Editor’s note: Starting today, we plan to publish a story or video each weekend showcasing the history of the Upper West Side. This week, we are very excited to present an excerpt from a book being written by Jen Rubin, whose father and grandfather owned Radio Clinic, an electronics store on 98th street and Broadway. The tale of what happened to the store in the 1977 blackout is riveting. Enjoy the story, and see the bottom of the story if you’d like to contact Jen.

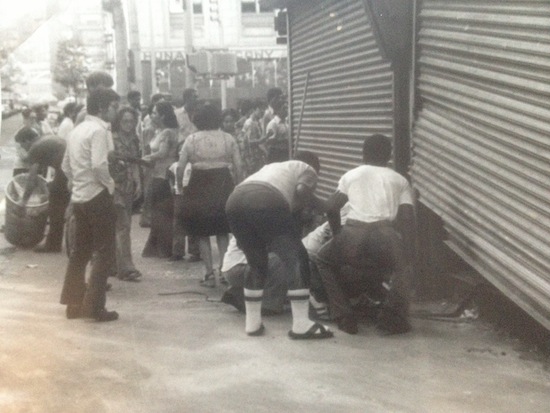

Photo outside Radio Clinic during the blackout by Alan Rubin, the author’s father.

By Jen Rubin

In the summer of ’76 I was the kid every kid wanted to be. I spent the summer working at Radio Clinic, the business my grandfather opened forty years earlier. I would stand in the glass vestibule of the store on 98th street and Broadway demonstrating to the world the very latest in modern technology, the Atari arcade video game. I mainly played Stunt Cycle, a game modeled after Evil Knievel’s infamous King’s island jump where he cleared 14 Greyhound buses. This game allowed you to turn the throttle on your arcade handlebar controller and try to equal his stunt on the screen Arcade video games had just arrived, and dad wanted me to draw the attention of the thousands of people that passed by the store each day. Using the plastic steering wheel on the arcade console as I stood in the front vestibule, I carried on a family tradition of gimmicks that started in 1934 when my grandfather put on a white doctor’s smock and sat in the storefront window fixing sick radios.

My Grandpa Leon opened Radio Clinic at a time when the streets of New York were packed tight with what we now call “start-ups.” Leon fled the Cossacks and Bolsheviks in Russia in 1920 after his father was shot and killed in the Pale. He settled in New York City when he was twelve. He learned to repair radios and turned that skill into a business when he opened Radio Clinic on 98th and Broadway in 1934. In the 1930s it was easy to get a lease and start a business. If you had an idea or a skill, money for the first month’s rent and courage to strike out on your own, Broadway was yours. It was a good way for an immigrant to plant a foot on the economic ladder and start climbing. Radio Clinic provided a solid middle class life for my grandfather.

My love of small businesses took root during the Saturdays and summers I spent at Radio Clinic. Among my other jobs, I shot the price gun’s neon stickers onto film and packs of batteries and I dusted televisions while my favorite shows were on. I did have a few special jobs such as head gift wrapper during the holiday season. But my favorite was tester of new video games.

The best reason to work at Radio Clinic was to eat all the tasty food on Broadway. My day started with a cruller from the Italian bakery, Chinese dumplings for a late morning snack, a deli sandwich for lunch and an Italian ice for the trip home. Eating was all part of the job, since I also had to run over to 100th Street to pick up fried egg sandwiches and coffee for the salesmen. To me, the business owners seemed to be the real bosses of New York. I would get an extra dumpling at the Chinese restaurant and a pickle wrapped into my bologna sandwich because I was Alan Rubin’s daughter. My grandfather started his business around the same time as Zabar’s opened and even though Zabar’s grew to have over 40,000 customers a week, I got my sandwich at half price because I was Leon Rubin’s granddaughter.

With over 500 stores between 80th and 100th street on Broadway, my grandfather was not the only immigrant pursuing the American dream in the 1930’s. Each block was filled with small shops fixing appliances, mending clothes and shoes, selling hats, flowers, fish, or stationery. The Upper West Side was then a comfortable middle class neighborhood and residents shopped in the neighborhood. My dad worked at Radio Clinic as a kid, studied electrical engineering in college, had a brief career as a metallurgical engineer at International Nickel, and then joined his father and brother-in-law in the business by the time he was thirty. In 1977, a few years after my grandfather died, my dad bought out his brother-in-law and became the sole owner of Radio Clinic.

1977 also happened to be the year of New York’s cataclysmic blackout and lootings. The lights went out at 8:37 p.m. on July 13 while the city was in the grip of a prolonged heat wave, and stayed out for twenty-five hours. Up until then, New York City’s 8 million residents were doing what they could to keep cool. Some were coming home from beaches or swimming pools. Some cooled off in the fire hydrants or escaped to air-conditioned restaurants and movie theaters. Others tried to ignore the heat by playing basketball in the park or attending a street party. Those without extra money to chase air conditioning or the stamina to ignore the heat fled their sweltering apartments and joined their neighbors on the stoop in search of even a hint of a breeze. Others drank cold beers on street corners. Anyone with a window air conditioner turned it on high and went about their nighttime business. If the air conditioner was purchased on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, odds are good it was from Radio Clinic.

When night fell, the looting began. Radio Clinic was one of the first stores to get hit. New York Police Sergeant Freud, of the 24th precinct, later described Radio Clinic as the first store he saw being looted. His was one of eight squad cars patrolling a 125-block area in the Upper West Side. At 9:45p.m. he reported that 60 to 70 men were pulling the metal gates off Radio Clinic. He stood on top of his police car with a loud speaker, attempting to address the men crashing in the doors. “I’m asking you to disperse. Go to your homes. This is your community,” he called, as recounted in a later Ford Foundation report The Sergeant’s appeal was answered with a barrage of bottles and a trash can. When he attempted to radio headquarters for back-up he wasn’t able to get through and he quickly left. By the time it ended, New York City would suffer $300 million in damage with 1,037 fires, 1,616 stores looted and 3,776 people arrested.

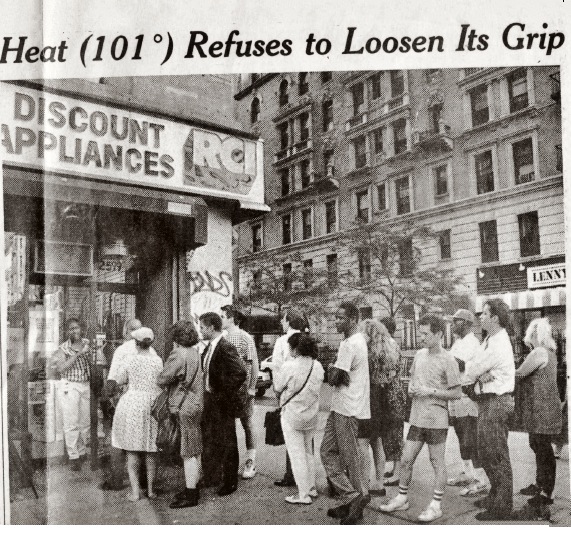

People wait to get into Radio Clinic during a heat wave, as covered in the New York Times.

My dad was sitting in a meeting on the Upper East Side when the power went out. His first thought was of Radio Clinic’s basement freight elevator so he immediately drove his car through Central Park to the Upper West Side. Of all the things to worry about during a blackout the freight elevator seems like an odd choice. But it is a simple matter of cause and effect. When the power goes off the generators stop functioning. When the generator stops functioning the water in the basement will start to rise. When the water in the basement starts to rise the elevator motor will short out. When the basement freight elevator doesn’t work it becomes a herculean task to move air conditioners and other major appliances from the warehouse basement to the customer.

Air conditioner sales during an unrelenting heat wave were not a trivial matter for my dad. During a hot summer, air conditioner sales could make up as much as a third or more of Radio Clinic’s annual sales. My dad lived in dread of a temperate summer. As a kid I could not in good conscience complain about a hot sticky day since it kept braces on my teeth. Every sweltering day brought new customers out of the woodwork. Each summer people hope it won’t be so hot that they need to spend hundreds of dollars on an air conditioner and increase their energy bill. But after a couple of days of a heat wave, most people hit their breaking point. When people come into a store looking for an air conditioner they are desperate and they want one immediately. Radio Clinic, like many small businesses, lives on a profit margin so small that a hiccup in daily operations could be ruinous. A broken elevator would lead to lost air conditioner sales, causing my dad to default on a payment to a creditor, which in turn could impact future loans from creditors, subsequent inventory and sales.

Saving the elevator turned out to be the least of his worries. After he parked his car in front of Citibank on the corner of Broadway and 96th he walked towards 98th street. He passed the police officers directing traffic at the 96th street intersection. When he reached the grassy median on 98th street he noticed a large crowd in front of the store. Looters had pulled the steel security gate up to waist level, crawled under, broken the door and were entering the store. He couldn’t tell if the crowd was passing out merchandise in an assembly line or if each individual took what he or she wanted – but either way the merchandise was leaving the store at a steady rate. My dad recognized many of the early looters as guys who lived in the SRO on 305 West 98th street between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive and often leaned against RCI’s side gate while drinking. He watched in increasing agitation until he couldn’t take another second. He walked over to a small group of looters and yelled for them to “get out of here.” When looters shouted back “you get out of here,” he realized he was greatly outnumbered and backed away.

When my dad first got to Radio Clinic he didn’t know that a confrontation had already been waged and lost by a police officer. With the power out less than 30 minutes, he thought the police could contain the situation. Radio Clinic’s large glass display windows were not broken and he hoped the damage could be minimized. It looked to him like his store was the only store on the block being looted and he went in search of law enforcement. He walked two blocks to the intersection where he knew he would find many officers directing traffic and told them about the situation. Several police officers went to Radio Clinic and were able to disperse the looters. But the police didn’t stay to watch and when they returned to the 96th street intersection, the looters returned. My father retrieved officers several more times. Finally heeding Einstein’s belief that insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results, he gave up on the police and watched the looters with mounting frustration.

I was eleven years old at the time of the blackout. My neighborhood friends and I had spent the day avoiding the heat by producing a neighborhood newspaper called the East Mayer Express. One front page story ranked the top five men and women in the country. We each wanted our parents to be on that list and I remember making a strong case for my dad to be included. He did make the top five because all the neighborhood kids liked him, and more importantly no one was afraid of him. My dad didn’t yell, he didn’t hit and if he was home he was often willing to take a station wagon full of kids to get Carvel ice-cream.

It was unreal to sit in the living room with my mom and brother watching the looting on television and knowing my dad was in the thick of a real news story. We were a fairly boring family and from the comfort of my suburban home it was strange to know my dad was in the city dealing with a situation as volatile as what we saw on the television. I was a generally anxious kid. To calm myself I would make up stories or rearrange facts. As a kid I kept a hand sized rock between my mattress and the box spring because you never know if you might be attacked while sleeping. I convinced myself that my plan to grab the rock, smash it against the picture above my bed to break the glass and in a moment of confusion take a glass shard and stab my attacker, would be sufficient to save me.

That day I was certain the tenants above Radio Clinic had boiled hot water and poured it out of their windows to scare away the looters. I was comforted to know there were people looking out for my dad and for Radio Clinic. I was surprised to learn years later that I had made up this image and the story wasn’t true.

The looting of Radio Clinic was a big moment for my family. At eleven I missed many of the subtleties of what was happening, but I did notice it was the first time I saw my dad cry and that the tension level ratcheted up considerably in my house. But I had an eleven year old’s unshakable belief in my dad. As I absorbed my dad’s stories about the looting and his scramble to save the business in its aftermath, I conjured up the image of the biblical David and Goliath story. I saw my dad as Davey, the kid with slingshot and a pouch full of stones, raising his weapon against the better armed giant. I did not cast the mob of looters as the giant and instead awarded that role to the city of New York. I cannot credit an early awareness that portraying the poorest and most disenfranchised people of New York as the nine foot giant with full body armor would be a gross miscasting. I was raised on anecdotes of city government not lifting a finger to help small businesses in general and Radio Clinic in specific, but bending over backwards to help big businesses. I shared my dad’s belief in the virtue of small business and the immorality of any institution that harmed small businesses.

Standing on 98th street, about an hour into the blackout, my dad heard the plate glass window shatter, and knew there was no barrier left between the merchandise and the street. Yet, the sound of breaking glass calmed him. He never liked the glass vestibule where his dad so picturesquely fixed radios and I played video games. It took up too much floor space – and in a cramped Manhattan store, floor space is valuable. With the glass vestibule destroyed it occurred to him that he could redo the storefront however he wanted. My dad describes this realization as the point when he decided, at least on a visceral level, to keep Radio Clinic open. Not once did my dad consider closing Radio Clinic. Not when cleaning up the debris of his decimated store, not when fending off creditors and not when the city and his long-time bank refused to provide the support that the looted small businesses needed.

It was now 11 p.m., almost 2-1/2 hours into the blackout. Even though the night would result in a great deal more destruction for Radio Clinic, my dad felt he could do no more to protect the store. The owner of the pizzeria next door guarded his store with a gun and shot several times into the air to scare off looters. He offered my dad a gun. Worried that using a gun would only increase the chances of getting shot himself, he declined the offer. Fed up with both the looters and the lack of a police presence to protect his store, he headed over to the 24th police precinct on 100th street between Amsterdam and Columbus to call my mom.

My dad had been working at Radio Clinic since he was a kid and knew the local police. They were angry that one of the best stores in the neighborhood was looted. The emergency generator wasn’t working at the station, and the police were using flashlights and candles. Since batteries were in short supply at the precinct, my dad told them where they could find some in the back office at Radio Clinic. Meanwhile, he watched the police bring in looters. A few officers he knew told my dad that they “will make it rough on the bastards for you.”

My dad noticed that a lot of people brought in were bloody. He told me that he had never seen the police this outraged. “I mean, I know these guys. Many of these guys are nice and they are decent. I just remember thinking that they really didn’t care what happened to the people they were arresting.” After two hours in the station he decided it was time to head home, see his family, try to sleep and return to Radio Clinic in the morning to assess the damage. A few cops insisted on driving him to his car. The four-block drive in the undercover police car felt more dangerous to my dad than if he had walked. The crowds of looters were so thick at this point that police were using cars to chase them off the sidewalks. He sat in the passenger seat thinking the police were actually trying to hit the looters as they drove onto the sidewalks. It was a horrible ending to a horrible night.

When my dad returned Thursday morning, 11 hours into the 25-hour blackout, the streets were quiet and his store empty—empty of merchandise as well as looters. In daylight, he could see that Radio Clinic was not the only store looted. My dad first went back to the 24th precinct and asked two officers to accompany him back to Radio Clinic. One stood watch outside and the other checked for looters with my dad by flashlight. The store, while picked clean, was safe to enter. As my dad had figured, the glass vestibule in the front was destroyed and the side windows were smashed. The main floor was stripped bare of all merchandise. However, the air conditioners were still in the basement warehouse. In addition to the freight elevator, a long, steep sailor’s staircase led to the basement through a trapdoor on the floor of the office at the back of the store. The only way to safely get down these stairs was backwards and gripping the metal handrails. These stairs were so treacherous that I didn’t have the courage to use them until I was a teenager. The looters found the trapdoor and ladder, but couldn’t both climb the stairs and carry the large boxes so they left boxes of merchandise in a heap by the foot of the ladder. Even though Radio Clinic was decimated, the store still had a stockpile of air conditioners during a week where New Yorkers were desperate for them.

The thermometer continued to climb for another week and topped off at 104 degrees. New York during a heat wave emits an uncomfortable combination of exhaust fumes, hot asphalt, urine and rotting garbage. My dad knew that a heat wave this early in the summer would convince anyone who lived in an apartment that an air conditioner was necessary for survival. Looting or no, he didn’t want to squander the opportunity. Radio Clinic priced air conditioners competitively and offered delivery and installation; and my dad relied on turning air conditioner customers into regular customers. In the days that followed the looting, my dad’s only hope was to generate enough air conditioner sales to keep the business limping forward.

Surveying the wreckage on Thursday morning my dad decided he would re-open by 9am on Saturday. The store was a tremendous mess but none of the showcases or shelving was destroyed. The employees that made it through the chaotic streets and into the store felt there was nothing to do until the power was restored and wanted to head home. My dad, feeling urgent about the work that needed to occur in the next 48 hours, encouraged them to stay. He knew once the power was restored the guys in the warehouse would need to focus on a backlog of air conditioner deliveries. He wanted to prepare by moving the air conditioner and fans onto the display floor, to minimize the pressure on the warehouse. So that Thursday and Friday, several employees, my dad and my 14-year-old brother cleared the store of glass and debris and created space for the air conditioners. Then they slowly brought air conditioners and fans out of the warehouse and into the store. Since the electricity was still out, and would be until almost 10 p.m. Thursday night, they needed to improvise. Without a functioning elevator, they had to use the stairs for a trapdoor that led to the sidewalk on the 98th street side where the residential tenants accessed the building. They moved one A/C unit at a time, putting it on a dolly, wheeling it to the back of the warehouse, out a back door, up the stairs to the sidewalk, and then around the corner to Broadway and into the store.

It is not surprising to me that Radio Clinic was one of the businesses on 98th and Broadway that was looted. It had what everyone wanted: electronics. It wasn’t practical to get to midtown with its expensive merchandise. No one took the time to run fifty blocks south to steal the diamonds on 5th avenue. When the lights went out people looted where they lived and took advantage of whatever opportunity they could make. Radio Clinic, in a deteriorated section of Upper Broadway, with its stereo equipment, televisions, boom boxes and air conditioners, was an irresistible target.

While my dad and his employees were cleaning and re-stocking, neighborhood residents were streaming in, wondering if Radio Clinic planned to remain at 98th and Broadway. Although the Upper West Side was not looted to the cataclysmic proportions of the South Bronx and parts of Brooklyn, 61 stores were looted between 63rd and 100th streets: 39 on Broadway, 16 on Amsterdam and 6 on Columbus. Thirty of the 39 stores looted on Broadway were in the 90th to 110th street stretch that Radio Clinic called home. Stores had iron gates ripped off by hand, with clubs or by chains attached to cars. Twisted iron gates now pierced empty window displays. Even without coveted stereo components, Lorette Sportswear with its dismembered store mannequins, Fuller Drug Store with its empty racks and Irene’s Jewelry where the only thing that remained was a sign reading “On vacation, Back September 1st, were badly damaged. Not every business was sure they wanted to start over. The Upper West Side wasn’t exactly beleaguered, but residents of the upper reaches were shaken and anxious to see if their neighborhood would take a further beating by losing community businesses. New York’s population had been growing each decade since records were first kept in 1698, but from 1970 to 1980 a million people left, with the population falling from 8 million to 7 million. Middle class New Yorkers did not want to be left in a dying city and many had the resources to leave if that seemed like the best course of action.

My dad was trying to beat the clock to get the store ready to re-open and didn’t have the time to stop and talk to everyone that wanted to know what he planned to do. The glass was broken on the street side window, but the Broadway window was intact. He took a blank white poster used for promotions and with a thick black felt marker wrote “WE ARE STAYING” and taped it to the window.

My dad wasn’t just telling people what he thought they wanted to hear or trying to limit white flight; he truly liked the area and thought it was a great place to do business. Radio Clinic’s customers were a mix of theatrical people, blue collar workers, business people, service industry workers and housewives. He knew the customers and he knew their kids. Residents came into talk and to get restaurant recommendations. Customers transplanted from other parts of the country often told him that they never thought they would find a store in New York City that felt like their hometown. As a native New Yorker my dad knew that the city might seem like a big cold place, but every neighborhood was its own small town. After he put the sign up, people came in to thank him. They came in offering flowers and hugs. Some came in to say that they were considering leaving the neighborhood but were reassured by Radio Clinic’s decision to stay. He was amazed at its effect.

The question on everyone’s mind was who to blame for the extensive damage. Con Ed was guilty of negligence. The city was guilty of dismantling the police department because of steep budget cuts. The police themselves were guilty since when the Commissioner invoked the civil emergency plan requiring every able bodied officer to report for duty, but only 8,000 of a possible 25,000 showed up. The looters were responsible since they took advantage of the power outage. The depression level unemployment in the ghettos was responsible. Every claim was applauded by some and disputed by others. What was indisputable is that thousands of store owners saw their businesses severely damaged or completely ruined by the looting. For some it would be a knockout punch. From the sociological lens I now use to view the world, it is clear that the looters did not discriminate: first generation black-owned business, those owned by children of immigrants who cared deeply about the neighborhood where their stores had resided for decades, and unscrupulous business owners all suffered.

My dad does not share my sociological interest. His interest was pragmatic: how to save a small business.

My dad, who has always been a very quotable man, gave a comment to the press that perfectly encapsulated the situation as seen through a small business owners eyes. It must have touched a chord since the quote was picked up by local and national papers and TIME magazine. “I’m responsible for twenty-five families—the families of people that work for me. What’s going to happen to them if I pull out? As bad as I got hit, there are other guys that got wiped out. What’s going to happen if they can’t reopen? What can the city and the government do to keep people like us from leaving these neighborhoods?” My dad was under no illusions about the neighborhood. He knew Radio Clinic shared 98th street with boarded-up stores, vacant buildings, residential apartments and established businesses. He didn’t keep Radio Clinic open to avoid adding another vacant storefront to the block or with the lofty intention of anchoring the neighborhood. It was far simpler than that. Thirty-three years earlier his dad, who had run for his life from Russia, put his stake down on this block and slowly built up the business. When he was dying of cancer he passed the business on. This was his family’s business, and my dad wasn’t budging.

This is an edited chapter from a book Jen Rubin is writing about RCI/Radio Clinic and the neighborhood. If you are interested in learning more about the project or sharing your Upper West Side memories, please contact her at rubinjen@gmail.com

Thanks for this trip back in time. Great piece of history.

What a great and beautifully told story!

I was 21 and traveling in Europe when the blackout hit. The terrible stories in the international papers made me feel ashamed of NY, and of America. This story makes me feel proud of people like your Dad, and how he rallied the workers and the neighborhood.

There was no shortage of people and forces to blame for the looting, but this story shows the little bit of hope that got us through those dark times.

Webot was 11 in the Summer of ’77 vacationing with my parents in the Carolinas and also remember being embarrassed to be a New Yorker. Folks kept saying things about the looting to my parents. My would say, “well it was only in the bad areas…..” . T be honest I had no idea 61 stores on the UWS were looted. and to hear that the perps came from the neighboring SRO,, that sounds eirily like the peasant neighbors turning on the Jews in eastern europe. very scary..

and yet….I can’t seem to understand why the City politicians insist these SROs from another time cannot be converted back to their original use as Class A apartments. The world has changed and yet the market is not allowed to bring these buildings back to their original glory because of some odd wrong perception on the rose colored glory days of the 1970s.

Huh?

what didn’t you understand Sean.

Webot will be happy to explain it to you.

Great narrative. I too remember the blackout of 65, and 77. I recall how horrified I was in seeing looters smash through the Woolworth’s on 79th street.

Disgraceful.

“My dad recognized many of the early looters as guys who lived in the SRO on 305 West 98th street between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive”

Deja-vu?

My family owned Acker Merrall & Condit, the oldest wine & liquor store in America (1820). I was home watching TV when the blackout occurred. The shop was then located at 86/87th Street & Broadway, next to Perla Drugs, Tip Toe Inn & Davega Sporting Goods. I got my car out of the garage and drove the few blocks to the store (I lived at 79th & Broadway- still do). The employees were standing outside the store with the gates down. I put on my cars bright lights and pointed them at the store.

I had a weapon (legal) but never had to use it. We stayed there until the lights went back on. The store moved to 72nd Street between Broadway & Columbus 16 year’s ago when my brother bought the building. My nephew John now runs the business and AMC is the largest wine auction company in the world.

Ron–You brought back many fond memories. I never knew why AMC moved to 72nd street, but owning the building makes sense.

I was disappointed that a walk to my favorite wine store increased by seventeen blocks.

On a positive note, the move introduced my wife and me to “wine futures”. We loaded up on wine during the moving sale. As we were finishing up, the salesman suggested that the best value in the store was a case of Margaux Chateau-du-Tertre. He said not to drink it for ten years and we could return it if we did not like it. In ten years the value of a bottle increased from $15 to $60. After the long wait and tasting, futures became a frequent practice.

As Jen pointed out, part of the camaraderie of the Broadway merchants was in helping each other. My father knew them all. I purchased the first of many baseball gloves at Davega Sporting Goods since he knew the manager. Since I played a lot of sports, it was better than a candy store.

I retired to the Berkshires eight years ago and do not miss today’s retail rat race. But the joy of walking the neighborhood and talking to people is one of the few things that I will always miss.

I remember the blackout, I had to walk homefrom 116 & Broadway to 89 & Amsterdam.

It was certainly a crazy night. RCI was where my dad brought the AC for my room, and I brought my boom box. I remember AMC, I had a few friends that worked there Henry D., Bradley D. and a few others, West side camera, Berman twins all truly family owned stores. That s was what made the UWS what it truly was. now it’s chain stores that need to cover their rents by selling $5k outfits.. miss the old times

do you think the 1% could handle it?it was my 18th birthday. I could not go out for a drink.

I grew up on 99th Street around the corner from Radioclinic, we shopped there all the time (for air conditioners, of course) and I remember that blackout well. It still survives today, in an era of big box stores and on line next day delivery. Nice to hear more of the back story to the family that owns it.

I was working as a doctor at the ER in the old Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx that night. Blood was flowing in the hallways and fires were raging outside. It was one of the low points in the history of NYC. I know that this city still teeters very close to the edge of anarchy because the prevailing culture is guilty of glorifying greed and immorality.

We did not have looting after the blackout in 2003. It does not alway have to descend into anarchy.

That’s because as soon as we lost power, and the city realized it was a blackout, they dispatched the National Guard to areas that might be affected so we wouldn’t have a replay of looting and anarchy like what took place in the blackout of 1977. Looters knew there weren’t enough police in ’77, but nobody wanted to mess with the National Guard.

I remember the looting of the sobel bros. pawnshop on 89/90 & amst. they tied a chain to a car and pulled the gate down.

That photograph of the people breaking into Radio Clinic is disgusting. I wonder if any of them were identified and arrested. My guess is no.

Well it was a unique situation that night in 1977. The looters far outnumbered the police for many reason, one including city budget cut to the police. In the Ford Foundation report one officer did a nice job describing why they didn’t arrest all the looters. “The sheer numbers of people on the streets were staggering. For every store secured, two more were ripped open. For every arrest made, ten people would take the place.” Thousands of looters could be on a single street making it impossible for a squad car to get through. The police simply didn’t have the manpower to do a methodical sweep of each street. One captain explained it this way, “the whole strategy during disorders is to move men from where you don’t need them to areas where you do need them. We can get 100 to 1000 men to a trouble spot in pretty quick time. But there’s nothing you can do if it goes up everywhere at once.”

I moved to the UWS in 1977. 37 years later, I am sick about the loss of our mom and pop stores. People like your father helped make it a neighborhood. It was manageable, human size. Now all our small businesses are being driven out, not by the small looters, but by the big ones, like the Duane Reades and the CVS’s. How many of them do we need? How many do we want? Why do we no longer have any sayso about what happens in our neighborhoods. What happened to the block associations? Everyone I talk to agrees, but we can’t seem to be able to do anything about it.

37 years–The demise of the small businesses on the Upper West Side, as well as other NYC neigh borhoods, started years agao when the rents began to dramatically increase. Even very profitable small businesses cannot always survive the increase.

Thanks to all for your kind comments about RCI/Radio Clinic.

Alan

The store is STILL there, as RCI. I knew it was one of the oldest businesses on the Upper West Side but I’m amazed it’s been there since 1934. Wow! I try to buy most of my electronics there and I’m proud to say that my refrigerator was purchased there. Support local merchants!

Beautiful memories interlaced with memories of a not so beautiful episode. Nevertheless, the UWS won’t be same without RCI on the corner. I don’t know anybody in the neighborhood who didn’t buy something from RCI. The real problem is there is no cap on commercial real estate. It forces out all the small businesses, which is a shame. The UWS has become a wasteland of banks, drug stores and high-end markets. Truthfully, the UWS has lost its charm, and its bohemian-type neighborhood atmosphere. Best of luck to RCI and I wish you much success in Queens.