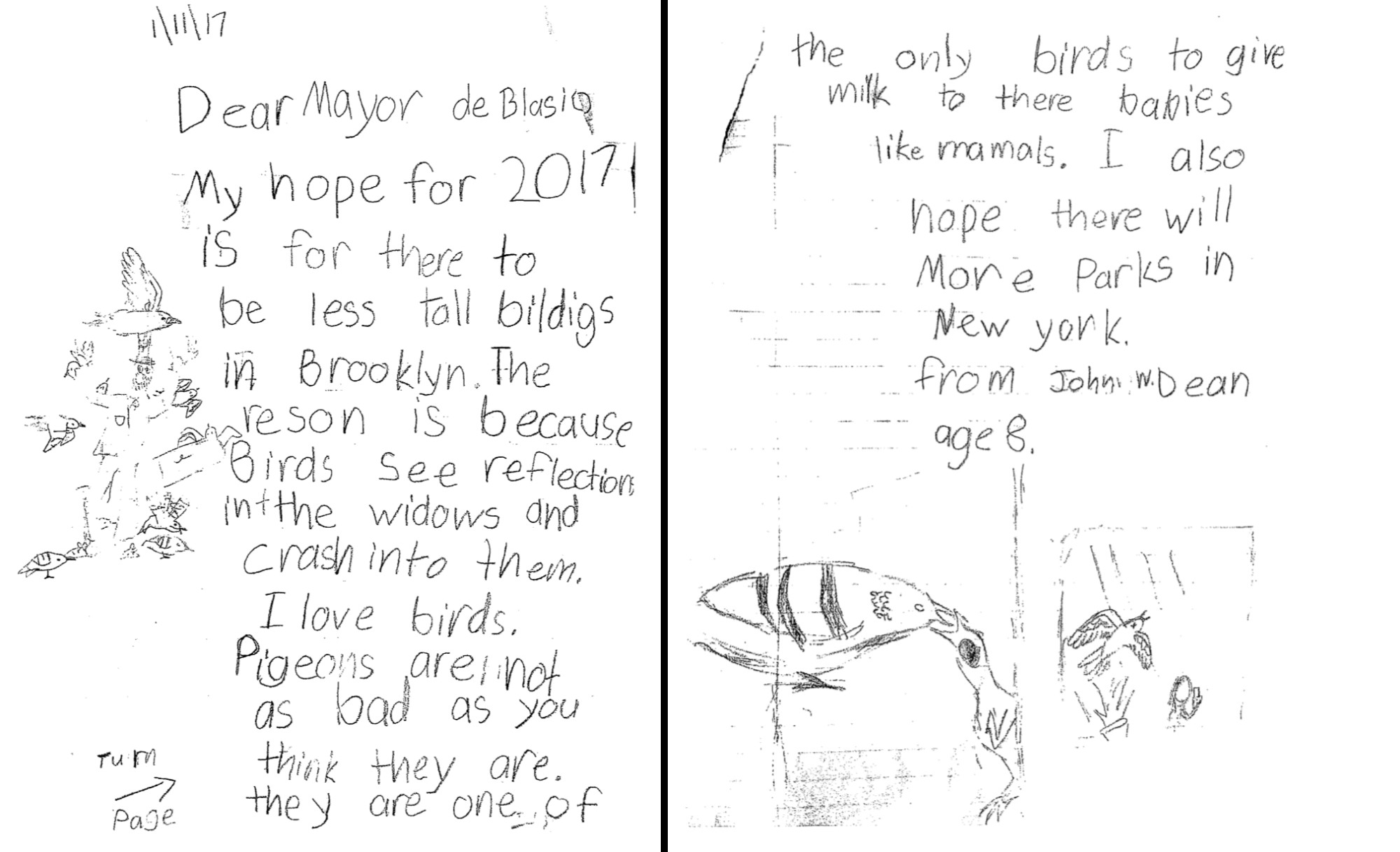

A hungry red-tailed hawk patiently waits for prey at the Circa Central Park. Many birds have crashed into the windows there. Photo by Terence Zahner.

By Alex Israel

Thirty-eight residences rise above the northwest end of Central Park, glimmering and gleaming and advertising a panorama of views “as magical as the changing seasons.” At 285 West 110th Street, “every home is a luxurious new interpretation of West Side living.” Unless, that is, you are one of the two million migratory birds that pass through New York during spring and fall. For those birds, the magic of the changing seasons may be cut short by the glass of a building that injures—and more frequently kills—them upon impact.

Circa Central Park, a luxury condominium building managed by Corcoran, developed by Artimus Construction, and designed by FXCollaborative (none of which responded to requests for comment on this article), opened at Frederick Douglass Circle in 2017. The building has received numerous awards in its two years of operation, as well as distinctions from local press (The Wall Street Journal called it “a study in modernism.”) It has also gotten numerous complaints from bird enthusiasts who say they have found nearly 200 dead and injured birds surrounding its perimeter in that same two-year period.

FXCollaborative, a renowned architectural firm, approached designing the residence with sustainable practices in mind. The “environmentally-responsive skin” of the building, which incorporates large expanses of glass combined with discrete shading elements to temper unwanted glare and heat gain, “reduc[es] the need for energy-intensive mechanical air conditioning,” according to their website. Unfortunately, while the glass may have a positive impact on resource management, it has an adverse effect on migratory birds.

Building glass is one of two major hurdles for approximately one hundred species of birds that traverse the Atlantic Flyway headed north in the spring and south in the fall. Reflective glass confuses birds—especially when situated near parks—as they mistake what they see in the reflection (e.g. trees and sky) for the real thing and fly towards it. Clear glass can be an issue too; with appealing foliage behind it, the birds may head towards it in search of shelter or food. The other hurdle is light pollution, which draws birds in during their nighttime migration and disorients them, making them even more prone to collisions.

Harlem resident, birder, and photographer Terence Zahner has regularly monitored the perimeter of Circa Central Park during the migration season, documenting the dead and injured birds he finds. The same practice is carried out on a larger scale by NYC Audubon through a volunteer program called Project Safe Flight (for which this writer volunteers)—but Circa Central Park is not part of an official Project Safe Flight route, so Zahner is on his own.

When I walked out of the apartment this morning I thought “how many window collision victims am I prepared to deal with?”. Welp, I’ve found 16 already 🤯 @ABCbirds @NYCAudubon @NYCSpeakerCoJo @RLEspinal #bird #birding pic.twitter.com/mLEDZYz21Y

— terence zahner (@ZahnerPhoto) November 2, 2019

In more than two years of near-daily data collection at Circa, Zahner says he has counted upwards of 138 dead and decomposing birds and 38 injured birds, across thirty different species. The most in a single day was sixteen, which included birds that died inside the building’s interior courtyard (which he referred to as a “death trap”).

And that’s just one building. NYC Audubon estimates between 90,000 and 230,000 birds die while flying through the five boroughs every year, spanning at least a hundred species.

“You talk to the building staff, and they’re like ‘oh, yeah, we pick these up every day,'” Zahner said during an interview with WSR, after a late-season, early-morning walk. “There’s no way that they haven’t all encountered a dead bird at some point.”

Zahner transports any injured birds he finds to the Upper West Side’s own Wild Bird Fund, located at 565 Columbus Ave (between 87th and 88th Streets). “In some ways, it’s fortunate to be so close to them,” he said. The sooner they can be treated, the better chance they have of survival.

Social media has become a huge asset in spreading awareness about the issue, Zahner said. Repeated exposure provides an opportunity to compel local residents—but also problematic buildings and elected officials—to confront the problem.

“A lot of the species that are impacted people have never seen,” he said. “I need to photograph this in a way that someone who has no idea what this bird is gets an in-your-face view of it,” he explained.

While some people might be uncomfortable with a constant slew of dead and injured bird imagery, “This is a problem that everyone needs to be aware of,” Zahner said. “If you just ignore it, it’s going to keep happening, and nothing’s going to get done.”

In addition to sharing his data with Circa and its staff, Zahner used it as the basis for testimony in support of a City Council bill that would help make the skies and streets safer for birds.

Int. 1482-2019, “The Bird Friendly Glass Bill,” would require that glass installed on newly constructed or altered buildings be treated to reduce bird strike fatalities. Now sponsored by 20 city council members, including Bill Perkins (responsible for District 9, which covers Circa), Int. 1482-2019 is currently “laid over” in the Committee on Housing and Buildings—meaning a vote was postponed indefinitely as the committee reviews the testimony from the hearing.

If passed, the bill would amend the New York City building code to require bird-friendly glass be used for ninety percent of glass on the lowest 75 feet of a building, and on the 12 feet above any green roof system. Intentionally minimizing the use of glass, placing glass behind some kind of screening, and selecting glass with inherent collision-reducing properties (like fritted patterns and frosting) during a building’s development are all widely accepted strategies for bird-friendly design.

But existing buildings that don’t incorporate these strategies wouldn’t necessarily need structural change to meet the requirements. They could treat their current glass to reduce window strikes by adding a “visual noise” that the birds can perceive, such as paint, tape, or decals. In either case, the amendment would not apply retroactively.

“Developers and building owners are currently free to completely ignore bird deaths, as the owners of Circa Central Park have done, despite receiving all the data I have collected and being well aware of the problem,” wrote Zahner in his statement to the council. “Without statutory requirements, profits will always win over environmental conservation issues.”

Representatives from bird-related organizations, including the Wild Bird Fund—the city’s only wildlife rehabilitation facility—testified in support of the bill. WBF Director Rita McMahon educated the committee on the many hundreds of window-strike victims the clinic treats every season, suffering from concussions, broken beaks, broken wings, internal injuries, eye damage and many other traumas.

“After successfully flying thousands of miles, a bird strikes the glass and then falls to the pavement below sometimes 10, 20, 30 stories down to the sidewalk. At best, one-third survive,” she said. Following the hearing, Wild Bird Fund released data that maps the clinic’s window-strike patients back five years, which you can explore below.

Representatives from various design and architectural institutions, including FXCollaborative—the group that designed Circa—also shared statements of support of Int. 1482-2019 during the hearing.

FXCollaborative’s Director of Sustainability, Dan Piselli, endorsed the bill on behalf of the American Institute of Architects New York. “As architects, we often use glass to connect people with nature, but if done wrong, that glass can literally kill the nature we seek to connect with,” he wrote in his statement.

Piselli cited The Javits Center, the Statue of Liberty Museum, and the Columbia University School of Nursing as examples of institutional projects that have successfully implemented bird-safe solutions.

“While we’ve had success implementing bird-safe glass with institutional clients, we’ve had less success with commercial building owners,” he said. “As a result, we have built very few commercial buildings with bird-safe features in NYC. Unfortunately, one residential building we designed currently has a big bird collision problem. Most building owners will not do this on their own, and that is why legislation is necessary.”

Testimony opposed to Int. 1482-2019, though scarce, seemed to support Piselli’s hypothesis. Representatives from several real estate and building management groups suggested the city hold off on passing the citywide bill, and instead wait for recommendations from a Bird-friendly Building Council—a hypothetical advisory group proposed in a separate New York State Senate bill (A4055B) that was vetoed by Governor Cuomo on November 20.

Delaying action could mean another brutal season ahead. This spring, thousands will make their way through New York, starting the cycle of death all over again.

“When people are made aware of the consequences of poorly designed, glass-windowed buildings, they care and want to see change,” said a high school junior at the hearing—displaying more than 170 signatures he had gathered from classmates in support of the bill.

“Birds mean a lot to me, and my interest in them has made my life better,” he said, speaking on behalf of generations of birders before him. “Now is my time to give back to them.”

This is the fourth installation of ‘The Bird Bulletin,’ a recurring series featuring topics about birds and the people who love, chase, and help them on the Upper West Side.

Bravo! I love this work. They need to figure out how to change this. Unfair to these birds. Would love to help

You’ve got to be kidding me.

Did you know that the vast majority of bird deaths are from flying into buildings that are 1 to 3 stories tall?

I’m sure the occupants of the buildings would love to have stickers placed on their windows which would interfere with their views and their ability to clean their windows even thought there is a minuscule possibility of having a bird strike.

The aggressive birds that die attacking their reflections in the windows of larger Manhattan buildings probably will just die anyway in the next suburban community by flying into the window of a one story home.

Although I’m sure that there are many, I can’t say that I’ve ever seen a bird death on the streets of Manhattan in the past 30 years – other than pigeons being run over by cars. In the suburbs I have seen many.

Pass the law all ready would be great for our feathered friends