Each month we choose an object from the N-Y Historical Society Library’s collection that relates to the history of the Upper West Side and use it as the focus of an article. The topic for this month’s column, the Lion Brewery, dovetails with the Society’s latest exhibit, Beer Here: Brewing New York’s History, a survey of the social, economic, political and technological history of the brew. Many thanks to the Society’s library staff and to Carl Miller, host of BeerHistory.com who shared information about the Lion. The brewery’s history, he says, “coincides with the Golden Age of American brewing—the 1880’s and 90’s.”

Although the Lion Brewery occupied a huge chunk of Manhattan Valley for almost 100 years—it sprawled all the way from 107th Street to 109th Street, Ninth Avenue (now Columbus Avenue) to Central Park—it’s been a bit tricky finding information on it. The questions I wanted to answer were: How and why did the brewery get built in this part of town? Who were the people behind it? What did it look like? What impact did it have on the neighborhood? And why did it close in 1944?

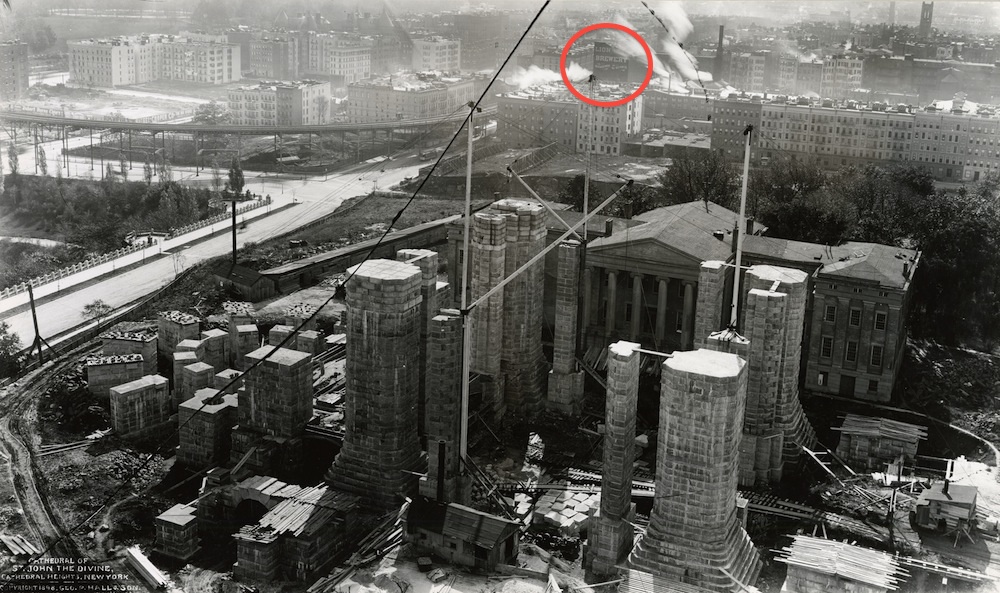

The best description of the Lion Brewery is found in a May 1879 article from a professional journal for brewers, where the author describes it as both “celebrated and extensive.” At that time it was actually called Lion Park and Brewery and included within its boundaries “a park, hotel, brewery, maltings (British speak for malt house where barley is converted to malt), ice-houses, stables, workshops and private residences.” Further on, he waxes poetic: “No wonder its sylvan shades should have become the popular resort of those who, having cast off the trammels of the old world, seek to inaugurate a brighter, better and purer one in this.” The writer of an obituary for one of the brewery’s owners, Emanuel Bernheimer, describes the “famous” park and brewery at its height of popularity: “parties are made up in all parts of the city to take the then long trip to Lion Park for an evening’s enjoyment.” In the photo from 1921 below, the brewery appears on the far left (our experts are 99% sure that’s the brewery), just off the Columbus Avenue elevated train.

Some of those who had “cast off the trammels of the old world” to come to the brewery were the people who came from Germany to work there, immigrants who were, for the most part, observant Catholics. When they first arrived, they celebrated mass in a brewery building but, as they settled into the neighborhood, they wanted their own church. In 1895 they helped build Ascension Church, just west of the brewery. Ascension is still an active part of the life of the Upper West Side, serving a variety of Americans and recent immigrants.

The spot where the brewery was built is a genuinely historic one—it is where the British forces under Lord Cornwallis and Sir William Howe established themselves in 1776 after having landed on the East Side and marching across the island. It is from this site that the British engaged in a number of small but significant skirmishes with George Washington’s troops who were occupying Harlem Heights.

The founders of the brewery chose this particular piece of land for a number of reasons. Since colonial times, New Yorkers had been drinking English-style beer, and as the city’s water quality deteriorated so did the taste of its beer. In the 1850’s, when the Croton Aqueduct was completed, much purer water flowed into the city from upstate and the prospects for beer improved enormously. At the same time, there was plenty of land to be had at a reasonable price in what is now Manhattan Valley. The area had not yet attracted the wealthy who were discouraged by its distance from the downtown center of the city and who probably didn’t want as neighbors some of the residents of two large institutions in the area—the Leake and Watts orphanage and the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum. To quote the brewer’s journal once again: Lion Park flourished in vernal loveliness when its world renowned neighbor which is now Central Park was a “howling wilderness.”

The founders of the brewery chose this particular piece of land for a number of reasons. Since colonial times, New Yorkers had been drinking English-style beer, and as the city’s water quality deteriorated so did the taste of its beer. In the 1850’s, when the Croton Aqueduct was completed, much purer water flowed into the city from upstate and the prospects for beer improved enormously. At the same time, there was plenty of land to be had at a reasonable price in what is now Manhattan Valley. The area had not yet attracted the wealthy who were discouraged by its distance from the downtown center of the city and who probably didn’t want as neighbors some of the residents of two large institutions in the area—the Leake and Watts orphanage and the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum. To quote the brewer’s journal once again: Lion Park flourished in vernal loveliness when its world renowned neighbor which is now Central Park was a “howling wilderness.”

So it was in 1858 that two brothers, Albert and James Speyers, chose this piece of the Upper West Side to build their brewery. Sadly, just one year later, what they had built was almost entirely destroyed by fire. But the resilient Speyers brothers rebuilt immediately. Shortly after, in 1864, when Albert retired, Emmanuel Bernheimer became a partner in the operation. The name of the firm was changed to Speyers and Bernheimer, and new buildings were added. When James retired in 1863, Augustus Schmid joined Bernheimer. Under the stewardship of Bernheimer and Schmid, the Lion Brewery achieved “its principal triumphs” according to the journal. It became, with its “tremendous capacity, second to few in the United States.”

Bernheimer and Schmid were interesting men of their time. Accounts of their lives detailed in their obituaries give us an idea of what they were like and, by extension, what doing business in the 19th century was like.

Augustus Schmid was born in 1803 in the principality of Hechingen-Hohenzollern a principality in what is now Germany. When he was ten, he left school and undertook an apprenticeship in brewing. At 17 he became a journeyman at a brewery in a nearby town. From there he went on to work in a number of breweries and in 1827, just three days after he married, he took charge of a brewery at Constanz, located on the lake of the same name. At Constanz his “endeavors were crowned with prosperity.”

As Schmid prospered, he became an influential citizen and a member of the city council. Then came the European revolution of 1848. The anti-authoritarian side he had chosen was defeated and he fled “with his liberal-minded compatriots” across the border to Switzerland. Denied German citizenship, he worked in the brewing business in Zurich and in 1850 decided to try his luck in the New World. He wasted no time establishing a brewery on 4th Street near Avenue B, resurrected the name Constanz Brewery, and once again prospered by brewing lagered beer, the favorite of his fellow immigrants.

Seeing “how little harmony existed among the brewers of that day,” he called a meeting of all New York brewers who subsequently formed an association and drew up a constitution. When the government imposed a duty on beer to help finance the Civil War, the newly formed Brewers Union called a meeting and Schmid acted as chairman. In his later years, he retired from business and lived “in his beautiful [sic]situated villa where he enjoyed an undisturbed domestic happiness.”

Schmid’s partner, Emanuel Bernheimer was born in Germany in 1817 and served an apprenticeship there before coming to New York in 1844. He arrived “with some capital” and set up an importing business on Beaver Street. In 1850, he became a partner of August Schmid in the Constanz Brewery which is described as “successful beyond the hopes of the partners.” In all, at its height, the firm of Bernheimer and Schmid owned and operated five breweries, including the Lion, on Staten Island and in Manhattan.

Bernheimer’s genius seems to have been advertising. He began an elaborate system of marketing which was quickly adopted by his fellow brewers and he established “beer saloons of his own in various parts of the city, gradually disposing of them to their lessees,” not unlike the franchise system of today. The advertisement shown at left (click to enlarge) is a perfect example of business savvy combined with some of the higher ideals of the day: “Kings and Emperors will gladly lay down their arms of warfare and drink to the health and happiness of all their peoples. The sun of that golden morn will soon rise and all nationalities will be found drinking our Pilsener and Wuerzberger – the beer of Surpassing quality and lasting flavor.” An image of 19th century paradise accompanied by a glass of Lion Brewery beer. Perfect.

Bernheimer’s genius seems to have been advertising. He began an elaborate system of marketing which was quickly adopted by his fellow brewers and he established “beer saloons of his own in various parts of the city, gradually disposing of them to their lessees,” not unlike the franchise system of today. The advertisement shown at left (click to enlarge) is a perfect example of business savvy combined with some of the higher ideals of the day: “Kings and Emperors will gladly lay down their arms of warfare and drink to the health and happiness of all their peoples. The sun of that golden morn will soon rise and all nationalities will be found drinking our Pilsener and Wuerzberger – the beer of Surpassing quality and lasting flavor.” An image of 19th century paradise accompanied by a glass of Lion Brewery beer. Perfect.

According to his obituary, Bernheimer was a lifelong Democrat but “in local politics he was disposed to be independent.” He was one of the oldest members of the Temple Emanu-El and a contributor to the German Widows and Orphans’ Society, Mount Sinai Hospital, the German Hospital and the Montefiore Home for Chronic Invalids.

If the mid and late 1800’s were glory days for the brewing industry in the city, the beginning of the 20th century saw its decline. The anti-saloon movement and then Prohibition dealt a heavy then fatal blow to the industry in New York. The situation led to the mergers of many of the city’s breweries, including the Lion, which was acquired by the Greater New York Brewery, Inc. In 1942 it was closed down, and in August of 1943 everything was auctioned off. A flier advertising the auction lists stainless steel can fillers; soaking, washing and rinsing units; and copper brew kettles, among other things. The plant was torn down in 1944 – more than 3,000 tons of steel were taken away and recycled for the war effort. Curtain down on the brewery’s vision of “the spirit of Peace.”

Below, check out another photo of the brewery in the background of an amazing shot of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine being built in 1898.

Photos and images courtesy of the New-York Historical Society. Image of advertisement from Carl Miller.

To read the other articles in this series, click here.

Enjoyed this article immensely and found it very informative !

I worked on the reconstruction of Columbus Avenue in the 1990’s. During the excavation of the road we uncovered a large underground cavern made of brick arches on Columbus between 107 and 108. It was magnificent in its architecture. I see from reading your peace that it was part of the Lion Brewery. Can you tell me how they used the structure? Do you have drawings or photos?

Enjoyed the article! I have a beer barrel that has this name on it, so was curious about some info on it. Thank you.

found glass bottle by my house from lion brewery wanted to know if anybody has a interested in it

Just a little history of Lion Brewery. I was born in Feb/1945 @ 973 Columbus Ave.(Across from the remains of the brewery. A correction should be made in your Data that houses weren’t built on the site but a Public JR. High School was (P.S.54): It’s still there.