By Nancy Novick

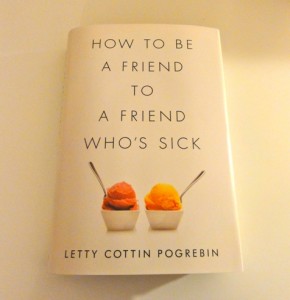

Letty Cottin Pogrebin advocates telling the truth, which is why I’d like to share my first impression of her new book “How to be a Friend to a Friend Who’s Sick”: What a good idea for a magazine article. How, I wondered, could even this accomplished author, activist, and speaker—whose pedigree includes serving as founding editor of Ms. magazine and past president of the Author’s Guild—fill an entire book on this subject?

It turns out she not only could, but has, in a way that is informative, revealing, compassionate, and useful.

Prompted by her diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer, Ms. Pogrebin’s book is filled with her insights, as well as stories and advice from friends and fellow patients, on how we can be most helpful to those we care about when illness strikes.

Prompted by her diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer, Ms. Pogrebin’s book is filled with her insights, as well as stories and advice from friends and fellow patients, on how we can be most helpful to those we care about when illness strikes.

While some of the information in How to Be A Friend initially seems to be “just common sense,” Ms. Pogrebin illuminates the foundations for these suggestions — for example, why certain language is helpful or hurtful. Other passages cover content this reviewer had not considered at all, such as how to respond to friends whose illnesses are related to, and exacerbated by, financial troubles. Clear chapter headings also make the book a useful reference for specific topics such as “Sickness and Shame” and “Dealing with Dementia”

More general tips include allowing the gravity of the friend’s illness to guide the nature of a visit. A person who is in pain may not be able to answer questions but will likely value silent companionship, while a friend who is less debilitated may be eager to recount the details of his or her condition to a receptive listener. Acceptance of the nature of chronic illness, and sensitivity to the desire of those who are expected to recover to discuss subjects other than their illness are also discussed.

Information is provided on how to be an advocate for your friend in the doctor’s office, on how long to visit and what to bring, how you can help family members, and what not to say to the ailing person (hint: “Oh my God” and “You look great” are not helpful). Readers are encouraged to “be sincere in your offer [of help], and ready to take no for an answer” if the patient doesn’t want what’s offered. Perhaps most important of all, Ms. Pogrebin advises, give your sick friend permission to tell the truth about what they need and free them from the need to take care of you.

What’s missing from the book may be what’s missing from our healthcare system—clear direction on how to be an advocate for a sick friend while they are in the hospital if they are receiving inadequate or inappropriate care or treatment. How to help make sure that enough attention is paid. Ms. Pogrebin acknowledges the exceptionally positive nature of her experience with caregivers at Memorial Sloan- Kettering. Many readers may have less uplifting stories of friends and family whose treatment at hospitals of all kinds was far from optimal, but perhaps this is a subject for another project.

Readers who will benefit most from this book may be those of us over 40, whose circle of friends (and relatives) have started developing the maladies that flesh is heir to. But Ms. Pogrebin does not neglect the very difficult job of being friends to young people who are sick and to attending to friends who are the caregivers for critically ill young children. This section includes valuable information on how to help a child be a good friend to a peer who is sick.

“How to be a Friend to A Friend Who’s Sick” ends with a discussion of what Ms. Pogrebin calls collective caring. While acknowledging the role of traditional support groups—and noting both their potential to help, as well as their downside—listening to the concerns and anxieties of those with more serious illness can be depressing and frightening, the author focuses on groups of people who come together with no other bond than a desire to help the friend they have in common. By planning a coordinated schedule of regular meal deliveries, company on trips to the doctor or for chemotherapy, and regular home visits, these groups demonstrate their friendship in ways that are generous, heartfelt and effective. Models of how to form such a group or network are included, as is an impressive list of print and on-line resources and recommended reading for caregivers.

How to Be a Friend to A Friend Who’s Sick by Letty Cottin Pogrebin is published by PublicAffairs.

Ms. Pogrebin will be interviewed by her daughter, author Abigail Pogrebin, on Wednesday, May 22nd at 7:30 pm at the JCC in Manhattan. More information is available here: https://www.jccmanhattan.org/what-everyones-talking-about?page=cat-content&progID=26538

Nancy Novick blogs about books, bookstores, and libraries at Stacked-NYC.com.

Being a patient advocate does indeed require its own book or course. First, not all friends or family members are suited for this role, despite their desire to help and/or being the only person available for the job.

It requires attention to detail, exceptional listening skills, patience, persistence, a cool, calm approach but also someone who is unafraid to ask questions (politely), of anyone and everyone who provides care, whether doctor, nurse, or other hospital staff. And someone who is not afraid to say: There’s a problem here and it needs XYZ…”

A lot of people are uncomfortable asking questions or in doing what they view as “challenging” medical care or physicians. They are just too intimidated, which is unfortunate for those who only have such folks around to “help.”

If nothing else, showing up and asking questions about treatment, etc. shows there is a family/friends and the hospital and staff WILL be held accountable (Yes, it’s true. You DO get a different level of care not only based on your fiscal resources and connections, but also on whether you are perceived as being “valued” by having friends and family show up.

EVERYONE who enters a hopsital needs their own personal, independent patient advocate (and we are NOT talking about the patient advocates on hospital staffs, who are PAID by the hospital and thus accountable to it, and who generally speaking are only present to ensure that you have insurance, etc. It’s a rare one who is actually advocating treatment and care on behalf of the individual. And if you think nurses are afraid of doctors, consider the role of the advocate, who may or may not even have any healthcare credentials akin to a nurse, although some are nurses.)

I was interested in this book and after reading the review do want to read it.

Thanks.

Jeannette,

You make many important points about what every hospitalized patient needs, and about the difference between a personal patient advocate and those on hospital staff. Thanks for your thoughtful response.