By Wendy Blake

At the “What Is the Object?” exhibition at the Bard Graduate Center (18 W. 86th), I was making the guard nervous. I caressed a fragile kilim prayer rug, examined a hardwood sailing-ship pulley, and stroked the fur of a top hat—all made in the 19th century. I brazenly unscrewed the top of an 18th-century Georgian glass bottle and hefted a hand ax said to be a million years old.

But the guard didn’t scold me. Visitors are meant to engage with these exquisite objects, all part of the collection of contemporary artist Richard Tuttle.

We are met with a wall of white ribbons, upon which are the words: “These are objects collected with love, amazement and need. Cared for and caring, they open doors to the world and to the self. Hold them. Feel them. Be with them.”

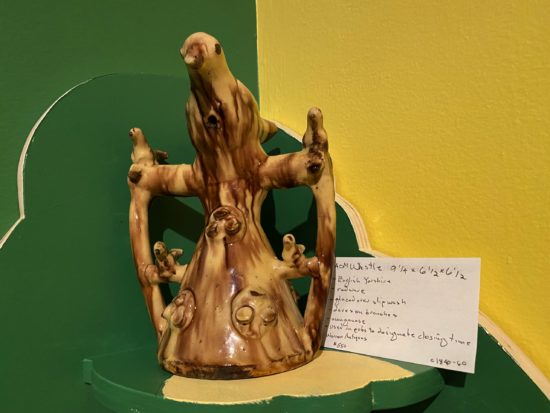

The vast majority of the 75 items are made by hand. Tuttle has grouped them together on fanciful structures he constructed himself. (Is that an ironing board or an Arp-like sculpture? We are never quite sure). His bringing together of disparate objects—of different materials, created through varying processes, from different centuries and places, with different uses—makes us want to seek a unity among them, but in this mysterious new world, attempts at sense-making are thwarted.

Each piece comes with a “biography,” a card with Tuttle’s handwritten notes. On the front, a straightforward description. On the back, tender musings about these objects that he calls his “children.” A pair of rusty hinges from New England is “sincere.” A twisted-fiber hat from the Philippines “calls to mind warblers, the forests.” He sees a “careful language” in cookie cutters made by tinkers. Woven horsehair Japanese spats have “come from a time when human and divine were one.”

Seeing the touch of the maker, of the human, is critical to Tuttle’s enterprise. Jackson Pollock is one of his favorite artists because his process is evident in his work. Then there are the imprints that speak to the effects of use, care or lack thereof, and time—worn velvet, chipped paint, mud that still clings to fabric.

Tuttle imagines how some pieces came into being, such as a “tramp box.” These were made after the Civil War from cigar boxes, possibly as therapy for “soldiers who could not re-enter society after what they ha[d] seen.” “The love dimension of this box gives hope,” he writes.

Some objects recall Tuttle’s own work. The strings of a 1940s apron hung on a wall form random squiggles. In “Ten Kinds of Memory and Memory Itself,” the artist cut lengths of string on a gallery floor, letting them fall where they would. He says, “It’s not about making something happen, but about allowing something to take place.”

Tuttle—who has worked in drawing, painting, sculpture and mixed media—says he is interested not in concepts but in such things as light and shadow, material, color, scale. And he is known for using humble materials. “I love a piece of tissue paper and I know the world doesn’t,” he says.

Indeed, his art was not always appreciated. The Whitney fired the curator of a 1975 show of his work after a scathing review by Hilton Kramer in the New York Times, who said, “It establishes new standards of lessness.” But Tuttle is now one of the 300 members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Recent small pieces of his are displayed on the first floor. In one, a fragment of fabric with fraying edges is smeared with brown; a straight pin stands at attention in it. It is quiet, fragile work. He says his work is as much about the invisible as the visible; that shadow can be seen as a “conduit to see soul”; that color is a “conduit not only reaching soul but offering soul the possibility to escape the world of black and white.”

This idea of freedom is key to his aesthetic. “I want a free space for viewer and viewed,” is printed on the gallery wall. He has created just that, as visitors, generously invited to touch these pieces, are freed from the usual constraints of the museum. More than that, he says, “The things that we engage with can “[open] regions of the self, closed off conceptually.”

When we are “free of conceptual bias,” seeing the world as it is, Tuttle says, “we will walk through the world as much better people among other people.” For him, “art is a tool for making life more available.”

Extreme close-ups in the catalogue recall the artist’s essential concerns: The woven texture of a pineapple-inspired hat, lit from within, is rendered otherworldly; folded linen collaborating with shadows becomes a mesmerizing abstraction.

The show contains some unexpected delights. A rippled burgundy scarf, for one. Apparently, Tuttle was wearing it during the installation and cast it off, making it part of the collection. Its bio says “Issey Miyake 2020.” Surprisingly, despite his passion for handmade work, he notes it is “machine woven, even more impressive than hand.” Tuttle is a contemporary artist after all.

Elsewhere, he has crumpled a piece of foil around a table leg—his almost unnoticeable, whimsical signature.

Bard Graduate Center is dedicated to the study of material culture and design history. “What is the Object?” is on display until July 10 at the gallery, at 18 W. 86th St., running concurrently with “Conserving Active Matter.”

Great article! You really make me want to see this show!