For twenty years the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group (BNHG) has promoted research and education on the history of the Bloomingdale neighborhood of New York City’s Upper West Side. Bloomingdale is the name of the neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan from W. 96th to W. 110th Street between Central Park and Riverside Drive. This area has been referred to as “Bloomingdale” for over 300 years.

This post, and the two that will follow on successive weekends on the same topic, are written by Pam Tice, BNHG.

In the early days of the nineteenth century as the population of New York City expanded, how to care for elderly citizens, particularly the poor, became a problem. Until then, old people were cared for by their families, or taken into the home of a friend. Poor people who ended up in the City’s Poor House were not differentiated from the mentally ill or dissolute people who were unable to care for themselves.

One of the West Side’s historic organizations, the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females, was formed in 1814 to deal with the problem of poor elderly women. The history of their Home at 891 Amsterdam Avenue (103-104) has been covered in an earlier post but will be described here again, with new information recovered from a trove of their Annual reports discovered at the New York Public Library.

Five other homes were in close proximity, starting in the late 19th century and into the early days of the 20th century, some lasting until the 1970s when everything changed with new Federal programs. This three-part series covers the history of caring for the aged in our neighborhood at these institutions and two others from more modern times, covered in Part 3.

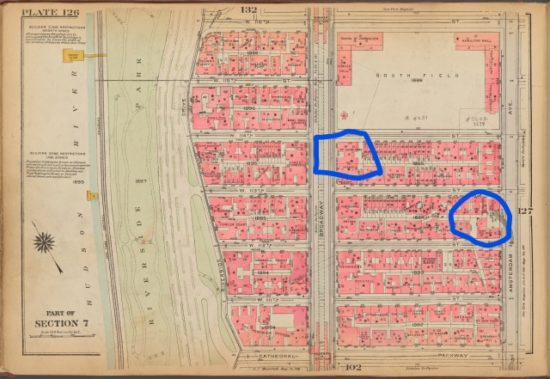

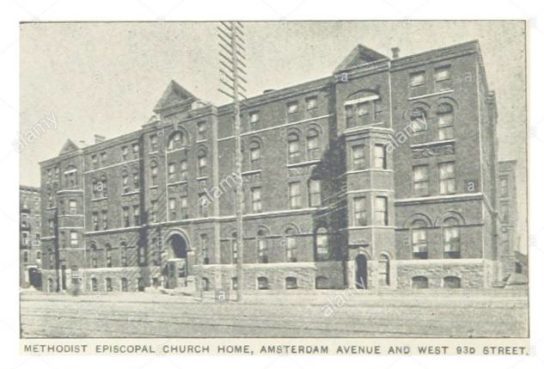

The Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged at 673 Amsterdam Avenue, between West 92nd and West 93rd Street

The Home for Aged Hebrews, originally located at 121 West 105th Street

The Old Age Home operated by the Little Sisters of the Poor, at 135 West 106th Street

Across 110th Street in the Morningside Heights neighborhood,

The Home for Old Men and Aged Couples at 1060 Amsterdam Avenue at 112th Street

The St. Luke’s Home for Aged Women at 2914 Broadway at 114th Street

Introduction

While the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females got an early start in 1814, as the nineteenth century progressed other organizations formed to care for the elderly, at first for old women, and later for men. Older women were expected to be in need of support, but it took a while longer for men to be viewed in the same way. While numerous homes were operated by religious organizations, there were others established by mutual aid societies of workers’ organizations, or by certain immigrant groups. Today, for instance, we still have the buildings of Sailors Snug Harbor where “aged, decrepit and worn out” sailors were cared for, starting in the 1830s.

Over time, the religious organizations, particularly Protestants, defined those who deserved their support, extending it to those who were poor because of illness or loss of fortune in contrast to those who could not take care of themselves or their families, perhaps through alcoholism. Even as they became adept at managing an asylum, groups turned away those who were mentally ill, leaving them to go to public institutions. In general, they wanted fairly healthy individuals, although they had infirmaries for those who became ill as they neared death.

Four of the six home discussed here came about as a result of the efforts of women. The two north of 110th Street, in the Morningside Heights neighborhood, were connected to the Episcopal Church, and founded by one of its pastors, Reverend Isaac Tuttle, but had committees of women who were integral to the operation. Women who engaged in charity work in the nineteenth century became adept working outside the home, extending their social influence, and learning organizational and financial management. These skills carried over to the abolitionist movement, the temperance movement, and eventually the suffrage movement.

The rules governing the position of Matron for both the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females and the Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged are remarkably similar, as if the two institutions were in close contact. The Matrons were charged with being respectful and kind to everyone, keeping the home in neat order, and enforcing the rules. The lights were to be extinguished by 10 pm, with others left burning throughout the night only as needed. No “spiritous” liquors were allowed unless a physician had ordered them, and then the Matron had to keep the supply and administer it. She was responsible for the preparation of meals, for the quality of the food, the timing of the meals, and that the prayer of grace was said at each meal.

The women managers of the Home performed many duties that would later be handled by staff: ordering supplies, visiting each resident regularly in committees of two, visiting those they supported outside the home, and delivering clothing, food, cash and sometimes fuel.

Three of the homes in Bloomingdale were designed by the firm D. & J. Jardine. David and John Jardine had immigrated from Scotland and formed one of the prominent firms in the city. They designed the asylums built by the Little Sisters of the Poor, the Methodists, and the B’Nai Jeshurun Ladies Benevolent Society. Landmark West Jardine buildings are still standing in the West 80s. Research underway by one of the members of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group has identified 910 Amsterdam Avenue, 200 to 208 West 105th Street, and 202 West 108th Street as D. & J. Jardine buildings, all still standing.

As time went on, and the population of elderly citizens increased, facilities changed. When Social Security began in the 1930s, there was a general increase in care homes in the U.S. and the “poor house” came to an end since those committed there could not receive Social Security payments. During the Depression, many people opened up their own homes to old people since they brought some income, although we have no particular knowledge of this activity on the Upper West Side. Finally, after World War II and beyond, when Medicare and Medicaid began, nursing homes became a business, and had significant impact on our neighborhood.

The Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged

Just like the women of the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females, and those of the Home for Aged Hebrews, the women of the Methodist Churches in New York City followed a similar path. They wanted to do something about caring for elderly women who faced the almshouse. In 1850, a group formed the Ladies Union Aid Society and, very quickly, a home was rented at 16 Horatio Street for 30 women. By 1857 space was tight, and they had raised enough funds to combine a two-lot gift of land with one lot purchased on West 42nd Street near Eighth Avenue. Here they built a 4-story building that housed 75 people, men included.

The residents, referred to as “the Family,” had to belong to one of the many Methodist churches in Manhattan and apply through their own church. Every church had a committee to consider applicants. They did not accept anyone who was “insane or weak minded.”

The Methodists had the usual “subscriptions” (annual donors) and those who left bequests to their Home. They accepted donations of food, clothing and furnishings, all scrupulously noted in their annual reports. They also offered two Benefits each year, celebratory events, such as an “Autumn Harvest Home Festival” that attracted church members from around the city, with special teas, and items for sale. The women in the Home always made some of the knitted and crocheted items, giving them useful work, and also helping the Home.

In 1884 they bought eight lots on Amsterdam Avenue, on the block between West 92 and 93 Streets, and by October 1886 the residents were moving into their new home. One of the physicians said, “Its very location is suggestive of health, being on high and rocky ground, and in one of the non-malarious portions of the island. The Outlook is grand with a commanding view of the Hudson River and the Palisades.”

Just inside the front door of the brick home was a chapel that could seat 400, and on the first floor there was a dining room, the Board’s committee rooms, parlors, the physician’s office, and offices for the matron and the housekeeper, along with ten bedrooms. The basement held the kitchen, laundry and drying rooms, the engine and boiler room, various closets and pantries, and a smoking room for the men.

Up on the second floor, the group’s Young Ladies Reading Association had a reading room with volunteers ready to read to those who could no longer read for themselves. The young ladies were also responsible for the Christmas celebration at the Home where each member of the Family was sure to get a gift. On the fourth floor was an Infirmary, and a small dining room for those who could not descend the stairs. All together there were 120 sleeping rooms, all with sunshine and fresh air as they faced outward on the streets or over the interior courtyard.

Anyone who could do so was expected to assist in the work of the Home. Several physicians donated their services, and various Methodist ministers came to preach on Sunday afternoons. There were prayers every morning and evening. Board members served on various committees, performing tasks that today would be handled by hired staff. The Visiting Committee, in two-person teams, was charged with coming into the Home three times a week, one of them at a mealtime, and getting to know the residents and hearing their stories.

Residents were not required to pay a fee to enter the Home, but they did have to turn over all of their property to the Home. Visitors were allowed only on Tuesdays and Thursdays. The Home had cemetery plots at Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn and Maple Grove Cemetery in Queens.

News reporting on homes for the aged tended to focus on the members of the Board, gifts and bequests they received, and their building and expansion projects. Any comments about the residents were usually focused on how happy they are, and the home’s lovely atmosphere and comforts. In a 1906 news report, the Home’s annual “Christmas Market,” just after Thanksgiving, was held at the Home. The reporter focused on a blind woman, Jane Bennett, who, despite her lack of sight was able to make two pretty napkin rings with beads strung on wire and a pincushion shaped like a wheelbarrow. Another woman, age 97, who had been at the Home and the earlier one for 48 years, enjoyed the event, dressed in her “pink shawl and white tulle cap with ruchings and rosettes.” An old man, a “seadog,” in a sealskin visored cap and Uncle Sam chin whiskers” was helping collect payments for the items, and chatted about his days as “a mate or second-mate on ships from ’56 to ’60.”

The Methodist Home has two written histories, one from its founding to 1892 and the other from 1850 to 1950. The second report gave a few details about the effort to relocate the Home in Riverdale. In the 1920s, the Methodists conducted a fundraising campaign, and, at the end in 1927, concluded that their Amsterdam Avenue property was worth more to them if they sold it and built a new home.

The members of the “Family” were not happy with the plan to relocate much further uptown. One resident lamented that she would no longer be able to “go the Five and Ten, or walk down the Avenues to look in the shop windows.” But the plans went forward, and the new home was occupied in September, 1929. The history book provides the details of moving the elderly residents, getting them to part with years of accumulations and to leave their rooms with the walls covered with “pasted illustrations.” Each resident had a strong-minded volunteer assigned so that excess clothing could be tossed out, although one elderly woman insisted on bringing her heavy tailor’s iron, although she did agree to leave behind her corset covers.

The plan to sell the Amsterdam Avenue property was thwarted by the Depression, so the property was instead leased for twenty years. One source says it was vacant until 1940 when it was taken down and two six-story apartment buildings were built.

Sources used for this article and the two that follow will be posted following Part 3.

Read all of our Weekend History columns here.

“As time went on, and the population of elderly citizens increased, facilities changed.” SOUNDS LIKE CURRENT EVENTS HERE.

“the Methodists conducted a fundraising campaign, and, at the end in 1927, concluded that their Amsterdam Avenue property was worth more to them if they sold it and built a new home.”

Sounds a lot like the Williams saga with the Salvation Army.

Yes, I forgot about that: West End Avenue & W. 95th Str. I believe.

I really appreciate all of the History columns and the effort that Pam Tice puts into researching the topics. The history of eldercare is indeed a subject to study, as a lot of the stigma attached to eldercare comes from its early association with poverty and sometimes mental illness. What impressed me this time is that there has always been on the UWS a relationship between women who wanted to make a difference and the resulting benefits for those who needed their support. If sometimes this intention went awry, we can still see that same issue today, the continuing conflict between idealistic intentions and corruption or exploitation.

Pam Tice’s history of our community’s relationships with older adults who needed help in later years reminds us of our responsibilities and opportunities re elders living in nursing homes today. Congratulations to Pam Tice on her fine research. We look forward to her next articles on this important subject that affects and concerns people of all ages.

This is what 1060 Amsterdam Ave. looked like when it was built

https://www.instagram.com/p/B_m2gxelLqK/

It was the last home (in the 1910 US census) of my widowed great great granduncle, John Fryer, who arrived in NYC from London in 1858 and made a career as a theatrical manager.

These histories are so interesting. Thank you for posting them here.