For twenty years the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group (BNHG) has promoted research and education on the history of the Bloomingdale neighborhood of New York City’s Upper West Side. Bloomingdale is the name of the neighborhood from W. 96th to W. 110th Street between Central Park and Riverside Drive. This area has been referred to as “Bloomingdale” for over 300 years.

By Pam Tice, BNHG.

This is the second of three posts on this topic. You can read Part I here.

The Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females

Since the 2013 post (linked in Part I) on the history of the organization and its homes for elderly women, the Annual Reports from 1814 to 1924 for the Association were discovered at the New York Public Library. This historical review includes several insights discovered in those reports.

The women who founded the Association were profoundly religious in their mission but were not from any particular Protestant church. In their first Annual Report their purpose is stated “God in his religious providence has reduced many respectable aged females to want. We feel it is our duty and esteem it a privilege to administer to them in comfort.” The women were the wives of merchants of the City, comfortable in their own lives. Nearly all of them were married and typically held positions on the Board. Many served for a lengthy time.

In their first three years, the Board met at the Brick Presbyterian Church on Beekman Street, and then moved to private homes until they built their first Home on 20th Street, between Second and Third Avenues, after which all meetings were held there. Until the Home opened, the women collected funds and dispersed them to worthy recipients. A Visiting Committee was charged with using “the utmost endeavor to ascertain the real character of every person they visited, closely questioning them and inquiring the surrounding neighbors.” By 1818, they were concerned that “a great number of aged poor are constantly immigrating from Europe” and made a rule that, to receive their help, someone must be a resident of New York City for three years.

By the early 1830s, the Association began a process to build an Asylum. The minister of the Church of the Ascension, then on Canal Street, preached a supportive sermon one Sunday, resulting in Mrs. Peter Stuyvesant convincing her husband to donate land on 20th Street. John Jacob Astor donated $5,000 provided the women could raise the remaining $20,000. And they did! These two leading New York City citizens gave the Association a social boost, and the Board became one that socially-connected women would spend their time.

When the Home was opened on 20th Street, daily prayer and Sunday services were an integral part of the operation. The students at the nearby Episcopal Seminary helped staff the Chapel. The Home was expanded in the 1840s, and William B. Astor contributed another $3,000. They bought land in Yorkville in the 1850s to move uptown and build a larger home, but the Civil War, followed by the 1870s recession, held back their expansion.

By the time the Association bought their land in Bloomingdale, Mrs. Edward Morgan was the “First Directress.” As the wife of ex-Senator and ex-Governor Edward Morgan, she also had the social aspects of her husband’s public life to handle. In 1877 the Morgans hosted a party at their Fifth Avenue mansion for President Rutherford Hayes.

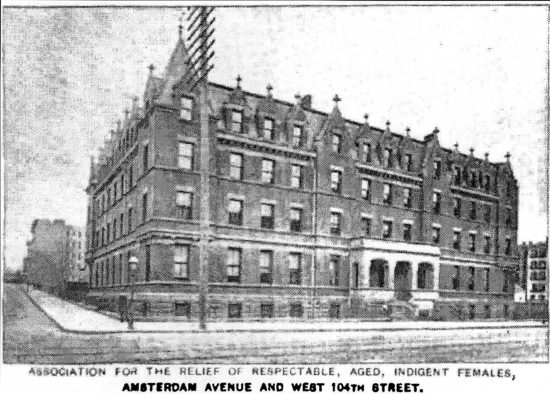

Engaging the well-established American architect Richard Morris Hunt to design their new home on Amsterdam Avenue at 104th Street gave the Association’s project the feature that has kept the building standing today. Hunt had designed an earlier version of the Asylum, when the Board thought they would be building on Fourth (Park) Avenue, but later found that the trains would be too close. When it was time to design the building for Amsterdam Avenue, Hunt may have simply dusted off his earlier plans. He was also busy then with the design of the base of the Statue of Liberty and William K. Vanderbilt’s home on Fifth Avenue. A “Committee of Gentlemen,” Headed by Edward Morgan, helped the women with their real estate dealings.

The Association’s 69th Report in 1881 has a description of the features of the Home, as designed by Hunt. The original building was in a squared “C” shape with an interior courtyard, starting at the 104th Street corner, and fronting in Amsterdam Avenue, then Tenth Avenue. (In 1907 an extension was added by Charles Rich that extended the building to 103rd Street.)

Starting at the bottom, the cellar extended under the entire building, and further extended under a portion of the sidewalk on Amsterdam Avenue. The Matron’s Room had “center speaking tubes and bells reaching to different stories and to the kitchens and laundry.” There were two large staircases and a “commodious elevator near the north staircase.”

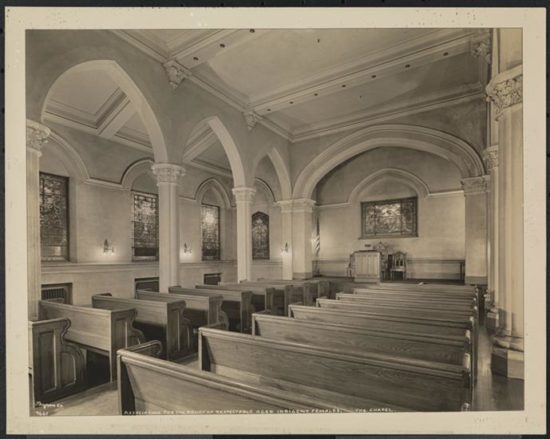

The basement had the kitchen, pantries, a laundry room, a drying room, and a linen room along with “Servants’ apartments.” There were bedrooms—doubles and singles—on every floor, linen rooms and shared bathrooms on all floors. The Board had their meeting rooms on the first floor, along with a parlor that may have served as a visitor’s room, and there was a “bright, airy chapel.”

The Association’s Meeting Minutes, in a few that are available at Columbia University’s Library, provide a glimpse of the issues the Board handled in administering the Home. In early reports, the residents are often referred to as ‘family,’ but later reports call them ‘inmates.’ The work of Board members was considerable, much more than a Board member is expected to do today. Besides constant fundraising and seeking donations of food and clothing and other items, Board members made many of the purchases for the Home. One Board member complained that the women in the Home were unhappy with the type of “porous plaster” she had purchased since they wanted a more expensive brand. Residents who mis-behaved were warned and threatened with dismissal; one woman “of intemperate habits” was dealt with. Another woman accused a nurse of stealing, using language that was “coarse and vulgar,” and had to be “severely reprimanded.”

By the 1880s, the admission fee to the Home was $150 and all property had to go to the Association; nothing could be left in a will to anyone else. Another meeting note dealt with a daughter who had removed a bank book from her mother’s room upon her death, and the Association wanted it back.

The 1908 addition to the Home was substantially funded by Olivia Sage, whose robber-baron husband Russell Sage had died and left her $75 million. Mrs. Sage, who has been written about as a “Gilded Age” woman, created a whole new identity for herself, fashioning an image of benevolence. She gave the Association $250,000. The Chapel in the new addition had Tiffany windows that honored many of the Association’s founders and activists.

The Home kept operating through the 20th century as a place for refined women to spend their final years. Sometimes written about in a New York Times obituary, or commented on in a news story about a fundraising bazaar held at the Home, they were teachers and actresses, and many were college-educated. One report mentions a vegetable garden tended by the building’s superintendent, in the rear garden. By 1930 the entrance fee was up to $1000, and applicants had to have been a resident of Manhattan or the Bronx for ten years. A 1939 Times story describes the “tenants” as coming and going as they please, shopping in the neighborhood and going to the beauty parlor. “On stormy days they played bridge in the sun room, listened to lectures or concerts, read books in the library, listened to the radio in their own rooms.” An old-fashioned clapper bell summoned them to meals.

By 1951 there was a major reorganization, and the fee changed to $70/month. Older people were living longer and their “pacts” for care the remainder of their lives were no longer financially viable. The Association limped along, one senses, during these post-war years until Federal programs—Medicare and Medicaid—came along and totally changed the game. In the mid-1960s, the Home underwent a renovation that turned old closets into space for more shared bathrooms, adding 52 to the building. At that point the name was modernized to the “Association Residence for Women, Inc.” but retained its non-profit status.

The story of saving the Association Residence from destruction is described in detail in the earlier post, so will not be repeated here.

The Home for Aged and Infirm Hebrews

Home for Aged and Infirm Hebrews, view from West 105th Street, From Jewish Home Annual Report, accessed Feb 2020.

This facility, which cared for both men and women, got its start in 1848 when Hannah Leo was called upon to visit an elderly woman of her faith and subsequently organized other women in her synagogue, B’nai Jeshurun, to help the aged and indigent women. They provided “outdoor” relief for a number of years.

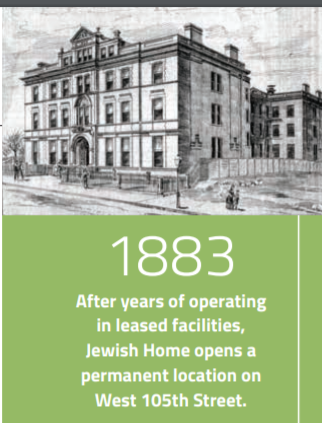

In 1866, the group was reincorporated as the B’Nai Jeshurun Ladies Benevolent Society and leased a building on West 17th Street that served as their first asylum. The group operated in leased buildings, on West 32nd Street, then Lexington Avenue at 63rd Street, and finally, by 1876, on East 86th Street in a mansion overlooking the East River. Along the way, their homes were opened to men also.

The Benevolent Society bought eight adjoining lots on West 105th and 106th Streets and built their first building, the “Home for Aged and Infirm Hebrews.” The address of the original building, dedicated on March 24, 1883, was 125 West 105th Street, located between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues. The red brick building on West 105th was connected to another on West 106th Street with a structure connecting them.

Admission to the Home did not require a fee. Applicants initially had to be 60 years or older, of good moral character and of sound mind. By the 1920s, there was accommodation for 350 people. Visitors were allowed on Thursdays, Saturdays and Sundays from 1-4 pm.

From the beginning through 1920, Dr. Simeon N. Leo, Hannah Leo’s son, served the home without pay as its physician. Every year, the Home’s Purim celebration was noted in the news, as that holiday featured bringing food to the poor. The Home was known for several innovations in the care of the elderly, including employing professional social workers, and creating individual care plans for its residents.

The Hebrew Home building was expanded numerous times over the years, until it reached the complex that we have today, now called “the New Jewish Home,” providing services to New Yorkers of all faiths and backgrounds.

Home for the Aged, Little Sisters of the Poor

The Little Sisters of the Poor established their home at 135 West 106th Street in 1883-1885, between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues, on the north side of the street. In 1894 they added to the original building, to the east, in the same style, using the same architectural firm. Their initial purchase of lots in 1883 stretched to 107th Street where they added an extension in 1912.

This was the only home where care of the aged was in the hands of a religious order, but, amazingly, those admitted did not have to be Roman Catholics. There was no fee for admission, and both men and women were accepted providing they were 60 years or older. One had to be “of good moral character.”

Little Sisters of the Poor was formed in France in 1839 in St. Servan, on the coast of Brittany, by Sister Jeanne Jugan. Members of the order made vows of chastity, poverty and obedience, but also took a vow of “hospitality.” Sister Jugan was canonized in 2009 by Pope Benedict XVI. The Sisters work spread to other countries in Europe, and in 1868 they came to the United States, to Brooklyn, and soon had a home established on DeKalb Avenue. By the 1890s they had established 39 homes across the U.S.

The Little Sisters of the Poor also came to Manhattan, first to 31st Street, and then to East 70th Street near Third Avenue. The brick home on West 106th Street was dedicated by Archbishop Corrigan on May 23, 1886, with separate male and female wings, including a chapel in the center. No information about the operation of the Home was found for this article, other than in the charity listings for New York City. One listing noted that applicants to the Home on West 106th Street must be from the west side, while the East 70th Street Home served east siders.

Residents of the Home were provided food, clothing and shelter and were supposed to be “happy” as they lived their final years. Visitors were allowed every day from 11 to 5 pm. Residents were not required to attend religious services.

One attribute that made this home different from the others in our neighborhood was that the Sisters upheld their tradition in every location by venturing forth to the community every day to “beg.” Pairs of Sisters would go out, on foot, or with a cart, to ask restaurants, hotels, private homes, butcher shops, bakeries, grocery stores and even breweries for donations of food, money, clothing, or fuel. Today’s non-profit organizations, such as City Harvest, that recycle leftover food are in this same tradition, although we don’t call their appeals “begging.”

While other Homes regularly held fundraising events, working through their Boards of Lady Managers, there were no news reports of such events for the Little Sisters. Once, however, in 1908, a charity event in a New York City hotel, held by French chefs to show their skills, benefited the Little Sisters of the Poor. They were also often named as a beneficiary of many people whose wills were printed in news reports, a popular practice in early New York.

No report of when the Home was torn down was found; however, it was listed as “active” in a 1975 guide to nursing homes. In 1978 the property was an empty lot when the West Side Federation of Supportive Senior Housing began discussions with the Little Sisters of the Poor to purchase it, which they did in 1980. The WSFSSH opened their “Red Oak” apartments, housing for low-income seniors, in 1982.

Note: the Sources used for this post will be included at the end of Part III, coming next weekend. Read other Bloomingdale history columns here.

Absolutely wonderful that you are taking the time to present

so much of New York’s history. History which is, unfortunately,

often overlooked. Keep up the good work.

Absolutely fascinating reading. Thank you so much!!!

Sounds as if all the issues of institutional housing, from the most genteel assisted living to lower rent nursing homes, are endemic through the generations: collecting the fees, communal living with rules, staffing, family tussling over property.

Nonetheless, the benefits of community and medical support outweigh the costs for most people and often for families, whose involvement can be so helpful . These early philanthropists left us handsome old buildings and histories full of lessons apt today.

Not all issues are solvable, modern or historic. But they are still real and need attention.

This is gold.

The Red Oak apartment complex is a gem, with well-maintained apartments (at 30% of income), social and community services onsite and nearby, access to hospitals, etc. It seems like a great model for other efforts.