By Wendy Blake

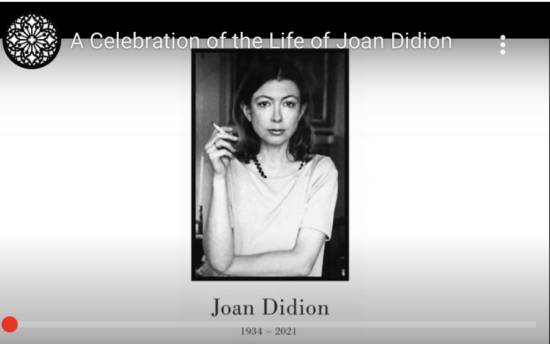

This week, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine became the cathedral of Joan Didion—the keen cultural observer whose writing has influenced generations—as friends and luminaries such as Vanessa Redgrave, Calvin Trillin and Hilton Als gathered Wednesday to celebrate her life.

Didion, a native Californian who described herself as “heterocoastal,” died in December 2021 at the age of 87. She’d lived on the Upper East Side in her 20s and came back to that neighborhood with her husband in 1988 (first trying out an apartment on West 58th Street but moving because it “wasn’t like a hotel room … It had to be taken care of”). She was a practitioner of the “New Journalism” of the 1960s and 1970s. Her nonfiction writings were novelistic, subjective and immersive. Didion, who once said she learned to write as a teenager by retyping lines from Hemingway, constructed sentences that were spare but powerful – like an “X-Acto knife,” said New Yorker editor David Remnick, one of more than a dozen speakers who sought to capture her style and her impact for an overflow audience.

Her watershed book, “Slouching toward Bethlehem,” a compilation of essays – including one in which she mixes with acid-dropping hippies – shatters the image of California’s utopian counterculture and indicts the dissolution of the 1960s. Her body of work includes novels, such as “Play It As It Lays”; screenplays, including one for “The Panic in Needle Park” in 1971, about heroin addicts in what is now Sherman Square in the West 70s; and a memoir of grief, “The Year of Magical Thinking,” published in 2005 after her husband, John Gregory Dunne, died, and her daughter, Quintana Roo, became ill (Quintana Roo died after the book was written).

Those who spoke described a writer committed to seeing the world clearly, one who distrusted narratives that make us comfortable. “Try not to be crippled by ideas; I’m talking about looking out, about looking out at the world and trying to see it straight,” she once told graduates at the University of California, Riverside. Former California Gov. Jerry Brown, who spoke on video, remembered that quote and Didion’s personal revelation to the graduates: that she had struggled all her life “against my own misapprehensions, my own false ideas, my own distorted perceptions. I’ve had to … make myself unhappy, give up ideas that made me comfortable, trying to apprehend social reality.”

Didion’s devotion to getting beyond conventional narratives led to a 1991 piece in the New York Review of Books on the “Central Park Five,” the first mainstream article to suggest that the teenagers accused of murdering a jogger in the park were wrongfully convicted. In it, she deconstructed the classist, racist storyline that led to their imprisonment. “She saw things plain as so many others have not,” said Remnick.

Each speaker reached deep to explain what Didion had meant to them, and to the American society she wrote for. Novelist Susanna Moore said she studied the author herself as she would a “rune of mysterious and magical significance.” After reading Moore’s first book, Didion said, “It’ll do…now write it again.” Another of her epigrammatic (and rarely offered) dicta: “Drop this whole idea of knowing the truth.”

New Yorker theater critic Hilton Als said Didion’s work held up a mirror to the culture. “We are all inheritors of a cracked, chaos-filled kingdom, one where the center does not hold,” he said, “but you can learn something from fracture if only you can face the cracks and fissures, which are the cracks and fissures of history.”

Jia Tolentino, another New Yorker writer, mourned the loss of a voice that could speak to the “dread and anomie of our present: the melting pavement, the taps running black in Jackson, Mississippi, the bodies washing up in Lake Mead, the undrinkable rainwater, the angry hordes at the Capitol, the sinkholes of conspiracy, the grief, the severance of reality, the performance of authority, the tankers breaking down in the Suez Canal … We want a Didion roadmap, a sentence that contains the country’s entire weather.”

Even in smaller moments, Didion offered eloquent insights. Moore recalled the night Bianca Jagger came to a dinner party at Didion’s home and spent the evening leafing through magazines. “I had rarely seen Joan so angry,” said Moore. After other guests left, “She turned to me and said, “Evil is the absence of seriousness – nothing more.”

A video of the event can be viewed below. (Sound starts at 20:15)

Thank you so much for this kind, affectionate tribute. We lost such a VITAL voice with Joan Didion’s death. Where do we find another of such honesty and decency?