By Anya Schiffrin

As I left the I’ll Have What She’s Having exhibit recently, a tribute to the city’s Jewish delis at the New-York Historical Society (W. 77th and CPW), my eye caught a familiar figure from a very different era of New York history.

It was Clyde Miller, who makes a fleeting appearance on one of the museum’s video panels (near the lobby restrooms), highlighting Time magazine’s coverage of racism in the 1930s.

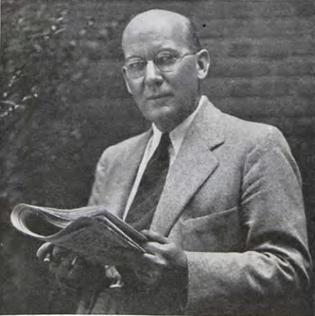

Miller was a powerful advocate for racial tolerance, and for using “media literacy” to combat hate speech and propaganda. His work at Columbia University Teachers College some 80 years ago made the Upper West Side the epicenter of that era’s battle against disinformation. Although he was let go by Teachers College in the 1940s, his ideas formed the bedrock of much of today’s media literacy education in the United States.

In Miller’s time, the enemy of truth was propaganda. Today, we call it misinformation or disinformation, in all its many forms — deep fakes, conspiracy theories, and yes, propaganda. And today, major news outlets and social media platforms have fact-checking staffs and standards editors. But in the 1930s, there was only Clyde Miller, his followers, and Teachers College, the Upper West Side institution that, for just a few years, gave him and his work a safe haven.

The 1930s were a time of tremendous worry about propaganda. Many believed that the propaganda of the World War I era was more powerful than any that had preceded it, and in that postwar era, the rise of Nazi Germany and growing racism and antisemitism in America gave the problem a new urgency. Thirty million listeners tuned in to the weekly radio broadcasts of fiery, antisemitic priest Father Charles Coughlin. The Soviet Union had created an enormous apparatus of propaganda and state control of media.

All of this made for a hellscape of déjà vu for Miller, a former journalist who, like many others, raised the alarm about the effect propaganda was having on democracy. Department store magnate and philanthropist Edward Filene gave Miller $10,000 to fund a new Institute for Propaganda Analysis at Teachers College, which quickly focused on media literacy as a powerful antidote to propaganda.

Miller and the group of prominent sociologists working with him at the institute optimistically believed that reasoning and “scientific thought” would provide a counterweight to the growing menace of “dishonest” persuasion that they identified and analyzed. Their approach rejected both government regulation (runs counter to First Amendment free speech rights) and counter-messaging campaigns (viewed as fighting one form of propaganda with so-called “good” propaganda). Instead, the “American Way” of dealing with propaganda, as Miller was fond of calling it, was to promote critical thinking.

To do that, the institute published books and pamphlets for use in schools and created newsletters and discussion questions for teachers. Today there are many more media literacy efforts, built into school curricula or readily available for educators, but their fundamental approach is little changed from what Miller’s institute was doing 80 years ago.

Miller and his colleagues also were involved with a movement to develop an anti-racist curriculum for schools. He worked with a friendly superintendent on a curriculum for Springfield, Massachusetts (it’s that work of his that’s featured in the video at the New-York Historical Society). Detroit, New York, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles and other cities were also part of the movement.

But then came the backlash. Miller was deeply involved with the Methodist Federation for Social Action, a movement that fought social inequality and was critical of capitalism. In 1946, the World Telegram’s red-baiting columnist Frederick Woltman attended the Federation’s national meeting and wrote a column accusing the group of Communist sympathies. Miller protested by writing to Columbia Journalism School, demanding that it rescind Woltman’s Pulitzer Prize for reporting that year (the prize still stands).

Miller’s institute was also investigated by the Dies Committee, forerunner of the notorious, red-baiting House Committee on Un-American Activities. Teachers College put him on leave in 1943 and five years later officially terminated him. A letter I found in Columbia’s Central Archives while researching his work informed Miller that Teachers College “does not in the foreseeable future require the services of a person working in your special field of competence.” When he lost his job he also lost his Columbia apartment on 120th Street, and in a 1948 interview with The New York Times, he accused the university of violating his academic freedom. An effort to get Columbia to pay him $100,000 in damages appears to have failed.

Though the Red Scare led directly to Miller’s ouster, profound changes were underway at the same time that radically redefined communications academics. Scholars stopped talking about propaganda, instead referring to “communications research.” Focus groups and longitudinal panel studies replaced development of media literacy pamphlets. When the official history of Teachers College was published in 1954, Clyde Miller and the Institute for Propaganda Analysis were not even mentioned.

Miller remained in New York until 1971, when he moved to Australia where his son lived. He died and was buried there in 1977. When I met his granddaughter Andrea Packard last summer in Melbourne, she shared memories of visiting Miller on the UWS and touring the World’s Fair with him in the 1960s. Packard said she didn’t know much about her grandfather’s legacy. When I told her about his work she was pleasantly surprised to learn that Clyde Miller’s techniques in fighting for truth are very much alive today.

Thanks to Chloe Oldham and Eve Liberman for research help.

Anya Schiffrin has taught at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs for nearly 20 years and is the director of the school’s Technology, Media and Communications specialization.

This is utterly heartbreaking. Here’s hoping that Columbia treated the author better than they treated Miller. 😟

This is an excellent article and so timely. I am one of those who always believes education could fix the problems we have with disinformation in our society, but this story shows how it has its bounds. If only we could make critical thinking work.

An excellent piece of Investigative Journalism whose intent is to uncover the truth no matter how uncomfortable it makes us.

ANOTHER such work is the podcast “Ultra”, by MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, which reveals that, prior to Pearl Harbor’s causing the U.S. to enter WWII, a known agent of Nazi Germany worked with some 20 U.S. senators and congress-persons to both foster antisemitism and pro-Nazi propaganda to keep us out of that war.

Supposedly Stephen Spielberg (“Schindler’s List”) has optioned Ultra and may, hopefully, produce a film based on it.

I think this is the book that Maddow drew on: Hart, Bradley. Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States. NY, NY: Thomas Dunne Books, 2018

Yes and i think she read the same book I did on the topic. Will find and post a link. Thank you very much

Loved the Anya Schiffrin essay on the tragedy of Clyde Miller. Am sorry I didn’t know about him till just now.

Thanks for all you do, WSR. Dedicated reader before I left UWS after 30 years in the nabe. Now in Midtown East and only check in occasionally.

All good wishes always.

Excellent and informative essay—thank you! Those who cannot remember—or learn from—the past are condemned to repeat it.

Wonderful article and bravo Clyde Miller! What a stalwart pioneer! Columbia should have a memorial to you or a prize in your name. What a wonderful human being!

Great piece! Thank you!!

This is the kind of thorough, well-produced news coverage that is unavailable to folks other than us West Siders, here in New York

Thank you very much. My researcher contacted ten different archives. Nice to know our efforts are appreciated