By Wendy Blake

Elizabeth How lived in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692. She was one of 19 people, mostly women, executed amid the mass hysteria that we know as the Salem witch trials. Her story is part of a new exhibition at the New-York Historical Society that takes a new look – just in time for All Hallow’s Eve – at the forces that incited the witch hunt and the poignant stories of some of its targets.

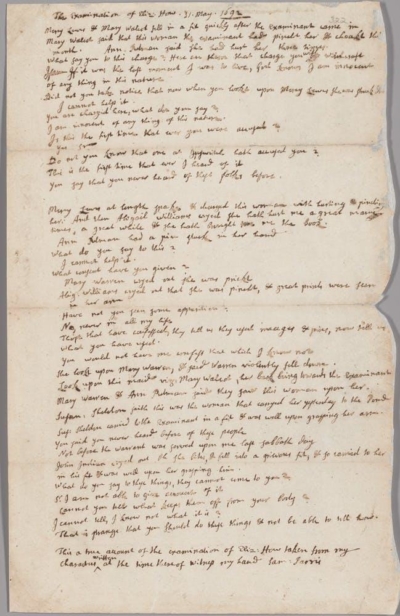

In the case of How, documents that tell her story include the handwritten condemnations of her accusers, including one from her own brother, charging her with bewitching his sow—it “leaped up about thre o fouer foot hie and turned about and gaue one squeake and fell downe daed.” Other neighbors’ letters testify to the good character of “Goodwife How,” one saying that she even pitied and prayed for her tormentors. In an examination of How (sometimes written as Howe), two teenage accusers said she made them feel as if they were being pricked by pins and pinched. She responded, “If it was the last moment I was to live, God knows I am innocent of any thing in this nature.”

The compact exhibition, “The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming,” aims to contextualize the mass hysteria that led to more than 200 people, including a 4-year-old, being accused of witchcraft in 1692-93. Historians disagree about the causes, but the exhibition suggests that events in the community and across the colony may have helped set the stage for the hysteria: a smallpox epidemic, extreme weather, and battles with the French and French-allied indigenous people. Long-standing feuds between neighbors, including disputes over property, also had led to rifts among the Salemites; as the mass delusion grew, some seized the opportunity to condemn their neighbors with false accusations.

“It is both a story of Salem 1692, a defining example of injustice in American history, and what happened to people who were impacted by the witch trials,” says Anna Danziger Halperin, associate director of the Center for Women’s History at the NYHS, which coordinated the exhibition with its original organizers at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem (the documents in this show are reproductions). “It’s about how we tell that story and what kind of meaning we take away from telling the story. It also prompts us to look inward at ourselves and look at, in moments of injustice, what position we would take.”

The New York venue added a section to the Peabody Essex show on Tituba, an indigenous woman from Barbados who was enslaved in the Salem home of the Rev. Samuel Parris and was one of the first to be accused of witchcraft, by Parris’s daughter and niece. Girls in the community had been experimenting with “folk practices,” like dropping eggs on mirrors—Halperin says these traditions were “likely Celtic or otherwise Pagan traditions that settler communities brought over from England.” The exhibition says there is no evidence that Tituba was involved in the original rituals. Parris’s daughter and niece started having “fits”—possibly caused by their fears of participating in these non-Christian rituals, and asked Tituba to prepare a “witch cake” to identify the perpetrators; they then denounced Tituba—who, like many of the accused, was a person at the margins of society.

Tituba is often vilified because she did “confess” to acts of sorcery, including riding a pole through the air, but this admission was actually a survival tactic, says Ms. Halperin. Somehow, Tituba’s life was spared; the indictment said there wasn’t enough evidence to convict her. (Many of the documents, along with transcriptions, can be viewed here .

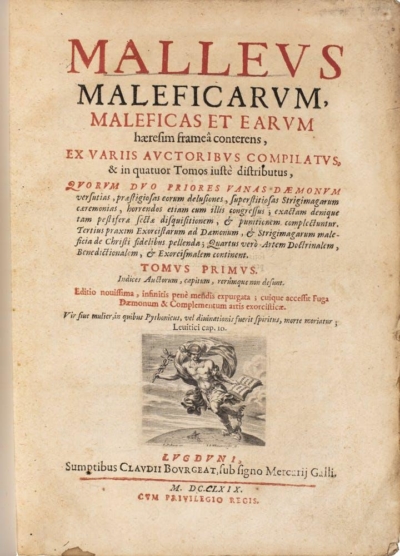

Also on view is a 1669 edition of a book written almost two centuries earlier by a European inquisitor. The book, Malleus Maleficarum, which would have been in circulation at the time of the trials, is one of the rare items that was contributed by the New York museum. It includes instructions on how to suss out witches; prescribes torture to induce confessions; and says poor, unmarried, elderly women pose great threats to Christian society.

Objects that belonged to some of the accused, such as an elegant sundial owned by John Proctor—who was hanged, along with his wife—bring these unfortunate citizens to life. A simple cane recalls gruesome charges leveled against a farmer, George Jacobs Sr., who required two canes to walk. During his trial, several girls claimed that an apparition of Jacobs (not Jacobs himself) had battered them with the canes.

From the “In Memory of Elizabeth Howe, Salem, 1692” collection

Velvet and satin

Gift of Anonymous donors in London who are friends of the Peabody Essex Museum, 2011

Peabody Essex Museum, 2011.44.1

One room in the exhibition is devoted to late fashion designer Alexander McQueen’s re-imagined costumes for witches. McQueen was inspired to stage a show of “witch” designs when he discovered that Elizabeth How was one of his ancestors. The museum calls it a “reclamation project”—an effort to redefine the word “witch” as a positive for women, a manifestation of their agency and power. On display here is a stunning, form-fitting black beaded dress he created—McQueen’s ensembles included headpieces in the shape of giant crystal moons and suns, summoning up Pagan nature symbolism. In the same room is the series of documents that tell the horrific story leading up to How’s execution.

The show features another artistic project aimed at redeeming the idea of “witch.” When New York photographer Frances Denny found she was descended from an accused witch as well as from one of the Salem trial judges, she was moved to make portraits of modern practitioners, including several from New York City. Karen Rose, who describes herself as the granddaughter of medicine people, speaks to the importance of Black healing traditions, which are often sidelined. Melissa Madara calls herself a “kitchen witch,” who sees the divine in mundane things. Others in the portrait gallery link their sense of personal and political power or genderqueer identity with their “witchhood.”

A guest book at the end of the exhibition, which asks visitors to describe how they would respond to a similar situation today, provokes some fascinating responses. One young visitor, Hazel, writes “I wod rily be mad becuas the prsin wod be inasit and I wod fite agenst it. I wod do any thig I cod to help.” Hazel writes that she is a descendant of Susannah Martin, who was hanged in Salem.

“The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming” will be on view until Jan. 22, 2023. The museum is holding several events related to the show, including family programs, such as a “historical Hallowe’en” on Oct. 30 from 4-6pm. Visitors of all ages are encouraged to come in costume and explore the exhibition.

Re: “I wod rily be mad becuas the prsin wod be inasit and I wod fite agenst it. I wod do any thig I cod to help.”

Ummm…Hazel, I think we’ve met! Weren’t you in one of my more hopeless Freshman English classes?

Then again, probably not; ’cause Witches do cast spells and you can definitely NOT spell.

Orrr… you are VERY clever, quick-witted, and able to emulate the English of four centuries ago.

For that an A+

Judging from her handwriting, Hazel was probably about 5 years old. Children—another group that’s misunderstood. 🙂

This write-up is better than the exhibit, which was full of egregiously ahistorical conjecture, 2022-style interpretations of past behavior, and then a portrait series featuring photos of random modern witches and select quotations on witchcraft . . . some of which were absolutely eye-rolling and delivered to the public with zero critical thinking . . . strange, considering that a lack of critical thinking and intellectual honesty is also at the heart of the witch trials . . .

It’s too bad that everything historical today gets looked at only from the perspective of the present. But there are quite a few very interesting genuinely historical books on the subject easily found. And there’s also Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, though I don’t consider it one of his better plays yet it’s still an effective indictment of witch-hunts like McCarthyism.

Well put!

It’s called “presentism”, a phrase brilliantly coined by Bill Maher, that perfectly describes the lunacy of projecting todays mores &values on the past.

Thankfully, 330 years later, America no longer suffers from such horrific mass delusions….

Makes me think of Brittney Griner.

I’m from this part of the country originally and a practicing witch. I appreciate that you’re trying to show witches in a more positive light but I don’t think you’re going about it the right way. The article doesn’t have enough information about the truth of witchcraft and just continues to spread misinformation. Please give people who aren’t able to attend the exhibit, more information.

Are you my ex-wife?

This is meant to just be a recap of the exhibition.