a charismatic personality and a resonant voice. At a time when women were not afforded an opportunity to be in the public sector, she appeared to be breaking barriers.

In 1884, she met and was then recruited by Mary Baker Eddy to be trained at the three-week Massachusetts Metaphysical College, founded by Mrs. Eddy to teach the metaphysical healing she called Christian Science. At a time when the medical profession did not have a solution to many health problems, this method of healing appealed to many people who were suffering.

In 1886, Mrs. Stetson was dispatched to New York City to establish the new religion here. Others were organizing here too, especially Laura Lathrop who became Stetson’s rival. But Augusta Stetson (named “Fighting Gus” by some) was successful, developing a devoted following, and organized the First Church of Christ, Scientist, in 1887. Lathrop would organize the Second Church, building her church further south on Central Park West at 68th Street.

Stetson became controversial as her power grew, challenging Mrs. Eddy’s leadership, and declaring her church to be the only one in New York City. She developed a domineering attitude and called people names who disagreed with her. Her personality and many of her actions make it hard to celebrate her, but we do recognize her accomplishment of building one of our finest landmarked churches.

Scholars label Mrs. Eddy an ambivalent feminist, founding a radical church but placing its management in the hands of an all-male Board. As more complaints about a despotic Mrs. Stetson grew, Mrs. Eddy used her Board to try to deal with her — changing the rules to control her, eventually publicly reprimanding her, and finally excommunicating her.

Augusta Stetson began to raise money for her church building, laying its cornerstone in 1899. Initially, the church was to cost $500,000, but soon grew to over a million dollars, as expensive design choices were made, including the use of Concord granite and the installation of two elevators. In 1903, when the church was dedicated, Stetson flaunted her accomplishment of raising such a hefty sum, unlike her rival Lothrop who had a mortgage on her church.

The First Church’s wealthy congregation sought a building that would signify respectability, choosing the prestigious architects Carrere & Hastings, and using the finest materials throughout the internal structure. Famed artist John LaFarge made the stained-glass window over the main entrance. The Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group has uploaded a copy of a real estate brochure with photographs of the Beaux Arts interior of this beautiful building before it was gutted.

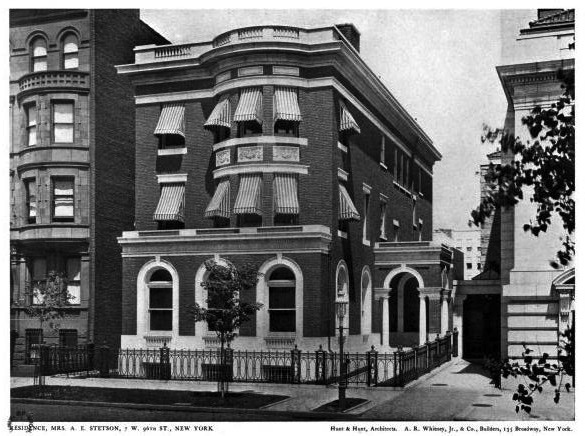

The year after the Church was dedicated, Stetson’s devoted congregation built her a mansion just behind the church on West 96th Street. Designed by Hunt & Hunt, the architectural firm of Richard Morris Hunt’s sons, the mansion had a one-story portico with marble columns at its side entrance.

In 1909, with the First Church welcoming overflowing crowds, Mrs. Stetson began making plans to develop a second church building at Riverside Drive at 86th Street. However, this violated guidelines set by the Board of the Church in Boston, and the plan was dropped. An investigation of Mrs. Stetson also began that year, looking at her unorthodox views of Church teachings, her practices, and the fact that she gave false testimony in a court case. The Boston Board revoked her license as a Christian Science teacher and practitioner, excommunicating her from the Church. When Mrs. Eddy died in 1910, many expected Stetson to return to head the church, but she did not. She kept her mansion, and kept her title as principal of the New York City Christian Science Institute.

Stetson continued to publish pamphlets on her views of Christian Science, often attacking the “Mother Church” as “exhibiting spiritual decline.” Many New Yorkers continued to follow her, with as many as 800 attending her lectures. In 1918, she formed a Choral Society as part of the Institute, and took on a cause: changing the third stanza of the Star-Spangled Banner because it was too militaristic.

In 1921, Mrs. Stetson was in the news again regarding a suit against the First Church to stop them from erecting a brick wall at the rear of the church that would cut off her light and air.

Stetson purchased a radio station in 1925, broadcasting five times a week. She promoted ugly propaganda that was anti-Catholic and antisemitic, advocating white supremacy and traditional American virtues.

Although she had once claimed immortality, Augusta Stetson died in 1928. Her residence was demolished soon after, and an apartment building replaced it in 1930.

As for the First Church, its congregation shrank over time, not unlike many other neighborhood churches. The building was declared a New York City landmark in 1974. In 2005, the First and Second Churches finally combined. The Crenshaw Center East, a nondenominational church from Los Angeles, purchased the First Church building in 2004 and held services there for a decade. In 2014, a developer purchased it with the intention of converting it into condominiums, but the project failed to get approval. Now the Children’s Museum of Manhattan will convert it and join the neighborhood’s other important institutions.

At the time the church building at 361 CPW was landmarked, it was thought that John LaFarge had designed the central stained glass window. Most recent research, however, suggests that the unsigned window was designed by Herman Schladermundt, who did work for Carrere & Hastings in those years. Some of his windows were made by the Decorative Glass Company, who seem to have made the windows in the First Church. The late Mary Clerkin Higgins assembled material about Schladermundt. I don’t know whether she was able to publish it before she died in December of 2020.

Herman T. Schladermundt designed stained glass windows that remain in the Library of Congress, the Missouri State Capitol, and numerous other buildings. He also painted murals.

from ronne: Great seeing you today. Here’s the article I mentioned at lunch today about the church on 96th and CPW. Enjoy the weekend.