By Bonnie Eissner

Nearly 250 years ago, Thomas Jefferson wrote (and Benjamin Franklin edited) one of the most famous sentences in the English language — the one that begins “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”

With these words and just over 1,400 others — equivalent to one long or two shorter West Side Rag stories — Jefferson and his fellow members of the Second Continental Congress set the 13 British colonies in America on the path to war and ultimately nationhood.

But what ideas and events seeded this rebellion? And how did its leaders rally people, who were divided and often doubtful, to the cause?

Those questions are addressed in “Declaring the Revolution: America’s Printed Path to Independence,” The New York Historical’s just-opened exhibit featuring about 60 documents from the collection of David M. Rubenstein, co-chairman of the Carlyle Group private equity firm.

The show, which narrates the build-up to war and the waging of it, is a kind of appetizer for the feast of celebrations to come in 2026, when the United States honors its semiquincentennial. It feels especially timely, coming as daily headlines warn of new challenges to the nation’s democratic principles.

The exhibit begins with the origin story of the Declaration of Independence, tracing its tenets to the Magna Carta — of which there’s a 1773 engraving — and the 1689 English Bill of Rights, shown here in a first edition.

“The reason why there was such a thing as an American Revolution,” curator Mazy Boroujerdi told West Side Rag, “is because Americans at the time considered themselves to be British. In other words, you had a mother country, a parent country, that was, in a way, disenfranchising individuals who thought that they were participants in Britishness or Englishness.”

The widening schism between the colonists and the crown is conveyed in other pivotal documents such as the Stamp Act of 1765, the detested first direct tax on the colonies, which was eventually repealed. A broadside on display details the “bloody butchery” by British troops at the 1775 Battle of Lexington and Concord.

The exhibition also depicts the slog of war through plans, campaigns, orations, and images, including an apocryphal one of a resolute George Washington in 1780 holding a copy of the Declaration of Independence as his horse is tended to by his enslaved groomsman.

Here are some of the highlights from the museum’s exhibition, which runs through April 12.

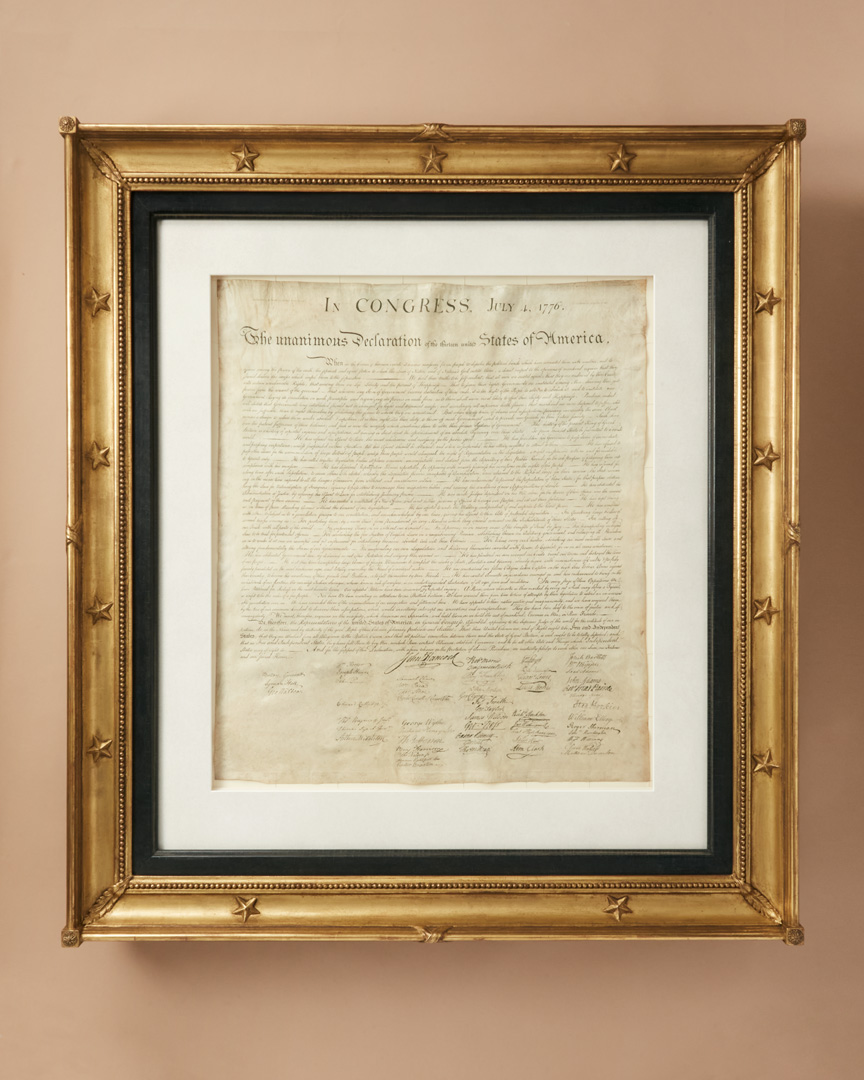

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence replicated in history books is not the original manuscript. That was lost. Rather, the version with the 56 signatures is a handwritten and enlarged vellum document from August 2, 1776. That one is on display at the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C.

The one currently on view at New York Historical is an official engraving from 1823, authorized by then-Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. The 1823 engraving is prized, curator Boroujerdi said, because it more closely resembles what the document looked like in 1776 than the faint and barely decipherable version in the National Archives. Mounted in a gold-colored frame, the document is the show’s centerpiece. The preamble and the celebrated statement of human rights are easy to read. The signatures, with their iconic flourishes, stand out and add flair and humanity to the document. They prompt contemplations about the men who shaped and signed the declaration. Most of them owned slaves; six later signed the Constitution.

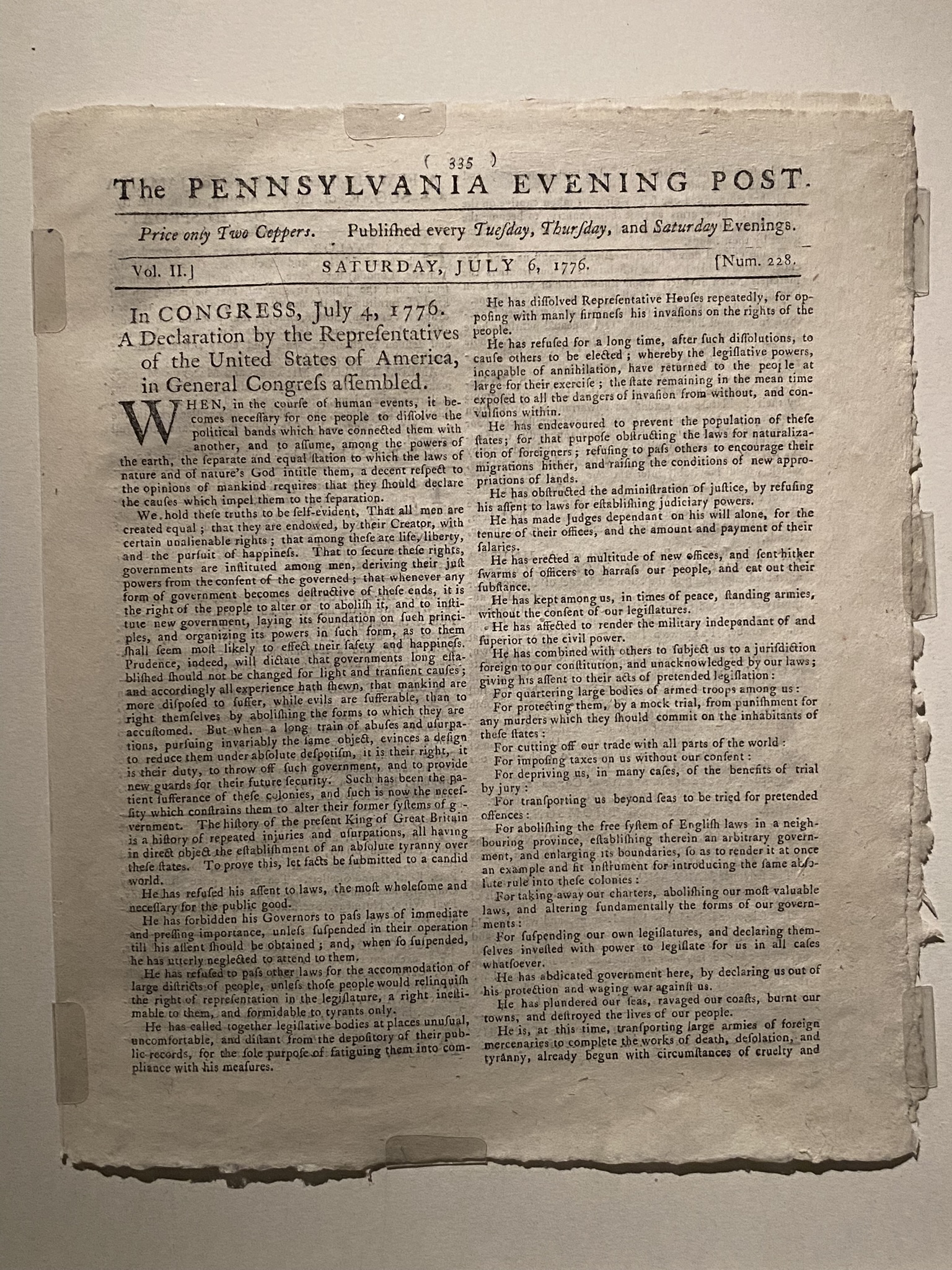

The First Widely Distributed Declaration of Independence

On the evening of Thursday, July 4, 1776, the now-lost manuscript version of the Declaration of Independence was brought to a Philadelphia printer, who produced the text as a broadside, which was sent to select government and military leaders. The local Pennsylvania Evening Post obtained a copy on July 5 and, because the paper was a triweekly with a Saturday edition, published the declaration on July 6, scooping the competition. The document lists 27 grievances against King George III, which include “He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.” This printed version from the Evening Post is easier to read than the script engraving. Even skimming the dramatically worded complaints evokes parallels to the present.

“Common Sense” by Thomas Paine

Printed in the last six months before the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Paine’s widely circulated pamphlet “Common Sense” rails against the king, who “hath shown himself such an inveterate enemy to liberty, and discovered such a thirst for arbitrary power.” The pamphlet, with its colorful prose, including allusions to the colonists as slaves of the crown, helped to sour colonists on their monarch and gave Jefferson and his fellow declaration writers grist for the grievances they enumerated. Paine’s “no kings” stance feels eerily resonant today.

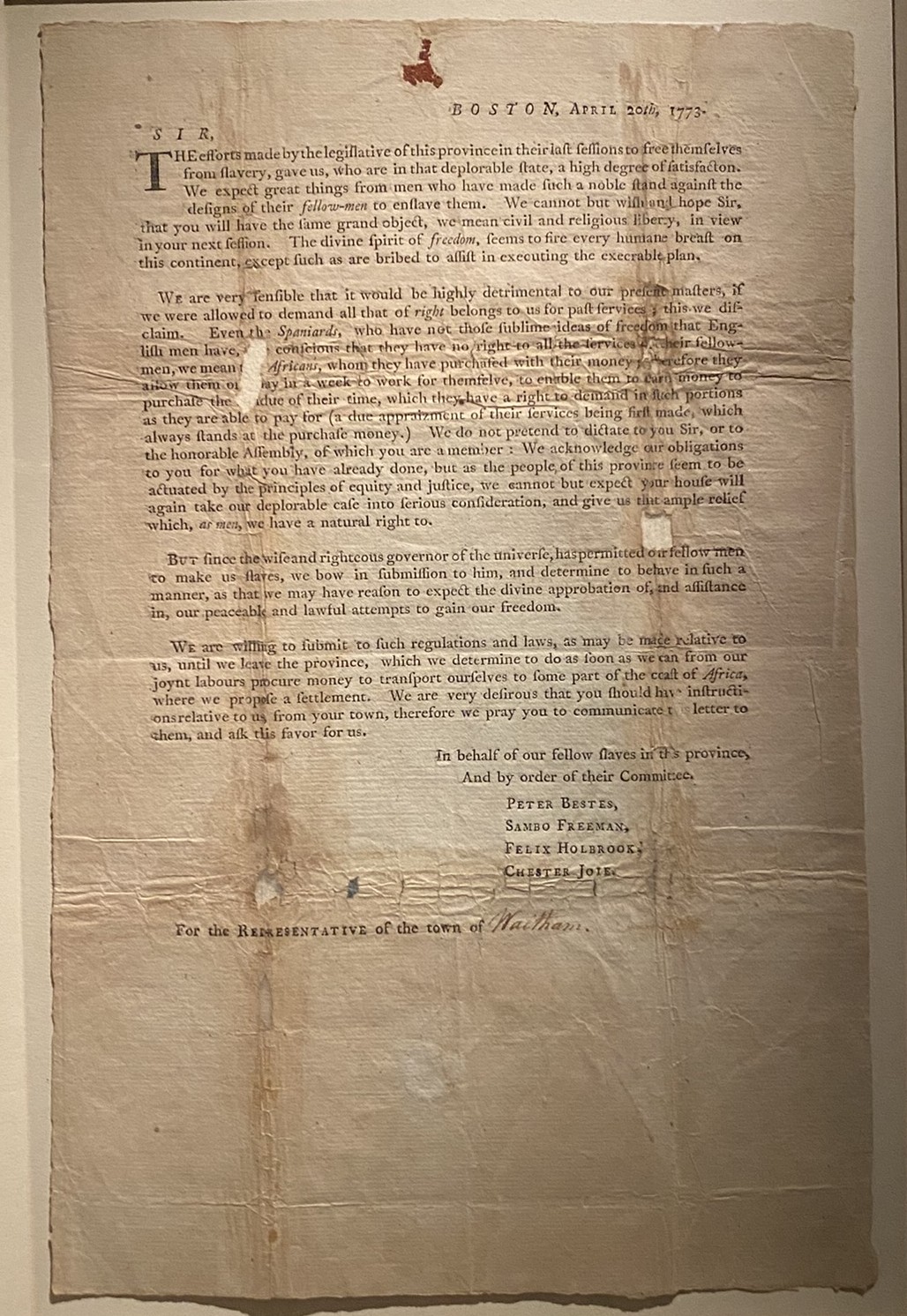

A Slave Petition for Freedom

Next to the two versions of the Declaration of Independence hangs a broadside — a printed piece of paper — engraved by four slaves in Boston petitioning for their freedom. Three years before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the enslaved men modestly proposed to a legislator in the state’s General Court that individuals in bondage be permitted one day a week to work for themselves to purchase their freedom. Poignantly, the authors co-opted the cries of enslavement that the colonists leveled against Britain. “We expect great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them,” they wrote. The eloquent petition points to the hypocrisy inherent in white colonists demanding their freedom while hundreds of thousands of Black people were held in bondage.

The Boston Massacre

Perhaps even more than his midnight ride, which Henry Wadsworth Longfellow exaggerated, Boston goldsmith Paul Revere bolstered the revolutionary cause with this embellished depiction of what was dubbed “The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street.” Revere based the colored print on a drawing by Henry Pelham, adding his own touches, and circulated it quickly. It depicts a line of redcoats in front of the British-guarded Custom House firing into a crowd of unarmed colonists, some of whom fall to the ground, spurting blood. The reality was far different. “The whole thing was a melee — massively disorganized, complete chaos,” Boroujerdi said. The clash on March 5, 1770, started with an altercation between a teenager and a British sentry, which drew a mob of hundreds. Eight soldiers came to the sentry’s aid. Hemmed in and pelted with objects, the soldiers fired into the crowd, killing five. Revere leveraged the event to sow resentment of the British and their occupying forces. The rest, as they say, is history.

The New York Historical, at 170 Central Park West (77th Street), is open Tuesday through Sunday, with pay-as-you-wish admission from 5 to 8 p.m. on Fridays.

Fascinating

No kings indeed!

Is this at the NY Historical Society?

yes

There is nothing “eerily resonant” in No Kings. That document actually was a political and philosophical document directly addressing a very real system and set of circumstances. No Kings today is a histrionic nonsensical slogan based solely in the minds of some very fragile, emotionally unstable people who could never have engaged in the intellectual discourse or the courage that was required of the men who built this country.

“No Kings today is a histrionic nonsensical slogan ….” sorta like MAGA?

thumb down

While the two share some surface-level similarities, the differences are far more substantial. You’re right that “no kings” functions mostly as a catchy slogan, one that few people pause long enough to actually unpack. Most importantly, Paine articulated a coherent political philosophy and a concrete alternative to the system he opposed. In contrast, the modern “no kings” sentiment is diffuse, unfocused, and largely devoid of any intellectual grounding that gave Common Sense its power.

Many, many of us rightfully believe that the current Commander In Chief has exceeded his constitutional granted authority, breaking the guardrails of the office that have been in place both legally and historically. “No Kings” is an appropriate public reaction to this overstep of executive authority. It’s kind of funny, you calling others fragile when you seem particularly triggered by the phrase.

Jill Lepore has a really interesting article in this week’s New Yorker about the issues coming up in commemorating the 250th, given the political situation, and how many different organizations (especially museums) are addressing it. Or choosing not to address it.

Here: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/11/17/what-was-the-american-revolution-for