By Daniel Katzive

In the autumn of 2001, not long after the attack on the World Trade Center, Len Zimmerman was biking along the Hudson River when he made an interesting discovery. “All of a sudden, there’s this pier that’s opened up,” he recalls.

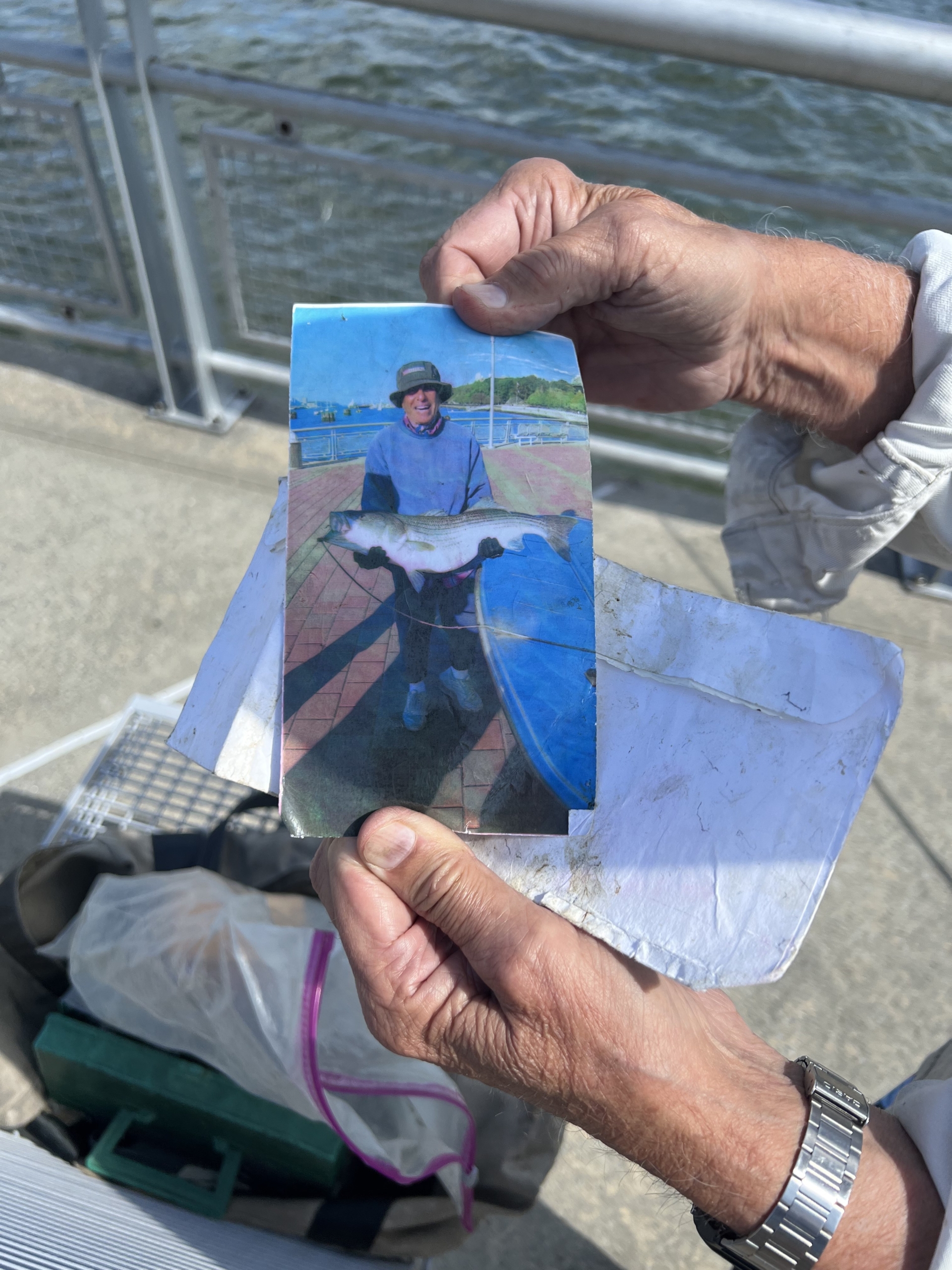

This was Pier I (as in the letter “i”), part of Riverside Park’s southerly extension, which had opened earlier in the year on land formerly occupied by unused freight rail yards. Zimmerman, an actor now in his 70s who formerly worked in advertising, grew up fishing in Michigan. Once he found Pier I, at the foot of West 70th Street, he visited nearly every weekend with rod and reel, and has been doing so ever since.

Luis Concepcion spotted Pier I from a very different angle. He was working construction on the roof of a building on the West Side a few years ago and saw the pier down below. He came with his gear the next weekend and caught nothing. But the following weekend, he says he landed a 48-inch striped bass, and, like Zimmerman, he, too, was hooked. “Biggest fish I ever caught in my life there. I’m the King of the Dock!” he says.

Zimmerman and Concepcion are part of a small but dedicated cadre of fishermen who drop their lines off the pier on a regular basis. According to Zimmerman (and to WSR reporting), many of the regulars appear to be immigrants with limited English proficiency. But even when he can’t strike up a conversation, Zimmerman often shares his catch with them. He is careful to identify himself as an “angler,” a fisherman who uses rod and reel rather than a net or trap. “All anglers are fishermen, but not all fishermen are anglers,” he explains.

But there are other regulars as well. West Side Rag reporter Joy Bergmann spoke with three of them back in 2019. Another is known as the Reverend, who sometimes sports a colorful sombrero. For a while last summer, the Reverend could be seen fishing from a small inflatable raft tethered to the pier’s pilings. But he gave that up – too bumpy with the wakes from passing boats, he told WSR.

Pier I extends about 700 feet into the Hudson River from the foot of West 70th Street. At that point, you are about a fifth of the way across the river to New Jersey. The next publicly accessible pier that extends this far into the river to the south is all the way down at West 44th Street, where boat traffic is much heavier. To the north, you would need to be on a boat to get this far from the Manhattan shoreline.

The pier also provides access to the water from both uptown and downtown sides, Zimmerman notes, allowing anglers to fish from the uptown side when the tide is coming in and the river is flowing north, and from the downtown side when the tide ebbs and the river flows south. That helps them avoid snags, which can occur when the line gets carried under the structure. Unlike some piers further south, Zimmerman adds, the fencing is built right up at the edge of the pier, allowing fish to be brought up easily. With nautical charts showing about 10 feet of depth at low tide off the end of the pier, there is plenty of cool water for big fish. It is not hard to see the attraction for anglers.

Thomas Balsley, a principal of the firm SWA/Balsley who designed and built Riverside Park South, which runs from West 59th Street north to 72nd Street, told WSR that fishing was always part of the design concept for the pier, going back to the original plans drawn up in 1991. “Obviously, it’s a multi-purpose pier,” he says, “and it wasn’t just intended for fishing, but we wanted to make sure that the fishermen were accommodated and that there were signals and messages that were sent in the design of it that said, ‘Hey, come out here and, you know, enjoy yourselves.’”

The original design of the pier included a fish-shaped table with running water for cleaning fish, but park goers recall there were issues with the water supply and the table was removed some years ago. According to Balsley, the scalloped shape of the south side of the pier was also designed with fishing in mind, providing bays for individual anglers to work from.

Longtime Upper West Siders may remember a time before this section of park existed. If you walked south past the 72nd Street baseball field as recently as the early 1990s, you came to a chain link fence, which could be peeled back, revealing acres of tall grass and rotting piers. There were fishermen perched among the pilings even back then.

The rail yards that used to occupy this area were abandoned by the 1980s, and the old Pier I had pretty much disintegrated by the 1990s. But at one time it had been a massive structure, wide enough to accommodate four parallel railroad tracks. According to a blog article by Thomas Flagg, a railroad historian who formerly gave walking tours of Riverside Park South, the original Pier I “handled bulk freight, heavy articles, and lumber, using hoisting apparatus on the barges, or ‘stick boats,’ or floating cranes tied up ot the pier, that loaded the freight onto open lighters [i.e., barges].”

The new Pier I was rebuilt along the foundations of the old structure, though not to the same width as the original and minus the railroad tracks. The fact that a pier had previously existed at that spot was critical in being allowed to build the new structure from an environmental regulation standpoint, since new construction covering the water is strictly limited. “We could have never built the pier if there hadn’t been one there already,” says Balsley.

Angler Zimmerman says people who see him fishing usually have two questions: “what do you catch, and can you eat them?”

The primary target of most anglers on Pier I is the striped bass. These beautiful fish can grow as long as five feet and live for years, leaving and returning to the river periodically to follow food and spawn. The minimum length for a “keeper” has long been 28 inches, but New York State this year has also put a cap on the maximum length, at 31 inches, for fish caught in the Hudson south of the George Washington Bridge. The goal is to help protect the breeding females, so “keepers” caught from Pier I must now be between 28 and 31 inches.

While striped bass may be the goal for most Pier I fishermen, Luis Concepcion recently landed a catfish on the pier, a species Zimmerman says he has been seeing down here for the first time this year. Summer flounder also can be found, and Concepcion says he has also pulled up sand sharks and eels, which he releases after showing any kids nearby. “They’re fascinated, taking pictures and everything, and then I just take them off the hook and throw them back in,” he says.

In the summer, some of the Pier I crew drop cage traps baited with chicken and bring up blue crabs. Rarely seen are the true giants of the river, the Atlantic sturgeon, which are protected by the Federal Endangered Species Act and cannot be legally caught, but occasionally are found dead and floating.

As for the second question, “can you eat them,” the answer is more complicated. Zimmerman is strictly a sport fisherman and doesn’t even really like to eat fish, he says. If he catches a keeper, though, he may hand it off to one of the other pier regulars, some of whom are likely using the river as a source of nutrition for their families or passing the fish along to others who eat them. Zimmerman believes the river is probably much cleaner than most people think. “I don’t like it when people say bad things about the Hudson,” he says.

Nonetheless, the New York State Department of Health does have guidelines for what is safe to eat due to accumulation of PCBs and, in the crabs, cadmium, a legacy of historic pollution by factories along the river. According to the department, adult males can safely eat up to one meal a month of striped bass from the Hudson, and can eat the meat (not the green stuff!) of the blue crabs up to four times per month. But the state recommends that “people who may bear children” under age 50 and children under age 15 not eat fish from the river at all. Catfish and eels are in the “don’t eat” category for everyone.

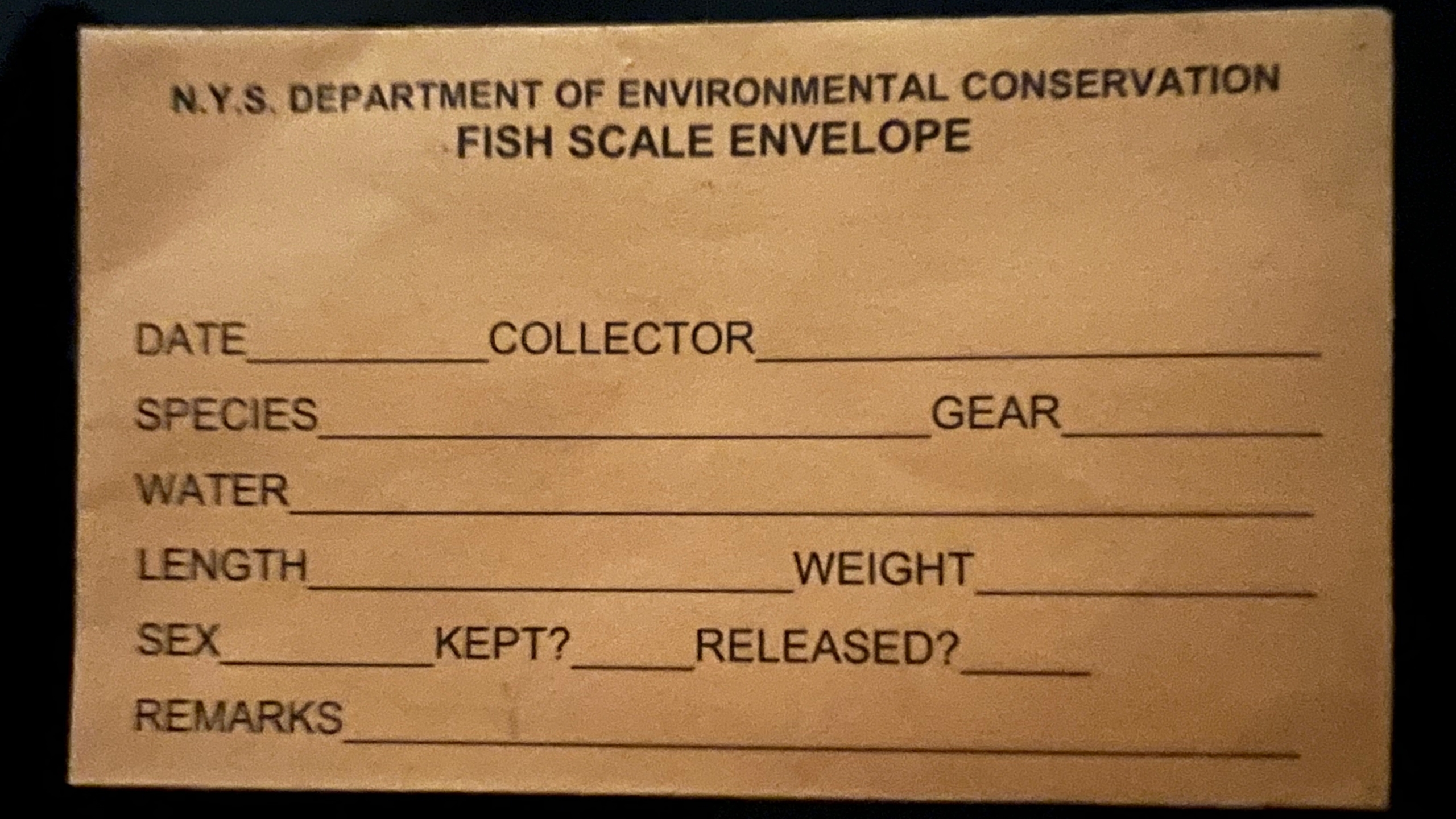

Anglers are an important source of information for the state Department of Environmental Conservation on the health of the fish population. When Zimmerman catches a striped bass, even one he is throwing back, he shaves off a scale with a small knife and sends it to the agency in a small brown envelope marked with information on where and when he caught the fish. At the beginning of the next spring, the department sends back a report with some information on the fish gleaned from the scale, such as its age, and the cycle starts again.

If you come down any day of the week you may find some of the regulars reeling in fish. Bring your own gear and give it a try, there is plenty of room on the dock.

Great,very informative article

Thanks

Thank you for this. I love learning about what I see happening in the neighborhood.

And I remember peeling back that chain link fence a million years ago…

such a cruel practice

I love eating fish. Sorry. Not giving it up because someone whines on social media.

Are you a vegetarian? As John E. said, caught and legally kept striped bass never go to waste and are an important source of protein though mind the consumption limits caused by industrial production, e.g. batteries.

Cruel? Not when you donate the fish to someone on the pier who can’t afford to buy it at Citarella or helping to ensure a healthy fish population. Anglers do more to protect clean waters than people who do nothing but complain about the sport of fishing.

If you ventured past the fence at 72nd Street, first thing you saw was a low structure with a sign announcing it as the “Railroad YMCA,” offering railroad workers some recreational facilities. There must be some stories to dig up…

So interesting! Great story.

Daniel, thanks for answering so many questions about the guys fishing off Pier 1. Nice job turning casual curiosity into a substantive piece of reportage.