By Wendy Blake

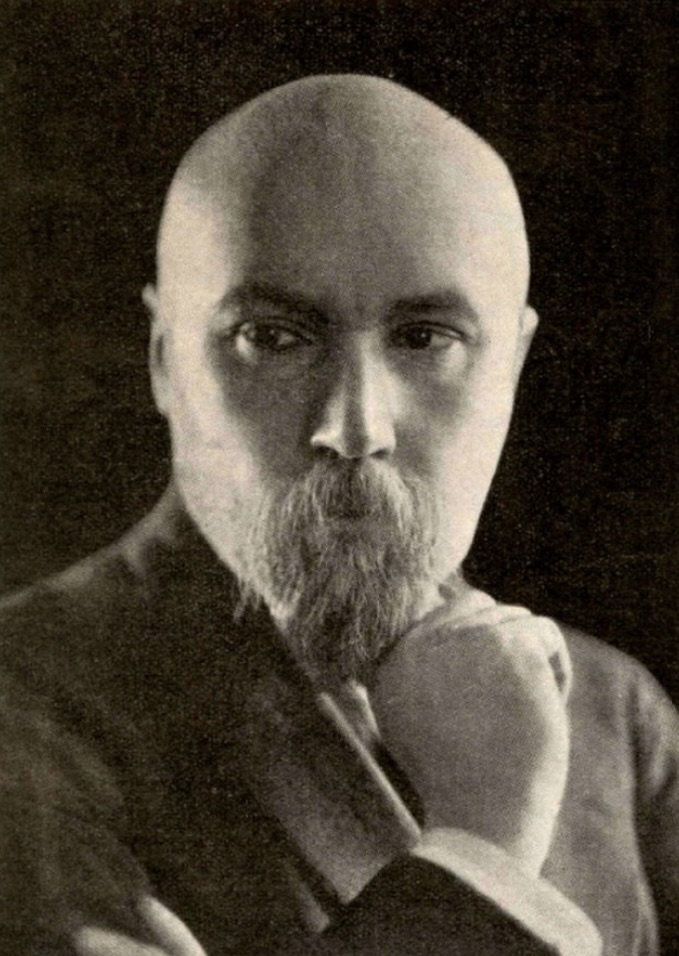

The uninitiated would never guess that the unassuming townhouse on West 107th Street, marked by a white banner bearing three mysterious red circles, is a museum dedicated to a charismatic Russian-born artist, mystic, archaeologist and savant who traveled in some of the highest circles of power in the first half of the 20th century. Nicholas Roerich was not only a prolific painter but also the originator of an international pact to protect global cultural treasures, the “guru” of a U.S. cabinet member, the would-be leader of a utopian Asian kingdom and, by some accounts, a spy.

“Roerich was the Indiana Jones of his time,” said Roerich biographer Oleg Shishkin in an interview with WSR. “His life was tied up with “mysticism, the liberation movement in India, the Communist International and the New Deal.”

Some 200 of his 4,000-plus artworks are on display at the Nicholas Roerich Museum, ranging from avant-garde set designs to luminous paintings of the Himalayas. There are artifacts from his expeditions to India and Central Asia, photos documenting his adventures and achievements, and engaging ephemera, such as a caricature from the 1920s depicting him rubbing shoulders with the likes of John Barrymore, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Charlie Chaplin.

“Our mission is to make available to the public the full range of Roerich’s accomplishments, which cover the realms of art, science, spirituality, peacemaking and more,” said Gvido Trepsa, museum director.

Roerich, born in 1874 in St. Petersburg, first found fame with the prestigious Ballet Russes. The museum displays some of his set designs for Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the shockingly experimental ballet that incited riots after its 1913 premiere. Much of his later work reflects the spiritual interests he cultivated after meeting his wife, Helena, a follower of theosophy, which draws from Hinduism and Buddhism (think turn-of-the-20th-century New Age). That influence can be felt upon entering the foyer, where one is met by scores of Buddhist figurines.

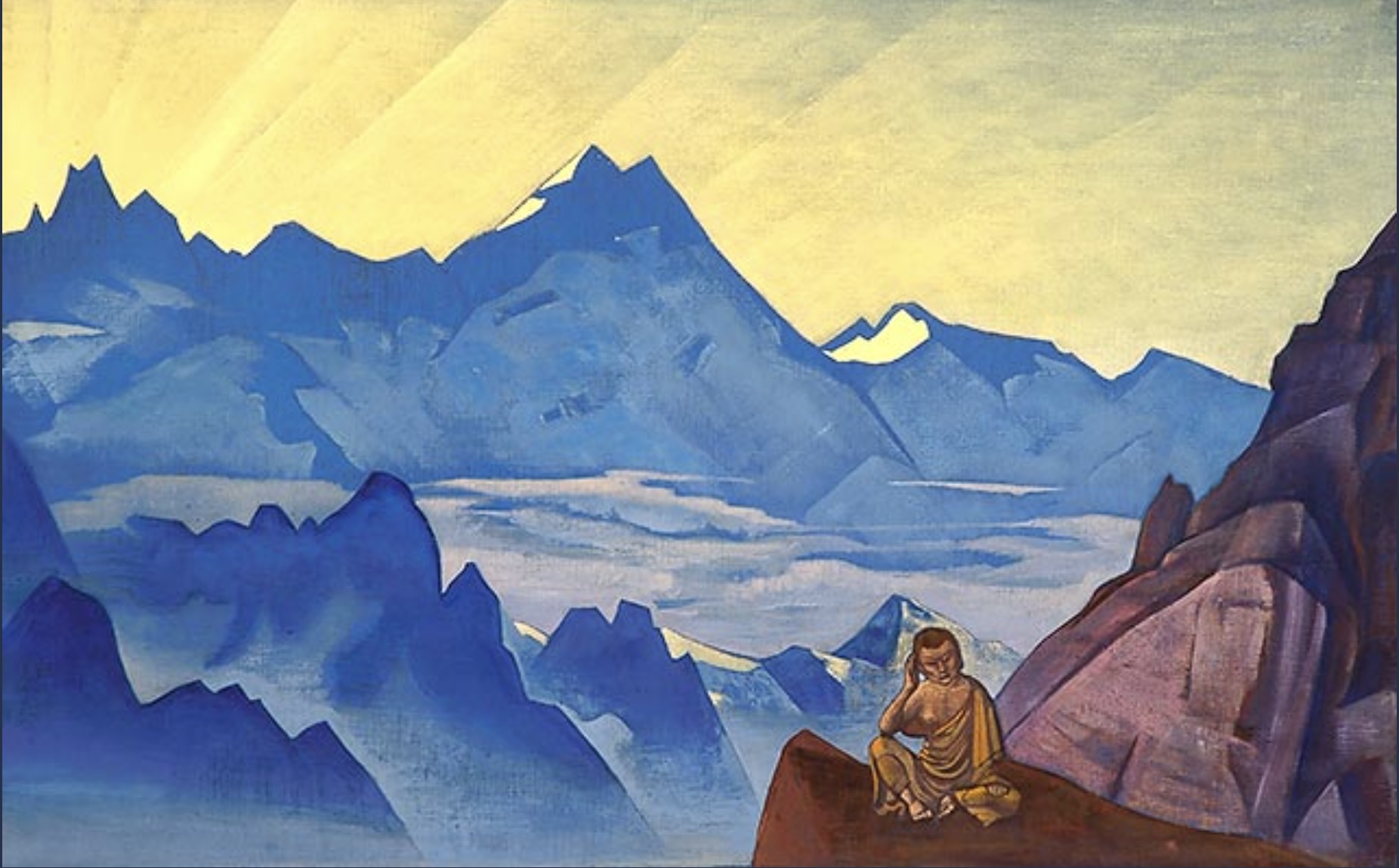

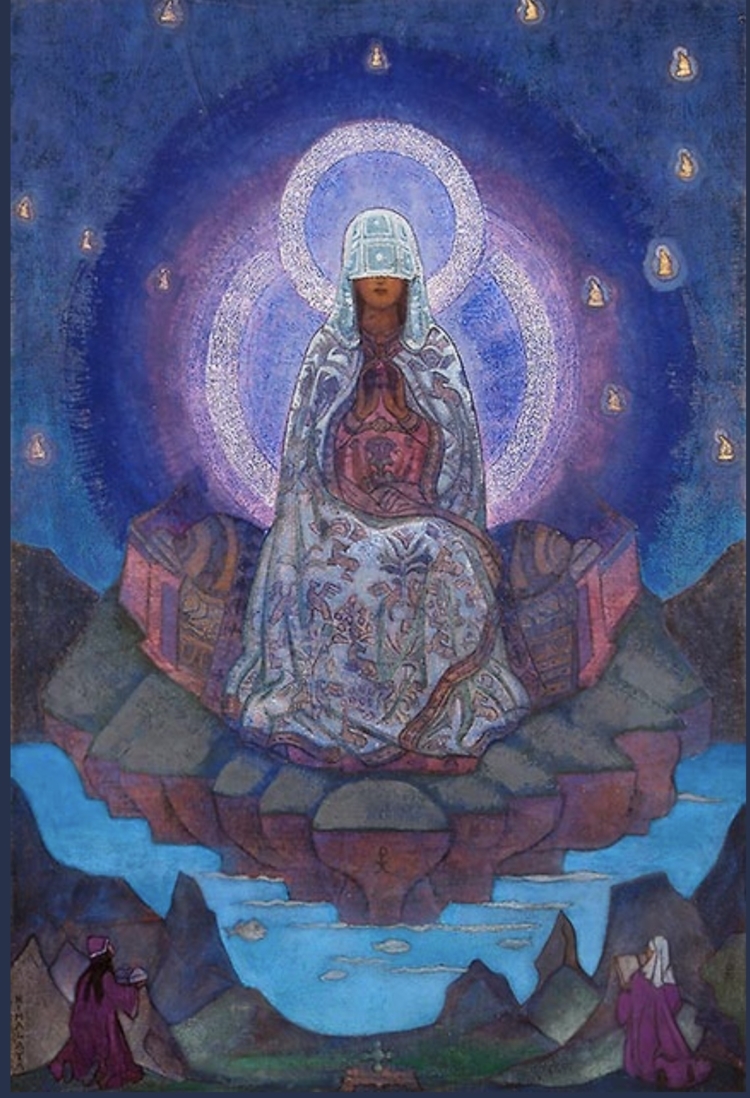

Roerich’s best-known works come out of his time in India and Central Asia. He and Helena were obsessed with finding the fabled Buddhist paradise of Shambhala—known as Shangri-La in the movie Lost Horizon. His dreamlike paintings of the craggy Himalayan mountains, many rendered in lush shades of blue tempera, often include yogis and other spiritual seekers as well as specific figures such as Krishna and Jesus. In the trippy painting “Mother of the World,” a veiled goddess is the center of a universe populated by Buddhas in tiny bubbles.

This eclecticism reflects the themes of Agni Yoga, an occult doctrine “channeled” by the Roerichs that aimed to syncretize all religions and bring about universal brotherhood. They claimed the teachings were telepathically transmitted to them by highly evolved Tibetans called the “Masters of the Ancient Wisdom.” The museum gift shop sells Agni Yoga treatises, which contain such revelations as, “When the superiority of the densified astral body has been recognized, then will the locks of the fourth Gates fall away.”

Roerich said he was destined, according to one of his Masters, to become the fifth Dalai Lama and founder of a kingdom uniting the lands of Central Asia. This “Sacred Union of the East” would be based on cooperative labor, said history professor and Roerich scholar Andrei Znamenski in an interview with WSR. Znamenski, who teaches at the University of Memphis, is the author of “Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia.” Roerich’s ideas, though esoteric, “were very much in line with the utopian idealism of the postwar world,” he said.

Those ideas apparently mesmerized some of America’s most influential people when Nicholas and Helena arrived in New York in 1920 (they left Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution). Roerich persuaded financier Louis Horch to back a five-year expedition of discovery to India, Mongolia, Tibet, and Siberia. While he did make archaeological finds, he was mainly focused on creating his utopian realm, calling up Mongol-Tibetan prophecies to rally supporters. At one point he sought help from the Bolsheviks (they refused), sparking speculation that he was a Soviet spy.

Back in New York, Horch built an Art Deco skyscraper at 103rd Street and Riverside Drive for the Roerichs’ Master Institute of United Arts. Completed in 1929, it offered art classes, displayed Roerich’s art and included artists’ apartments and a theater. (It is now the Master Apartments).

Henry Wallace, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s agriculture secretary and later vice president, was also fascinated by Roerich, even addressing him in letters as “Dear Guru.” Wallace advocated for a treaty proposed by Roerich that would safeguard countries’ historic sites during wartime. (The white banner, whose red circles represent art, science and religion, would fly over important institutions and monuments.) The “Roerich Pact,” signed by Roosevelt and 20 Latin American leaders in 1935, was a precursor to contemporary cultural protection conventions.

However, Roerich’s more eccentric pursuits led to a notorious scandal. In 1934, Wallace sent the artist and two botanists to Manchuria and Mongolia to find drought-resistant grasses that could be used to prevent future Dust Bowls. Once in Asia, though, Roerich abandoned the project to gin up support for his messianic kingdom. Along the way, he committed serious diplomatic blunders that disgraced Wallace, who shut down the project and had Roerich investigated for tax evasion.

Meanwhile, Horch sued the artist for $200,000 in unpaid loans. The Roerichs left the U.S. under a pall and settled in India’s Kullu Valley, sandwiched between the Himalayas, where they spent the rest of their lives. There, they received such prominent figures as Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister. Roerich’s artwork is considered a national treasure in India and, as such, cannot be exported.

Roerich died in 1947. Two years later, several American supporters, including close family friend Katherine Campbell-Stibbe, bought the 107th Street townhouse and established a trust to maintain it. Most of the artwork was donated by the museum’s founders and Roerich’s son Svetoslav.

“Roerich is still considered a guru by more than 100,000 followers worldwide,” according to Trepsa. But some are betraying Roerich’s legacy with their “we-are-the-chosen people nationalism,” according to notes of the Agni Yoga Society, also based in the 107th Street building. The notes say “pro-Putin and pro-war so-called Roerichites,” mostly in Russia, “bear full responsibility for war crimes being committed in Ukraine.” The museum itself has posted a 1939 anti-war essay by Roerich on its home page, but a Ukrainian flag on the first floor makes a stronger statement.

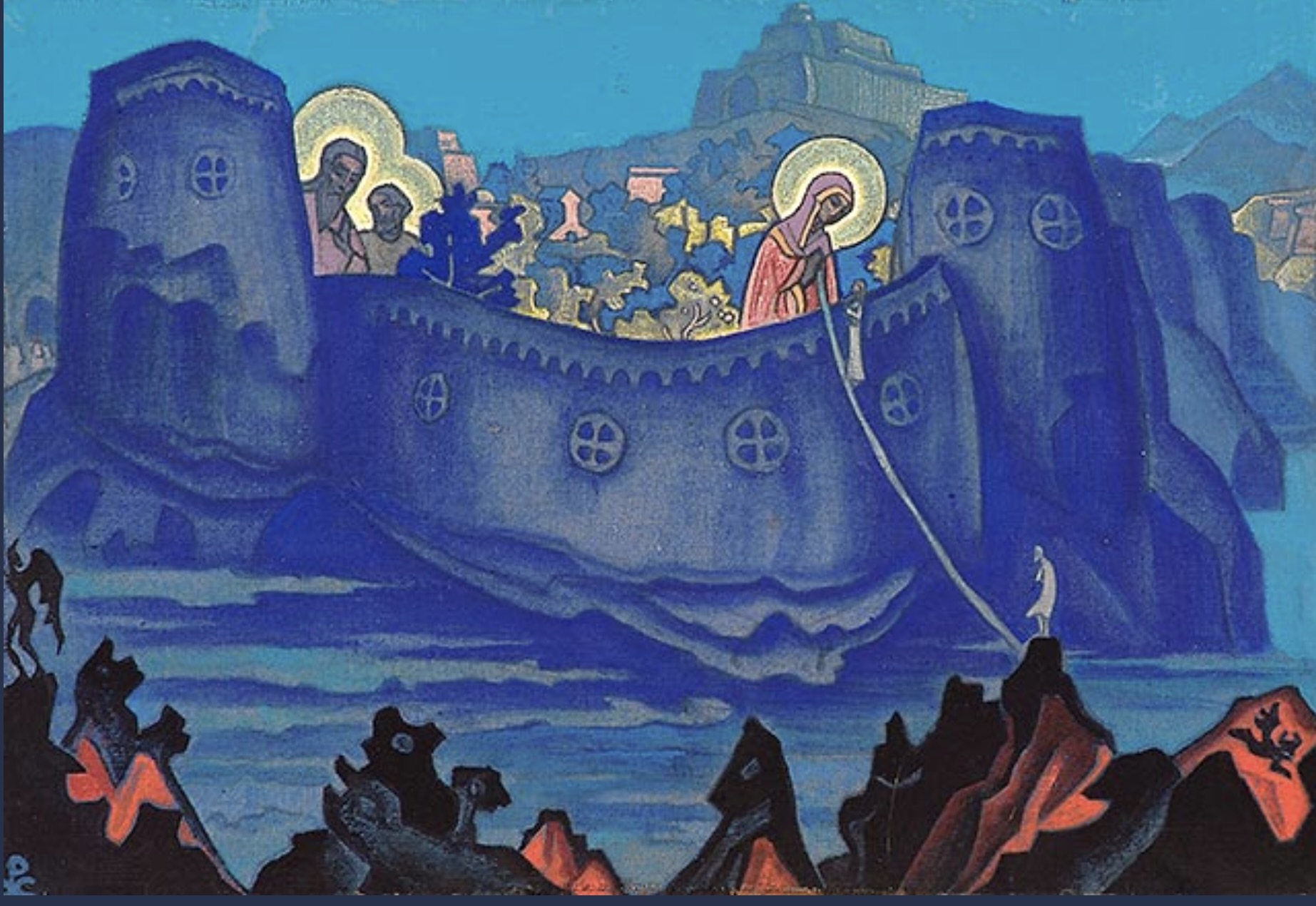

Though Roerich’s work has been largely ignored by Western art historians, it is in demand in Russia, especially as Vladimir Putin emphasizes Russia’s heroic past. “Madonna Laboris,” a painting in which the Virgin Mary helps souls ascend to a heavenly citadel, sold for $12 million in 2013, a record at the time for Russian art auctions (the museum has a version). It’s rumored that the price was inflated by two oligarchs in a bidding war, both intending it as a present for Putin.

Nicholas Roerich Museum, 319 W. 107th St. Admission is free. Tuesday–Friday, noon–4 p.m., Saturday and Sunday, noon–5 p.m.

To receive WSR’s free email newsletter, click here.

I love this little gem of a museum.

I used to take piano lessons at the original Roerich Museum/Masters Institute in 1934-35, walking there from my home at 800 West End Ave. My teacher was also an emigre from Russia.

That’s amazing, Eileen! Thank you for sharing that!!

Fascinating note from the 1930s, Eileen! It sounds like there were quite a few financial woes and rearrangements at the Inststitute/Masters Building that decade. Do you have any recollection of the “Riverside Museum” that reportedly existed there and exhibited modern artists before World War II?

Thanks so much for this, Wendy and WSR.

I wandered into that little museum years ago, but had no clue about the fascinating backstory. So many treasures in our UWS backyard…

Incredible well researched piece !

I had no idea about this museum – or this guru/fellow either. So interesting that the museum is his former home. Adding this to my must-visit list. Thanks.

What an amazing story! Thanks for spotlighting this gem in our backyard

Trippy for sure

World spanning article. Enjoyed reading.

Great article. Fun fact – the 103rd and Riverside building still has a visible connection to Roerich. Look at the cornerstone (at the corner of 103rd and Riverside) and you’ll see the Roerich logo with the three circles.

I’ve been to this little museum many times over the years, but not for a while now.; thanks for the reminder! I have bought prints of some of the paintings. It’s a peaceful, inspirational place.

He was instrumental in the construction of the Master’s Apartment Building at 310 Riverside Drive just down the street from the museum. Some of his work is still visible in the lobby floors. Art shows are still held i the lobby area by the main entrance. It’s a fascinating place.

Amazing! Thank you!

Wonderful place.Prior to Covid attended their musical performances on top floor. Would be nice if those concerts started up again.

Yes, been there many times, including their afternoon classical music concerts. I didn’t know they never resumed after pandemic. Time to revisit the museum. Wonderful article. Thank you for reminder about this neighborhood treasure.

For fans of horror fiction, Roerich has a special significance: He may well be the only painter ever referred to by name in the tales of H. P. Lovecraft, who, in his great Antarctic novella “At the Mountains of Madness,” compares the weird polar landscape to Roerich’s artwork. (There are a number of sites online that discuss this connection.)

Great article, Wendy! Thanks so much for bringing this museum (and this person) to my attention. I can’t wait to go there.